Acne

vulgaris

Salient

features

·

Acne

vulgaris is a common disorder of the pilosebaceous unit.

·

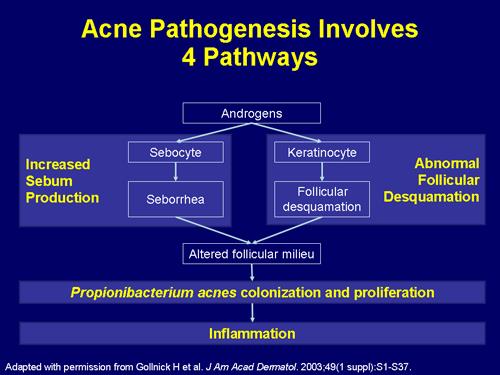

There

are four key elements of pathogenesis: (1) follicular epidermal

hyperproliferation, (2) sebum production, (3) the presence and activity

of Propionibacterium acnes, and (4) inflammation and immune

response.

·

Clinical

features include comedones, papules, pustules, and nodules on the face, chest,

and back.

·

Treatment

often includes combinations of oral and topical agents such as antimicrobials,

retinoids, and hormonal agents. Laser and light sources are additional

treatment options.

Introduction

Acne is a chronic

inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous units.

It is characterized by the formation of open

and closed comedones, erythematous papules and pustules and in more severe

cases nodules, deep pustules and pseudocysts. Seborrhoea along with scarring

and post‐inflammatory erythema and/or

pigment changes is common features. While the course of acne may be

self-limiting, the sequelae can be life long, with pitted or hypertrophic scar

formation.

The central pathophysiological feature of

acne is increased androgenic stimulation and/or end-organ sensitivity of

pilosebaceous units leading to sebum hypersecretion and infundibular hyperkeratinization.

These events lead to Propionibacterium acnes proliferation and subsequent

inflammation.

There are two types of 5 alfa reductase, type

1 and type 2. Type 1 is most relevant in acne because sebaceous glands in acne

prone regions show abnormally high 5alfa reductase type 1 activity which

supports the end organ hyper-responsive to androgen theory for acne.

Epidemiology, including

Genetic and Dietary Factors

Acne is a common disorder affecting the majority of

adolescents and often extends into adulthood. Globally,

acne accounts for ~0.3% of the total and ~16% of the dermatologic disease

burden. Acne often heralds the onset of puberty. With a peak incidence

during adolescence, acne affects approximately 85% of young people between 12

and 24 years of age and is therefore a physiologic

occurrence in this group. With the general trend over the past few decades for

earlier puberty, preadolescent acne affecting children 7 to 11 years of age has

also become more common. While typically thought of as a disease of youth, acne

often continues to be problematic well into adulthood. In a survey-based study it

has shown that, 35% of women and 20% of men reported having acne in their 30s,

while 26% of women and 12% of men were still affected in their 40s.

The disease may be

minor, with only a few comedones or papules, or it may occur as the highly

inflammatory and diffusely scarring acne conglobata. The most severe forms of acne

occur more frequently in males, but the disease tends to be more persistent in

females, who may have periodic flare-ups before menstrual periods, which

continue until menopause.

Individuals

at increased risk for the development of acne include those with an XYY

karyotype or endocrine disorders such as polycystic ovarian syndrome,

hyperandrogenism, hypercortisolism, and precocious puberty. Patients with these

conditions tend to have more severe acne that is less responsive to standard

therapy.

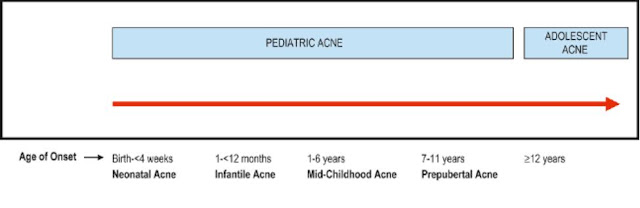

Pediatric acne is the

terminology applied to acne occurring from birth through 11 years of age; adolescent

acne describes patients from age 12 to adulthood.

Genetic Factors

The

precise role of genetic predisposition in the multifactorial pathogenesis of

acne remains to be determined. The number, size, and activity of sebaceous

glands is inherited. It is a widely belief that the tendency to have

substantial acne (including the nodular variant) runs in families, and an

association between moderate to severe acne and a family history of acne has

been observed in several studies.

Dietary Factors

The

relationship between diet and acne remains a subject of controversy. Several

observational studies in different ethnic groups have found that intake of

milk, especially skim milk, is positively associated with acne prevalence and

severity. Exacerbation of acne with the use of whey protein supplements for

body building has also been reported. In addition, prospective studies have

documented a link between a high glycemic-load diet and acne risk. A recent

investigation found that vitamin B12 supplementation

can potentially trigger the development of acne by altering the transcriptome

of skin microbiota, leading to increased production of proinflammatory porphyrins

by Propionibacterium acnes.

Pathogenesis

Factors

causing acne

The classical concept is that acne results from the

combination of increased sebaceous gland activity with hyperseborrhoea,

abnormal follicular differentiation with increased keratinization, microbial

hypercolonization of the follicular canal with P. acnes and increased

inflammation primarily through activation of the adaptive immune system. New

research results have led to a modification of this classical explanation as

more primary pathophysiological factors have been identified. Along with a

genetic predisposition, other major factors include androgens, pro‐inflammatory

lipids such as ligands of sebocyte peroxisome proliferator‐activated

receptors (PPAR) and other inflammatory pathways. In addition, neuroendocrine

regulatory mechanisms, diet and exogenous factors all may contribute to this

multifactorial process.

Inflammatory

cascades involved in acne pathogenesis.

The

development of acne involves the interplay of a variety of factors, including:

(1) follicular hyperkeratinization; (2) hormonal influences on sebum production

and composition; and (3) inflammation, in part mediated by P. acnes

Inflammatory

papule/pustule

·

Proliferation of P.

acne which up regulates innate immune response (e.g. via TLRs)

·

Mild perifollicular

inflammation (primarily neutrophils). Sebaceous lobule regression

Nodule

·

Marked perifollicular

inflammation (primarily T cells)

·

May lead to scarring

Follicular Hyperkeratinization

The microcomedo is thought to be the precursor of all

clinically apparent acne lesions. It forms in the upper portion of the follicle

within the lower portion of the infundibulum, the infrainfundibulum.

Corneocytes, which are normally shed into the lumen of the follicle and

extruded through the follicular ostium are retained

and accumulate due to increases in both follicular

keratinocyte proliferation and corneocyte cohesiveness, leading to the

development of a hyperkeratotic plug and a bottleneck phenomenon. The inciting

event for microcomedo formation is unknown, but data support a putative role

for interleukin-1α (IL-1α). Factors causing increased sebaceous

secretion (puberty, hormonal imbalances) influence the eventual size of the

follicular plug. The plug enlarges due to accumulation of shed keratin and

sebum behind a very small follicular orifice at the skin surface with no

obvious opening and becomes visible as a closed comedone. An open comedone

(blackhead) occurs if the dilated follicular orifice opens. Further increase in

the size of a blackhead continues to dilate the pore, but usually does not

result in inflammation. The closed comedone is the precursor of inflammatory

acne papules, pustules, and nodules.

Hormonal Influences on Sebum Production and Composition

The

sebaceous gland is controlled primarily by androgens, with additional

influences from other hormones and neuropeptides. Androgens are produced both

outside the pilosebaceous unit, mainly by the gonads and adrenal glands, and

locally within the sebaceous gland via the action of androgen-metabolizing

enzymes such as 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

(HSD), 17β-HSD and 5α-reductase.

Androgen receptors, found in the cells of the basal layer of the sebaceous

gland and the outer root sheath of the hair follicle, are responsive to

testosterone and 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT),

the most potent androgens. DHT has a 5–10-fold greater affinity than

testosterone for the androgen receptor and is thought to be the principal

androgen mediating sebum production.

