Atopic dermatitis

Salient features

·

AD is a common chronic

inflammatory skin condition that typically begins during

infancy or early childhood and is often associated with other atopic disorders

such as asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and food allergies.

·

It represents a complex genetic

disease with environmental influences and an underlying defect in the epidermal

barrier as well as associated immune dysregulation.

·

Characterized by intense pruritus and a chronically relapsing

course.

·