A = androstenedione; ACTH = adrenocorticotropin-stimulating hormone; DHEAS = dehydroepiandrosteronesulfate; E = estrogen; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; LH = luteinizing hormone; T = testosterone; DOC = deoxycortisol.

Pathways of C19 steroid metabolism

Dehydroepiandrosterone

(DHEA) is a weak androgen that is converted to the more potent testosterone by

3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) and 17β-HSD in peripheral tissues like pilosebaceous

follicles. Finally, testosterone gets converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by

5α reductase before it binds androgen receptors in target tissues,

predominantly on the sebaceous gland. Both DHEA and testosterone can be

metabolized to estrogens by the enzyme aromatase. The sebaceous gland expresses

each of these enzymes.

The

impact of androgens on sebaceous gland activity begins during the neonatal

period. From birth until approximately 6–12 months of age, infant boys have

elevated levels of luteinizing hormone (LH), which stimulates testicular

production of testosterone. In addition, both male and female infants exhibit

increased levels of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA sulfate (DHEAS)

secondary to a large, androgen-producing “fetal zone” in the adrenal gland that

involutes during the first year of life. Of note, sebaceous gland activity in

infants is not due to persistent maternal hormonal stimulation, as was

previously hypothesized. Both testicular and adrenal androgen production

decrease substantially by 1 year of age and remain at a stable nadir until

adrenarche.

With

the onset of adrenarche, typically at 7–8 years of age, circulating levels of

DHEAS begin to rise due to its production by the adrenal gland. This hormone

can serve as a precursor for the synthesis of more potent androgens within the

sebaceous gland. The rise in serum levels of DHEAS in prepubescent children is

associated with an increase in sebum production and often the initial

development of comedonal acne. Although the overall composition of sebum is

similar in persons with or without acne, those with acne have variable degrees

of seborrhea and their sebum tends to have higher levels of squalene monounsaturated

fatty acids but less linoleic acid.

Little

is known about the physiologic role of estrogens in modulating sebum

production. Estrogen administered systemically in sufficient amounts decreases

sebum production, although the dose of estrogen needed is greater than the

dose required to suppress ovulation and increases the risk of thromboembolic

events. However, acne often responds to treatment with lower-dose oral

contraceptives containing 20–50 mcg of ethinylestradiol or its esters, because

suppression of ovulation itself inhibits ovarian androgen production.

Postulated mechanisms for estrogen-mediated downregulation of sebogenesis

include direct opposition of androgens within the sebaceous gland, a negative

feedback loop that decreases androgen production via inhibition of pituitary

gonadotropin release, and regulation of genes that affect sebaceous gland

activity.

Inflammation in Acne

It

is clear that when a follicle involved with acne ruptures, it exudes keratin,

sebum, P. acnes, and cellular debris into the surrounding

dermis, thereby significantly intensifying inflammation. However, inflammation

is also seen early in acne lesion formation. For example, in acne-prone sites,

the number of CD4+ T cells and levels of IL-1

have been shown to be increased perifollicularly prior to hyperkeratinization.

In addition, insulin-like growth factor-1 has been found to increase the

expression of inflammatory markers and sebum production in sebocytes.

The

type of inflammatory response determines the clinical lesion seen. If

neutrophils predominate (typical of early lesions), suppuration occurs and a

pustule is formed. Neutrophils also promote the inflammatory response by

releasing lysosomal enzymes and generating reactive oxygen species; levels of

the latter in the skin and plasma may correlate with acne severity. An influx

of lymphocytes (predominately T helper cells), foreign body-type giant cells,

and neutrophils results in inflamed papules and nodules. The type of

inflammatory response also plays a role in the development of scarring. Early,

nonspecific inflammation results in less scarring than does a delayed, specific

inflammatory response.

Propionibacterium acnes and the Innate

Immune System

P.

acnes is a Gram-positive, anaerobic/microaerophilic rod that is

found deep within the sebaceous follicle, often together with smaller numbers

of P. granulosum. In adults, P. acnes is the predominant organism in the

microbiome of the face and other sebaceous skin. P. acnes produce porphyrins (primarily

coproporphyrin III) that fluoresce with Wood’s lamp illumination.

For

the most part, P. acnes is considered to be a

commensal organism of the skin rather than a pathogen per se. Although studies have documented increased

levels of P. acnes on the facial skin of

acne patients, the P. acnes density

does not correlate with clinical severity. Because P. acnes is nearly ubiquitous yet not everyone has

acne, differences in the pathogenicity of particular P. acnes strains and variable host responses

to P. acnes have been postulated. In a comparison of

the microbiome of facial skin in individuals with and without acne, certain

ribotypes of P. acnes (types 4 and 5) are

more frequently found in acne patients, suggesting that these strains are

either more capable of inducing acne or better suited to survive in an acne

environment. However, another study showed that monocytes from the peripheral

blood of patients with acne exhibited more robust cytokine release in response

to P. acnes stimulation than did monocytes from

individuals without acne.

The pathogenicity of P. acnes includes the direct release of lipases,

chemotactic factors, and enzymes that contribute to comedo rupture, as well as

stimulation of inflammatory cells and keratinocytes to produce proinflammatory

mediators and reactive oxygen species. Lipases hydrolyze

sebum triglycerides to form free fatty acids, which are comedogenic and primary

irritants. Chemotactic factors attract neutrophils to the intact follicular

wall. Neutrophils elaborate hydrolases that weaken the wall. The wall thins,

becomes inflamed (red papule) and pustule, and ruptures, releasing part of the

comedone into the dermis. An intense, foreign-body granulomatous reaction

results in the formation of the acne nodule.

Interactions

between the skin’s innate immune

system and P. acnes play an important

role in acne pathogenesis. One mechanism is via Toll-like receptors (TLRs), a

class of transmembrane receptors that mediates the recognition of microbial

pathogens by immune cells (monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils) as well as

by keratinocytes. TLR2, which recognizes lipoproteins and peptidoglycans as

well as CAMP factor 1 produced by inflammatory strains of P. acnes, is found on the surface of macrophages

surrounding acne follicles. P. acnes have

also been shown to increase expression of TLR2 and TLR4 by keratinocytes.

Through activation of the TLR2 pathway, P. acnes stimulates

the release of proinflammatory mediators such as IL-1α,

IL-8, IL-12, tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α], and matrix metalloproteinases. IL-8 leads to

neutrophil recruitment, the release of lysosomal enzymes, and subsequent

disruption of the follicular epithelium, while IL-12 promotes Th1 responses.

P.

acnes has also been shown to activate the NOD-like receptor

protein 3 (NLRP3) of inflammasomes in the cytoplasm of both neutrophils and

monocytes, resulting in the release of proinflammatory IL-1β. In addition, recent studies have shown that P. acnes stimulate Th17 responses in acne lesions.

Lastly, P. acnes can induce monocytes to differentiate

into two distinct innate immune cell subsets: (1) CD209+ macrophages, which more effectively

phagocytose and kill P. acnes and

whose development is promoted by tretinoin; and (2) CD1b+ dendritic cells that activate T cells and

release proinflammatory cytokines.

Mechanisms leading to high sebum production

1.

Excessive androgen production

2.

Increased availability of free androgen which

may be associated with a relative reduction of sex hormone binding globulin

(SHBG)

3.

An amplified target response mediated through

the conversion of testosterone to more active dihydrotestosterone

4.

An increased capacity of the intracellular

receptor to bind androgens

Clinical features

Types of Acne Lesions

1.

Active lesions (increasing severity)

1.

Microcomedone (may not be clinically

apparent)

2.

Open comedone (blackhead)

3.

Closed comedone (whitehead)

4.

Papule

5.

Pustule

6.

Nodule

7.

Pseudo-cyst

2.

Sequelae

1.

Post‐inflammatory

macular erythema

2.

Dyspigmentation (usually hyper pigmentation)

3.

Scarring

Acne is a

polymorphic, inflammatory disease of the skin which occurs in sites with well-developed

sebaceous glands, most commonly on the face (in 99% of cases) and to a lesser

extent on the back (60%) and chest (15%), also on the neck and upper arms. On

the trunk, lesions tend to be concentrated near the midline. Although one type

of lesion may predominate, close inspection usually reveals the presence of

several types of lesions. Seborrhea is a frequent and distressing feature. Despite evidence that inflammation is present in even the

earliest comedones, acne lesions are divided into non-inflammatory and

inflammatory groups based upon their clinical appearance.

Non-inflamed lesions

are the earliest lesions to develop in younger patients and embrace both open

(blackheads) and closed (whiteheads) comedones. The open comedo appears as flat

or slightly raised lesion, <5

mm in diameter with a conspicuous central, dilated follicular opening

that is filled with an inspissated core of shed keratin and lipid. Melanin

deposition and lipid oxidation within the debris may be responsible for the

black coloration. They frequently appear in a mid-facial distribution and when

evident early in the onset of the disease indicate a poor prognosis. Closed

comedones or whiteheads are generally <5 mm

in diameter; dome-shaped; smooth; skin-colored,

whitish, or greyish papules and have no visible follicular opening or

associated erythema. These lesions are often inconspicuous and better

appreciated upon palpation, stretching or side-lighting of the skin. Most

patients have a mixture of lesions. Comedones are required for diagnosis of any

type of acne.

There are also

several subtle subtypes of comedones whose presence may influence response to

therapy:

• ‘Sandpaper’

comedones consist of multiple, very small whiteheads, frequently distributed on

the forehead, which produce a roughened, gritty feel to the skin.

• ‘Macrocomedones’

are large whiteheads or occasionally blackheads greater than 1 mm in diameter.

Both macro comedones and sandpaper comedones respond poorly to conventional

topical treatments.

• ‘Submarine’

comedones are large comedonal structures greater than 0.5 cm in diameter and

are resident more deeply in the skin; they are frequently the source of

recurrent inflammatory nodular lesions.

• Secondary comedones

may be produced after exposure to dioxins (chloracne), pomades (pomade acne),

topical steroids and other drugs (drug-induced acne).

Inflammatory

acne is characterized by papules, pustules, and nodules of varying severity. Inflammatory

lesions arise from microcomedo or noninflammatory lesions and can develop into

superficial or deep lesions. The superficial lesions are usually papules and

pustules (5 mm or less in diameter), and the deep lesions are nodules and pseudocysts.

Erythematous papules typically range from 1 to 5 mm in diameter. Pustules tend

to be approximately equal in size and are filled with white purulent material

and normal flora, including P. acnes. As the severity of lesions progresses,

nodules form and become markedly inflamed, indurated

and tender. Nodules are seen more frequently in males. Nodules may

become suppurative or hemorrhagic. Suppurative nodules are called cysts

because of their resemblance to inflamed epidermal cysts. But they are not true

cysts (pseudo-cyst) because they are not lined by an epithelium. These pseudocysts are deeper and filled with a combination

of pus and serosanguineous fluid. Recurring rupture and re-epithelisation

of cysts results in epithelial-lined sinus tracts.

Scarring can be a complication of both non

inflammatory and inflammatory acne. Scars may show increased collagen

(hypertrophic scars and keloids) or be associated with loss of collagen (i.e.

ice-pick scars, rolling and box scar).

Ice-pick

scars are small, narrow, deep scars that are widest at the surface of the skin

and taper to a point in the dermis, most evident on the cheeks. Ice-pick

scarring can result from comedones alone. Rolling scars are shallow, wide scars

that have an undulating appearance. Box scars are wide sharply demarcated

scars. Unlike ice pick scars, the width of the box scars is similar at the

surface and base.

Complications

Almost all acne

lesions leave a transient macular erythema after resolution. In darker skin

types, post-inflammatory hyper pigmentation persists for months after

resolution. In some individuals, acne lesions may result in permanent scarring.

Early treatment of acne is essential for the

prevention of lasting cosmetic disfigurement due to scarring.

Prognosis and clinical

course

The age of onset of

acne varies considerably. It may start as early as 8 years of age or it may not

appear until the age of 20 or later. The course is one of several years

duration followed by spontaneous remission in majority of cases. While most

patients will clear by mid-twenties (25 years), some have acne extending well

into the third or fourth decades. About 70% of women complain of a flare 2–7

days premenstrual. Possibly, flaring is related to a premenstrual change in the

hydration of the pilosebaceous epithelium. It is shown that prepubescent

females with comedonal acne and those females with high DHEAS levels are predictors

of severe nodular acne.

ACNE

VARIANTS

Gram-negative

folliculitis

Gram-negative

folliculitis can occur as a complication of long term oral or, less frequently,

topical antibiotic therapy used to treat acne due to an increased carriage rate

of gram-negative rods in the anterior nares. Patients usually give a history of

initial success with oral tetracyclines followed by a worsening of their acne.

Clinical features include a sudden eruption of multiple, small follicular

pustules or occasionally nodular lesions, most frequently localized around the

perioral or perinasal regions. Cultures of these lesions and the anterior nares

reveal Escherichia aerogenes, Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Escherichia coli, Serratia marcescens, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These

organisms replace the Gram positive flora of the facial skin and mucous

membranes.

Discontinuation of

the current antibiotic is required; treated with either ampicillin (250 mg four

times a day) or trimethoprim (600 mg/day). However, the response may be slow

and relapse is almost inevitable. Isotretinoin is now considered the treatment

of choice (1 mg/kg/day for 20 weeks); relapse following oral isotretinoin being

much less likely.

Drug-induced acne

Some drugs may cause acneform

reactions; these account for about 1% of all drug‐induced skin eruptions. Clinically,

it is characterised by an abrupt onset of monomorphic eruption of

inflammatory papules and pustules, usually pruritic and follicular, in contrast to the heterogeneous morphology of

lesions seen in acne vulgaris. Lesions are seen primarily seen on the chest and back.

Comedones are usually

absent unless androgens are the cause.

The interval between drug exposure and the acneiform eruption depends on

the offending agent. This

explains why some clinicians use the term “folliculitis”.

Major

drugs implicated in acneiform eruptions include glucorticoids, androgens/ anabolic

steroids (danazol, testosterone), hydantoins,

lithium, isoniazide, high dose of vitamin B complex, halogenides like

bromides and iodides, and oral contraceptives (more

often those that contain progestins with androgen-like effects). Less commonly,

azathioprine, quinidine, and adrenocorticotropic hormone are the culprits. With

the introduction of EGFR and MEK inhibitors, drug-induced follicular eruptions

are increasingly seen by dermatologists.

|

CAUSES OF DRUG-INDUCED

ACNE |

||||

|

Common |

Uncommon |

|||

|

Anabolic steroids (e.g.

danazol, testosterone) |

Azathioprine |

|||

|

Bromides* |

Cyclosporine |

|||

|

Corticosteroids |

Disulfiram |

|||

|

Corticotropin |

Ethosuximide |

|||

|

EGFR inhibitors |

Phenobarbital |

|||

|

Iodides† |

Propylthiouracil |

|||

|

Isoniazid |

Psoralen + ultraviolet A |

|||

|

Lithium |

Quinidine |

|||

|

MEK inhibitors (e.g.

trametinib) |

Quetiapine |

|||

|

Phenytoin |

TNF inhibitors |

|||

|

Progestins |

Vitamins B6 and B12 |

|||

* Found in

sedatives, analgesics and cold remedies.

† Found in contrast dyes, cold/asthma

remedies, kelp, and combined vitamin–mineral supplements.

With iodides, in particular, inflammation may be marked. The iodine

content of iodized salt is low and, therefore, it is extremely unlikely that

enough iodized salt could be ingested to cause this type of acne.

Steroid acne

It

is also called ‘acne vulgaris in reverse’. In predisposed individuals, sudden

onset of follicular pustules and papules may occur approximately 2 weeks after

starting corticosteroids by any route (IV,

IM, oral, inhaled, topical). The pathology of steroid acne is that of a focal

folliculitis with a neutrophilic infiltrate in and around the follicle. The

lesions of steroid acne differ from those of acne vulgaris by being of uniform

size and symmetric distribution, usually on the neck, chest, and back. Post

inflammatory hyper pigmentation may occur, but comedones, pseucysts, and

scarring are unusual. The eruption

clears when steroids are discontinued. Topical therapy with benzoyl peroxide is

effective.

Histopathology

Histopathologic

examination of acne lesions demonstrates the stages of acnegenesis that

parallel the clinical findings. In early lesions, microcomedones are seen. A

mildly distended follicle with a narrowed follicular opening is impacted by

shed keratinocytes. The granular layer at this stage is prominent. In closed

comedones, the degree of follicular distension is increased and a compact

cystic structure forms. Within the cystic space, eosinophilic keratinaceous

debris, hair, and numerous bacteria are present. Open comedones have broad,

expanded follicular ostia and greater overall follicular distension. The

sebaceous glands are typically atrophic or absent. A mild perivascular

mononuclear cell infiltrate encircles the expanding follicle.

As the follicular epithelium distends, the cystic contents inevitably begin to rupture into the dermis. The highly immunogenic cystic contents (keratin, hair and bacteria) induce a marked inflammatory response. Neutrophils first appear, creating a pustule. As the lesion matures, foreign body granulomatous inflammation engulfs the follicle and end-stage scarring can result.

Differential diagnosis

Acne is rarely

misdiagnosed. The commonest mistaken diagnosis is rosacea, which occurs in

older patients after the age of 30 years. Rosacea

favors the malar region, chin, and forehead; the presence of telangiectasias,

an absence of comedones, nodules or scarring and

a history of easy flushing can aid in diagnosis. Rosacea patients may

also have ocular involvement, but rarely have truncal lesions. Some patients

appear to have features of both diseases and clinical acne may evolve into more

typical rosacea later in life.

In females, confusion

with perioral dermatitis is possible, but in these patients the lesions itch,

the skin is dry and there are no comedones.

Whiteheads (closed

comedones) may be confused with milia. Milia represent subepidermal keratin cysts

predominantly infraorbital in distribution. They are very common and can occur

in association with, although unrelated to, acne.

Pityrosporum folliculitis

presents on the upper trunk as moderately ill-defined, superficial plaques,

among which are scattered many papules or pustules. It is likely to be a host

reaction to M. furfur, which is a normal skin commensal.

TREATMENT

General principles of acne treatment

Acne management aims

to alleviate symptoms; clear existing lesions and limit disease activity so

preventing new lesions and scars developing and avoid negative impact on

quality of life. Most cases of acne clear spontaneously as the patient matures

through adolescence into adulthood; however, even mild cases can persist for

4–6 years and in severe cases the natural history could be in excess of 12

years. Patients should be reassured that there are treatments available that

can significantly limit the disease duration, but should be informed that

response is slow and resolution is directly linked to good adherence.

A

thorough history and physical examination are key to developing an appropriate

and maximally effective treatment plan. The physician should review with the

patient all prescription and over-the-counter medications used for acne or

other conditions, and note the clinical responsiveness to them. A review of

cosmetics, sunscreens, cleansers, and moisturizers is also helpful. In female

patients, a menstrual and oral contraceptive history is important in

determining hormonal influences on acne. Some patients may report an

improvement following sun exposure while others experience an exacerbation.

|

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL

EXAMINATION OF THE ACNE PATIENT |

|

|

History |

Physical examination |

|

1. Sex 2. 3. Age 4. 5. Motivation 6. 7. Lifestyle/hobbies 8. 9. Occupation Current and previous treatments Use of cosmetics, sunscreens, cleansers, moisturizers Menstrual history Medications ·

Corticosteroids ·

Oral contraceptives ·

Anabolic steroids ·

Other (e.g. lithium, EGFR

inhibitors) Concomitant illnesses Family history (including severity of acne, polycystic ovary

syndrome, inflammatory disease) |

1. Skin type (e.g. oily versus dry) 2. Skin colour/photo type 3. Distribution of acne · Face (e.g. “T-zone”, cheeks, jaw line) · Neck, chest, back, upper arms 4. Overall degree of involvement (mild, moderate or severe) 5. 6. Lesion morphology · Comedones · Papules, pustules · Nodules, pseudocysts · Sinus tracts 7. 8. Scarring · Pitted · Hypertrophic · Atrophic 9. Post inflammatory pigmentary changes |

On

physical examination, lesional morphology should be assessed, including the

presence of comedones, inflammatory lesions, nodules, and pseudocysts.

Secondary changes such as scarring and post inflammatory pigmentary changes are

also important clinical findings. The patient’s skin colour and type can

influence the chosen formulation of a topical medication. For example, patients

with oily skin tend to prefer the more drying gels and lotions, whereas those

with drier skin types may prefer creams.

Treatment

of acne vulgaris

Treatment

goals include scar prevention, reduction of psychological morbidity, and

resolution of lesions. Grading acne based on lesion type and severity can help

guide treatment. Topical retinoids are effective in treating inflammatory and

non-inflammatory lesions by preventing comedones, reducing existing comedones,

and targeting inflammation. Benzoyl peroxide is an over-the-counter

bactericidal agent that does not lead to bacterial resistance. Topical and oral

antibiotics are effective as monotherapy, but are more effective when combined

with topical retinoids. The addition of benzoyl peroxide to antibiotic therapy

reduces the risk of bacterial resistance. Oral isotretinoin is approved for the

treatment of severe recalcitrant acne and can be safely administered using the

iPLEDGE program. After treatment goals are reached, maintenance therapy should

be initiated. There is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of laser and

light therapies.

GUIDELINES

OF CARE FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF ACNE VULGARIS (J AM ACAD DERMATOL 2016; 74:945-73)

Treatment algorithm for adolescents and young adults

* May be prescribed as

a fixed combination product or as separate component.

Recommendations for

topical therapies

Benzoyl peroxide or combinations with

clindamycin are effective acne treatments and are recommended as monotherapy

for mild acne, or in conjunction with a topical retinoid, or systemic

antibiotic therapy for moderate to severe acne

Benzoyl peroxide is effective in the

prevention of bacterial resistance and is recommended for patients on topical

or systemic antibiotic therapy. Topical antibiotic (eg, clindamycin) is

effective acne treatments, but is not recommended as monotherapy because of the

risk of bacterial resistance. Topical retinoids are important in addressing the

development and maintenance of acne and are recommended as monotherapy in

primarily comedonal acne, or in combination with topical or oral antimicrobials

in patients with mixed or primarily inflammatory acne lesions. Using multiple

topical agents that affect different aspects of acne pathogenesis can be

useful. Combination therapy should be used in the majority of patients with

acne. Topical adapalene and benzoyl peroxide can be safely used in the

management of preadolescent acne in children Azelaic acid is a useful

adjunctive acne treatment and is recommended in the treatment of post

inflammatory hyper pigmentation Topical dapsone 5% gel is recommended for

inflammatory acne, particularly in adult females with acne.

Recommendations for

systemic antibiotics

Systemic antibiotics are recommended in the

management of moderate and severe acne and forms of inflammatory acne that are

resistant to topical treatments

Doxycycline and minocycline are more

effective than tetracycline, but neither is superior to each other. Doxycycline

and lymecycline should be selected in preference to minocycline.

Although oral erythromycin and azithromycin

can be effective in treating acne, its use should be limited to those who

cannot use the tetracyclines (ie, pregnant women or children <8 years of

age). Erythromycin use should be restricted because of its increased risk of

bacterial resistance.

Use of systemic antibiotics, other than the

tetracyclines and macrolides, is discouraged because there are limited data for

their use in acne.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and

trimethoprim use should be restricted to patients who are unable to tolerate

tetracyclines or in treatment-resistant patients

Systemic antibiotic use should be limited to

the shortest possible duration. Re-evaluate at 3-4 months to minimize the

development of bacterial resistance.

Monotherapy with systemic antibiotics is not

recommended Concomitant topical therapy with benzoyl peroxide or a retinoid

should be used with systemic antibiotics and for maintenance after completion

of systemic antibiotic therapy

Recommendations for

hormonal agents

Estrogen-containing combined oral

contraceptives are effective and recommended in the treatment of inflammatory

acne in females. Spironolactone is useful in the treatment of acne in select

females.

ACNE MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES

BY THE DERMATOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF SINGAPORE

Mild acne

Comedonal acne

Limited

data suggest that increasing concentrations of tretinoin cream (i.e., 0.01%,

0.025%, 0.05%, and 0.1%) are associated with increased efficacy but with an

increased rate of side effects. In comparison, adapalene 0.1% gel or cream

causes less irritation versus tretinoin and is as efficacious as tretinoin

cream.

Azelaic acid 20% is a mild comedolytic with

anti-inflammatory activity. It is safe and effective as a treatment and

maintenance option for women with adult acne. It can be used during

pregnancy and can be useful in patients with acne and PIH, as it induces

hypopigmentation in darker skin. BPO (2.5%, 5%,

and 10%) has anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and mild comedolytic activities

and does not induce bacterial resistance. Lower concentrations of BPO

(2.5% or 5%) are preferred, as there is increased irritation with increasing

concentrations of BPO and without a significant increase in efficacy between

the 2.5% and 10% concentrations.

Mild Papulopustular acne

Recommended

treatment for mild papulopustular acne includes fixed-combination products

containing BPO (with clindamycin or adapalene) with or without topical

retinoid/azelaic acid. The topical fixed-combination products are

effective in the treatment of mild-to-moderate papulopustular acne and can be

used as monotherapy applied once-daily.

Moderate

papulopustular acne

Treatment

recommendations for moderate papulopustular acne include fixed combinations of

antibiotics and/or adapalene/BPO and/or topical azelaic acid. Treatment

duration with systemic antibiotics should not exceed 3 to 4 months. At Week 6

of therapy, the patient’s response to treatment should be assessed. The use of

oral antiandrogens as an alternative second-line treatment might be suitable

for some women with moderate papulopustular acne.

Severe Papulopustular acne

Treatment recommendations include the use of oral antibiotics, topical retinoid/azelaic acid, BPO, and oral antiandrogen combinations. Topical treatment alone is not recommended. Patients should be followed closely to monitor treatment response, and second-line therapy should be considered when treatment response is inadequate after a suitable amount of time. Some doctors combine oral contraceptives with systemic antibiotics; however, there is insufficient data on the potentially superior efficacy of this approach.

Nodulocystic and conglobate acne

For these types of acne, oral

isotretinoin is the recommended treatment. For

severe nodular/conglobate acne a high dosage of oral isotretinoin of ≥0.5 mg/kg

can be recommended (120 to 150mg/kg cumulative dose). For

severe papulopustular or moderate nodular acne, 0.3 to 0.5mg/kg for six months can

be recommended. A daily dose of 0.25 to 0.5mg/kg

can be started and adjusted as tolerated. Pulse therapy (every 1 to 3 weeks) is

not recommended due to higher relapse rates. Low-dose maintenance for

persistent acne in adults can be considered, but with caution due to the

potential for adverse events (e.g., teratogenicity, hepatotoxicity,

hyperlipidemia). Lastly, combination with oral tetracyclines should be avoided

due to the risk of pseudotumour cerebri.

·

COCs are

effective for noninflammatory and inflammatory acne. They may be considered

alternatives to systemic antibiotics or systemic retinoids for

moderate-to-severe papulopustular acne in women, in combination with topical

retinoids with or without BPO.

|

TIPS FOR TOPICAL ACNE

THERAPY |

|

|

Improve adherence – often compromised due to patients having busy schedules

or quitting when the response is not rapid |

· Simplify the regimen: once daily when possible; consider

combination products (e.g. benzoyl peroxide + adapalene or clindamycin; adapalene

+ clindamycin), especially in less motivated adolescents · Inform patients that it will take 6–8 weeks of treatment for

substantial improvement · Ask specifically about adherence: “Out of 7 nights, how many

times do you apply the medication?” |

|

Educate on proper use |

· In general, topical medications (especially retinoids) should be

used to the entire acne-prone region rather than as “spot treatment” of

individual lesions · Provide instructions on where to apply the medication and how

much to use |

|

Minimize irritation – most common in adolescents with atopic dermatitis and

adults |

· Note that using too much medication or applying it too

frequently can increase irritation · Devise a gradual initial approach to improve tolerance in

patients with sensitive skin; for example, a single agent may be used for the

first 2–3 weeks (starting every other day for retinoids), followed by slow introduction

of a second medication (e.g. transitioning from alternate days to daily) · Advise to avoid harsh scrubs and other irritating agents (e.g.

toners, acne products that are not part of the regimen) · Suggest use of a non-comedogenic sensitive skin moisturizer if

dryness occurs |

|

Avoid exacerbation |

· Review all skin care products and cosmetics; having patients

bring everything that they apply to their face to a visit may help to

determine the source of problems · Advise non-comedogenic products (e.g. moisturizers, sunscreens,

make-up) and to avoid having oily hair or using pomades that may contribute

to acne. · Instruct patients not to pick or manipulate lesions |

|

|

|

Choice of therapy

This is largely

determined by the severity and extent of the disease.

Patients with mild

acne usually receive topical therapy alone; patients with moderate acne receive

oral and topical therapies; patients with more severe acne should be started on

oral antibiotic therapy but the need to commence oral isotretinoin should be

considered early in the course of their disease and may well be used first line

in those patients demonstrating poor prognostic factors which are associated

with more severe disease, as outlined in Table.

Table Poor prognostic factors in acne

Family history

Early onset:

Mild facial comedones

Early and more severe sebum production

Early onset relative to menarche

Hyperseborrhoea

Site of acne:

Truncal

Scarring

Persistent

Mode of action of therapeutic agents

Acne severity grading

Comedonal

acne

Non-inflammatory

acne lesions consisting of open and closed comedones

Mild

inflammatory acne

Few comedones,

papules and pustules (<10), no nodules, no scarring

Moderate

inflammatory acne

Several

comedones, papules and pustules (10-40) and few nodules up to 5, mild scarring

Severe

inflammatory acne

Numerous

comedones, papules and pustules (>40), multiple nodules >5, scarring

Severity-based approach to treating acne

Comedonal acne

Clinical

presentation

The

earliest type of acne is usually noninflammatory comedones (“blackheads” and

“whiteheads”). It develops in the pre-teenage or early teenage years and is

caused by increased sebum production and abnormal desquamation of epithelial

cells. There are no inflammatory lesions because colonization with P. acnes

has not yet occurred.

Treatment

Closed

comedone acne (whiteheads) responds slowly. A large mass of sebaceous material

is impacted behind a very small follicular orifice. The orifice may enlarge

during treatment, making extraction by acne surgery possible. Comedones may

remain unchanged for months or evolve into a pustule or nodule.

Retinoids

are applied at bedtime (tazarotene, tretinoin, adapalene). The base and

strength are selected according to skin sensitivity. Tazarotene may be the most

effective and most irritating. Start with a low concentration of the cream or

gel (available in 0.05% and 0.1%) and increase the concentration if irritation

does not occur. Tretinoin and adapalene are equally effective. Start with Tretinoin

such as Retin-A Micro (0.04% or 0.1%) or adapalene gel. Medications are used

more frequently if tolerated. Add benzoyl peroxide or topical antibiotics or combination

medicines later to discourage P. acne and the formation of inflammatory

lesions. The response to treatment is slow and discouraging. Several months of

treatment are required. Large open comedones (blackheads) are expressed; many

are difficult to remove. Several weeks of treatment facilitate easier

extraction. Topical therapy may need to be continued for extended periods.

Mild inflammatory acne

Clinical

presentation

Mild pustular and

papular inflammatory acne is defined as fewer than 20 pustules.

Treatment

Benzoyl

peroxide, a topical antibiotic, or combination medicine and a retinoid are

initially applied on alternate evenings. The lowest concentrations are

initially used. After the initial adjustment period, the retinoid is used each

night and benzoyl peroxide or antibiotic is used each morning. The strength of

the medications is increased if tolerated. Oral antibiotics are introduced if

the number of pustules does not decrease. Topical therapy may require

continuation for extended periods.

Moderate-to-severe inflammatory acne

Clinical

presentation

Patients who have moderate-to-severe

acne (more than 20 pustules) are temporarily disfigured.

The

explosive onset of pustules can sometimes be precipitated by stress. There may

be few to negligible visible comedones. Affected areas should not be irritated

during the initial stages of therapy.

Treatment

Many

dermatologists will begin with a topical retinoid and combine it with a topical

antibiotic. Others will treat with twice-daily application of a topical

antibiotic, benzoyl peroxide, or combination medicine. Response to treatment

may occur in 2 to 4 weeks. Oral antibiotics (doxycycline or minocycline) are

used for patients with more than 10 pustules. Treatment should be continued

until no new lesions develop (2 to 4 months) and then should be slowly tapered.

If there are any signs of irritation, the frequency and strength of topical

medicines should be decreased. Irritation, particularly around the mandibular

areas and neck, worsens pustular acne.

A

retinoid can be introduced if the number of pustules and the degree of inflammation

has decreased. Start minocycline at full dosage if there is no response to

doxycycline after 3 months. Pustules are gently incised and expressed.

Injecting each pustule with a very small amount of triamcinolone acetonide

(Kenalog 2.5 to 5.0 mg/ml) can give immediate and very gratifying results.

Those

who have responded well may begin to taper and eventually discontinue oral

antibiotics.

Patients

who do not respond to conventional therapy may have lesions that are colonized

by gram-negative organisms. Cultures of pustules and nodules are obtained and

an appropriate antibiotic such as ampicillin is started. The response may be

dramatic.

Severe: Nodular acne

Nodular acne

is a serious and sometimes devastating disease that requires aggressive

treatment. The face, chest, back, and upper arms may be permanently mutilated

by numerous atrophic or hypertrophic scars. Patients sometimes delay seeking

help, hoping that improvement will occur spontaneously; consequently, the

disease may be quite advanced when first viewed by the physician.

Patients

with a few inflamed nodules can be treated by implementing a program similar to

that outlined for moderate-to-severe inflammatory acne. Oral antibiotics,

conventional topical therapy, and periodic intralesional Kenalog injections may

keep this problem under adequate control.

Extensive nodular

acne requires a different approach. There are three less common variants of

nodular acne—pyoderma faciale, acne fulminans, and acne conglobata.

Pyoderma

faciale

The illness typically

appears in the mid face of post adolescent women of 20–40 years of age. It is

reported to occur in the context of traumatic emotional experience with sudden

explosives eruption of pustules and nodules, which may be interconnected by

sinuses. Marked erythema and oedema are usually present. Comedones are usually

absent. There is often no preceding history of acne. Facial flushing frequently

precedes the exacerbation. As the name

implies, the eruption is usually confined to the face, involving the cheeks,

chin, nose and forehead. In contrast to acne fulminans, there are usually no

systemic symptoms.

The daily ingestion

of high-dose vitamin B supplements has also been reported to be associated with

the sudden onset of pyoderma faciale.

Cultures help to differentiate

this condition from gram-negative acne. Highly inflamed lesions can be managed

by starting isotretinoin and oral corticosteroids. A study reported effective

management with the following: Treatment was begun with prednisolone (1.0 mg/kg

daily for 1 to 2 weeks). Isotretinoin was then added (0.2 to 0.5 mg/kg/day

[rarely, 1.0 mg/kg in resistant cases]), with a slow tapering of the

corticosteroid over the following 2 to 3 weeks. Isotretinoin was continued

until all inflammatory lesions resolved. This required 3 to 4 months. None of the

patients had a recurrence. This group of patients were “flusher and blushers,”

and it was suggested that pyoderma faciale is a type of rosacea. The

investigators proposed the term rosacea fulminans.

Acne

fulminans

Acne

fulminans is the most severe form of acne and is characterized by the abrupt

development of nodular and suppurative acne lesions in association with

systemic manifestations. This uncommon

variant primarily affects boys 13–16 years of age. Patients typically have mild

to moderate acne prior to the onset of acne fulminans, when numerous

microcomedones suddenly erupt and become markedly inflamed. There is rapid

coalescence into painful, oozing, friable plaques with hemorrhagic crusts.

There may be confluent abscesses leading to ulcer formation. The lesions

predominate on the chest and back and heal with significant scarring.

Aseptic osteolytic bone lesions causing bone pain may accompany

the cutaneous findings in approximately 40% of patients; the clavicle and

sternum are most commonly affected, followed by the ankles, humerus and

iliosacral joints. Systemic manifestations include fever, arthralgias,

myalgias, hepatosplenomegaly and severe malaise. Erythema

nodosum may also arise in association with acne fulminans. Laboratory

abnormalities vary and include an elevated ESR, proteinuria, leukocytosis, and

anemia. Laboratory studies are not required to establish the diagnosis,

but their evolution may parallel the clinical course and response to therapy. The related synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO)

syndrome, which can accompany acne fulminans. Acne fulminans has also been

associated with late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia and anabolic steroid

use, including therapeutic testosterone.

Antibiotic therapy is not effective. Recommended treatment of acne fulminans includes prednisone

0.5–1 mg/kg/day as monotherapy for at least 2–4 weeks, followed by initiation

of low-dose isotretinoin (e.g. 0.1 mg/kg/day) after the acute inflammation

subsides; after at least 4 weeks of this combination, the isotretinoin dose can

be slowly increased and the prednisone tapered over a period of 1–2 months.

Paradoxically, an acne fulminans-like flare

occasionally develops during the first few weeks of isotretinoin therapy for

acne; this may be avoided by starting with a low dose of isotretinoin and

concomitant administration of oral corticosteroids at the first sign of a flare

or possibly pre-emptively in high-risk patients. Additional treatment options

for acne fulminans include topical or intralesional corticosteroids, TNF-α inhibitors, interleukin-1 antagonists, and

immunosuppressive agents (e.g. azathioprine, cyclosporine). Dapsone may be

particularly beneficial in the treatment of acne fulminans associated with

erythema nodosum

The main features of acne fulminans

|

Gender |

Male gender dominant |

|

Age |

13–22

years |

|

Pathogenesis |

Unclear |

|

Onset |

Acute

and sudden |

|

Localization |

Upper

chest and back, shoulders, face |

|

Clinical

picture |

Ulcerative

lesions covered with hemorrhagic crusts healing with scarring |

|

Laboratory

findings |

Leucocytosis,

increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, anemia, proteinuria, microscopic

hematuria |

|

Response

to conventional antibiotic therapy |

Poor |

|

Treatments

of choice |

Systemic

corticosteroids combined with isotretinoin |

Acne

conglobata

This is a severe form

of nodular acne and affects men more often than women with no or little

systemic upset. This acne variant is part of the follicular occlusion tetrad

along with dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, hidradenitis suppurativa and

pilonidal cysts. Lesions usually occur on the trunk (chest and back) and upper

limbs and frequently extend to the buttocks. In contrast to ordinary acne,

facial lesions are not common. The condition often presents in the second to

third decade and may persist into the 40s and 50s. The involved areas contain a

mixture of multiple grouped comedones, papules, pustules, nodules, abscesses,

draining sinuses and scars, often both keloidal and atrophic.

The

association of sterile pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum,

and acne conglobata can occur in the context of an

autosomal dominant autoinflammatory disorder referred to as PAPA syndrome.

The main features of acne conglobata

|

Sex |

Males

affected more frequently than females |

|

Age |

18–30

years |

|

Pathogenesis |

Unclear |

|

Onset |

May

be an insidious onset with a chronic course on the background of previous

acne or an acute deterioration of existing inflammatory acne |

|

Localisation |

Face,

trunk and limbs extending to the buttocks |

|

Clinical

picture |

Deep‐seated

inflammatory lesions, abscesses and cysts, causing interconnecting sinus

tracts. Polyporous grouped comedones and, significant scarring |

|

Laboratory

findings |

Gram‐positive

bacteria producing secondary infection |

|

Response

to conventional antibiotic therapy |

Poor |

|

Treatments

of choice |

Oral isotretinoin alongside

systemic corticosteroids to reduce inflammation Systemic

antibiotics to treat secondary infection and reduce inflammation |

Differential diagnosis of acne fulminans and

acne conglobate

|

|

Acne fulminans |

Acne conglobata |

|

Gender |

Men |

Men |

|

Age |

Adolescence

(13–16 years) |

20–25

years |

|

Onset |

Sudden |

Slow |

|

Location |

Face,

neck, chest and back |

Trunk

and upper limbs, facial lesions are rare |

|

Clinical

features |

Hemorrhagic

ulcerations |

Nodules,

inflammatory cysts, grouped comedones |

|

Systemic

symptoms |

Very

common |

None |

Therapeutic

agents for treatment of acne

Topical acne therapies

Topical

agents should be applied to the entire affected area to treat existing lesions

and to prevent the development of new ones. The most widely used topical drugs

are benzoyl peroxide (BPO), retinoids, antibiotics and azelaic acid, either as

monotherapy or in combinations. Earlier it was suggested that topical retinoids

should be limited to the treatment of comedonal lesions because of potential to

aggravate inflammatory acne. It has now been shown that topical retinoids have

some anti-inflammatory activity and also impact on the microcomedo, which

represents the precursor of non-inflammatory and inflammatory lesions. As a

result of these findings, topical retinoids are now ideally combined with

antimicrobials and should be considered in treating acne from the onset of acne

management. Topical BPO, antibiotics or azelaic acid have predominantly anti-inflammatory

activity in acne and can be used safely in combination with topical retinoids,

with the exception of tretinoin which is inactivated if used simultaneously

with BPO.

Topical retinoids

Topical retinoids are versatile agents in the treatment of

acne. The

anti-acne activity of topical retinoids involves normalization of follicular

keratinization and corneocyte cohesion, which aids in the expulsion of existing

comedones and prevents the formation of new ones, making them useful against noninflammatory lesions. Topical

retinoids also have significant anti-inflammatory properties, making them somewhat useful in the treatment of inflammatory

lesions. Topical retinoids are indicated as monotherapy for noninflammatory

acne and as combination therapy with antibiotics to treat inflammatory acne. Additionally, they are useful for maintenance after

treatment goals have been reached and systemic drugs are discontinued. In

addition, concurrent use of a topical retinoid can enhance the efficacy of

benzoyl peroxide and topical antibiotics by increasing the penetration of the

latter medications into the sebaceous follicle. The enhanced penetration

results in a synergistic effect with greater overall drug efficacy and a faster

response to treatment. Topical retinoids used for acne include tretinoin,

adapalene and tazarotene. Overall,

adapalene is the best tolerated topical retinoid. Limited evidence suggests

that tazarotene is more effective than adapalene and tretinoin. There is no

evidence that any formulation is superior to another. Topical products that

combine tretinoin with clindamycin or adapalene with benzoyl peroxide are also

available. The fixed-dose adapalene

0.1%–benzoyl peroxide 2.5% combination gel is an efficacious and safe acne

treatment.

The most common side effect of topical retinoids is local

irritation resulting in erythema, dryness, peeling, and scaling. This tends to

peak after 2–4 weeks of treatment and improve with continued usage. Continual

topical application leads to thinning of the stratum corneum, making the skin

more susceptible to sunburn, sun damage, and irritation from wind, cold, or

dryness. Irritants such as astringents, alcohol, and acne soaps will not be

tolerated as they were previously; transient

application of a low-potency topical corticosteroid may be of benefit for

patients with significant irritation. Delivery systems have been developed to

permit a greater concentration of retinoid while decreasing irritancy,

primarily through controlled slow release, e.g. tretinoin impregnated into inert

microspheres or incorporated within a polyolprepolymer. An acne flare may occur

during the initial month of treatment with a topical retinoid, but resolves

spontaneously with continued usage. Although not true photosensitizers, if a

retinoid causes skin peeling or irritation, this may increase the user’s

susceptibility to sunburn. Appropriate use of sunscreens should therefore be

advised.

Tretinoin (all-trans-retinoic acid), a naturally occurring metabolite

of retinol, was the first topical comedolytic agent used for the treatment of

acne. To decrease the potential for irritation, treatment is often started with

a lower-concentration cream formulation of tretinoin and the strength later

increased. Alternate-night to every-third-night application may be necessary

initially, with increased frequency as tolerated. Because the standard generic

tretinoin formulation is photolabile, night-time application is recommended to

prevent early degradation; it is also inactivated by concomitant application of

benzoyl peroxide, so the two medications should not be used at the same time.

However, specialized microsphere formulations of tretinoin are not photolabile

and can be applied together with benzoyl peroxide without degradation.

Although

epidemiologic studies have not shown an increased risk of birth defects in

infants of mothers using topical tretinoin during the first trimester, sporadic

case reports of birth defects have been published. Because of this and the fact

that systemic retinoids are known teratogens, the use of topical tretinoin in

pregnancy is discouraged. That said, dietary intake of vitamin A has been shown

to have a greater influence on serum retinoid levels than facial application of

tretinoin.

The

synthetic retinoid adapalene is an

aromatic naphthoic acid derivative. In the skin, it primarily binds the

retinoic acid receptor γ (RARγ), whereas tretinoin binds to both RARα and RARγ. Although

animal studies have shown adapalene to have milder comedolytic properties than

tretinoin, it is also less irritating. Unlike tretinoin, adapalene is

light-stable and resistant to oxidation by benzoyl peroxide.

Tazarotene is

a synthetic acetylenic retinoid that, once applied, is converted into its

active metabolite, tazarotenic acid. Like adapalene, this metabolite

selectively binds RARγ but not RARα or RXR. Both daily overnight applications of

tazarotene and short contact therapy regimens have been shown to be effective

in the treatment of comedonal and inflammatory acne. Topical tazarotene has

been designated pregnancy category X, so contraceptive counseling should be

provided to all women of childbearing age who are prescribed this medication.

Like adapalene, it is light-stable and can be applied together with benzoyl

peroxide.

Application techniques

The

skin should be washed gently with a mild soap no more than two to three times

each day, using the hands rather than a washcloth. Special acne or abrasive

soaps should be avoided. To minimize possible irritation, the skin should be

allowed to dry completely by waiting 20 to 30 minutes before application of

retinoids. The retinoid is applied in a thin layer once daily. Medication is

applied to the entire area, not just to individual lesions. A pea-sized amount

is enough for a full facial application. Patients with sensitive skin or those

living in cold, dry climates may start with an application every other or every

third day. The frequency of application can be gradually increased to as often

as twice each day if tolerated. The corners of the nose, the mouth, and the

eyes should be avoided; these areas are the most sensitive and the most easily

irritated. Retinoids are applied to the chin less frequently during the initial

stages of therapy; the chin is sensitive and is usually the first area to

become red and scaly. Sunscreens should be worn during the summer months if

exposure is anticipated.

Response to treatment

1

to 4 weeks: During the first few weeks, patients may experience

redness, burning, or peeling. Those with excessive irritation should use less

frequent applications (i.e., every other or every third day). Most patients

adapt to treatment within 4 weeks and return to daily applications. Those

tolerating daily applications may be advanced to a higher dosage or to the more

potent solution.

Three

to 6 weeks: New papules and pustules may appear because comedones

become irritated during the process of being dislodged. Patients unaware of

this phenomenon may discontinue treatment. Some patients do not worsen and

sometimes begin to improve dramatically by the fifth or sixth week.

After

6 weeks:

Most patients improve by the ninth to twelfth week and exhibit continuous

improvement thereafter. Some patients never adapt to retinoids and experience

continuous irritation or continue to worsen. An alternate treatment should be

selected if adaptation has not occurred by 6 to 8 weeks. Some patients adapt

but never improve. Retinoids may be continued for months to prevent appearance

of new lesions.

Benzoyl

peroxide (BPO)

Benzoyl peroxide is

an over-the-counter bactericidal agent that comes in a wide array of

concentrations and formulations. No particular form has been proven better than

another. Benzoyl peroxide is unique as an antimicrobial because it is not

known to increase bacterial resistance. It is most effective for the

treatment of mild to moderate mixed acne when used in combination with topical

retinoids. Benzoyl peroxide may also be added to regimens that include

topical and oral antibiotics to decrease the risk of bacterial

resistance.

BPO is a potent bactericidal agent that rapidly destroys

both surface and ductal P. acnes and yeasts. The lipophilic nature of

BPO allows it to penetrate the pilosebaceous duct. Once applied to the skin it

decomposes to release free oxygen radicals with potent bactericidal activity in

the sebaceous follicles and anti-inflammatory action. Benzoyl peroxide causes a

significant reduction in the concentration of free fatty acids via its

antibacterial effect on P. acnes. BPO has only mild comedolytic activity

and reduces the number of non-inflamed lesions

by decreasing follicular hyperkeratosis, but it is less effective than

retinoids at disrupting the microcomedo.

It does not impact on sebum production. In contrast to topical

antibiotics, microbial resistance to benzoyl peroxide has not been reported.

Many preparations for all skin types are available and includes bar soaps,

washes and gels, in concentrations ranging from 2.5% to 10% as well as products

that combine benzoyl peroxide with clindamycin or adapalene.

As benzoyl peroxide is a bleaching agent, whitening of clothing

and bedding can occur. Development of irritant contact dermatitis to benzoyl

peroxide may occur, and this should be suspected in patients who develop marked

erythema with its use. Although rare, approximately 2% of patients develop

allergic contact dermatitis from benzoyl peroxide and must discontinue its use.

The sudden appearance of diffuse erythema and vesiculation suggests contact

allergy to benzoyl peroxide.

BPO is particularly effective when used in combination with other

therapies. The

combination of clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide (Benza-Clin) is superior for

inflammatory and non-inflammatory acne versus either ingredient used alone.

Principles of

treatment

Benzoyl

peroxide should be applied in a thin layer to the entire affected area. Most

patients experience mild erythema and scaling during the first few days of

treatment, even with the lowest concentrations, but adapt in a week or two. An

adequate therapeutic result can be obtained by starting with daily applications

of the 2.5% or 5% gel and gradually increasing or decreasing the frequency of

applications and strength until mild dryness and peeling occur.

Topical

antibiotics

Topical antibiotics

are used predominantly for the treatment of mild to moderate inflammatory or

mixed acne. In comedones they reduce the perifollicular lymphocytes which are

involved in comedogenesis. They also significantly reduce numbers and function

of P. acnes. Some topical antibiotics also have a direct anti-inflammatory

action via an antioxidant effect on leukocytes. They are sometimes used as

monotherapy, but are more effective in combination with topical retinoids. Clinical trials have demonstrated that

application twice a day is as effective as oral minocycline 50 mg taken twice

daily. Most solutions are alcohol-based and may produce some degree of

irritation. Clindamycin lotion or gel is a commonly used topical antibiotic;

however, resistance of >50% of P. acnes strains

to this molecule has been reported in some countries.

Because of the

possibility that topical antibiotics may induce resistance, it is recommended

that benzoyl peroxide be added to these regimens.

Azelaic acid

Azelaic acid is a naturally occurring dicarboxylic

acid found in cereal grains that has antikeratinizing, antibacterial, and antiinflammatory

properties, but is not sebosuppressive. The

cream formulation is approved by the U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for

the treatment of acne vulgaris, but the gel has significantly better

bioavailability. It is available as a topical 20% cream, which has been

shown to be effective in inflammatory and comedonal acne, as well as a 15% gel

marketed for rosacea. By inhibiting the growth of P. acnes, azelaic acid

reduces inflammatory acne. Azelaic acid reduces comedones by normalizing the

disturbed terminal differentiation of keratinocytes in the follicle

infundibulum. The activity of azelaic acid against inflammatory lesions may be

greater than its activity against comedones. Its efficacy can be enhanced when it is used in

combination with other topical medications such as benzoyl peroxide 4% gel,

clindamycin 1% gel. Azelaic acid cream may be combined with oral antibiotics

for the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne and may be used for maintenance

therapy when antibiotics are stopped. It does not cause sun sensitivity. It

does not induce resistance in P. acnes. Azelaic acid is

applied twice daily and its use is reported to have fewer local side effects

than topical retinoids. In addition, it may help to lighten post inflammatory

hyperpigmentation.

Topical

nicotinamide

Topical nicotinamide

4% has anti-inflammatory actions and doesnot induce P. acnes resistance.

A comparison of 4% nicotinamide gel demonstrated it to be similar in efficiency

to 1% clindamycin gel.

Salicyclic

acid

Salicylic acid is a

widely used comedolytic and mild anti-inflammatory agent thus reducing both non-inflammatory and inflammatory acne

lesions. It is also a mild chemical irritant that works in part by

drying up active lesions. Salicylic acid is available in concentrations of up

to 2% in numerous delivery formulations, including gels, and washes. Side

effects of topical salicylic acid include erythema and scaling.

Topical

dapsone

Topical dapsone

5% gel is approved for the treatment of acne vulgaris as it has antibacterial

and anti-inflammatory properties. Although it is an antibiotic, it likely

improves acne by inhibiting inflammation. Of note, a temporary yellow–orange

staining of the skin and hair occasionally occurs with concomitant use of

topical dapsone and benzoyl peroxide. Unlike oral dapsone, there is no evidence

that the topical formulation causes hemolyticanemia or severe skin reactions.

It is mostly used for inflammatory acne in females.

Topical

steroids

Potent steroids such as

clobetasol propionate applied twice a day for 5 days can dramatically reduce

the inflammation in an active inflammatory nodule.

Selecting topical therapy

Patients with mixed

lesions should be prescribed therapy active against comedones, inflammatory

lesions and microcomedones from the outset. Given the fact that the microcomedo

is the precursor to inflammatory and non-inflammatory lesions, even patients

with predominantly inflammatory acne should be prescribed a topical retinoid as

part of their regimen. Topical therapy should be prescribed alone for mild

acne, in conjunction with appropriate oral acne therapy for moderate acne, and

as maintenance therapy after oral therapy has stopped.

Topical therapy may

be necessary for many years. It is also important to stress to the patient that

topical therapy should be applied to all areas of skin within the active site

and not just visible lesions as clinically normal looking skin in an acne-prone

site is likely to have many evolving microcomedones. The concept of acne

prevention must be stressed to the patient. In conclusion, combined topical

therapies should be used for patients with mild inflammatory acne. Topical

retinoids have anti-inflammatory and comedolytic activity which makes them

suitable for treatment of comedonal and mild to moderate inflammatory disease

and they should therefore be used at the onset of treatment combined with

topical or oral antimicrobials. Topical retinoids are also advocated in

conjunction with oral antibiotics in patients with moderate and severe acne and

as maintenance treatment after cessation of systemic treatment. Selecting

therapies that work synergistically and impact on as many etiological factors

as possible will enhance treatment success. Products that combine preparations should

in theory be more convenient for patients to use and so aid adherence.

An Open-label Extension Study was conducted

Evaluating Long-term Safety and Efficacy of FMX101 4% Minocycline Foam for

Moderate-to-Severe Acne Vulgaris. The study concluded that FMX101 4%

minocycline foam, a new topical treatment option for patients with moderate

to-severe acne and appears to be safe, effective, and well tolerated for up to

52 weeks of treatment.

Oral

Treatments

Antibiotics

Mechanism

of action

The

primary mechanism of action of antibiotics is suppression of the growth of

follicular populations of P. acnes, thereby reducing bacterial

production of inflammatory factors. Neutrophil chemotactic factors are secreted

during bacterial growth, and these may play an important role in initiating the

inflammatory process. Because several antibiotics used to treat acne can

inhibit neutrophil chemotaxis in vitro, they are thought to act as an anti-inflammatory

agent.

Long-term

treatment

Patients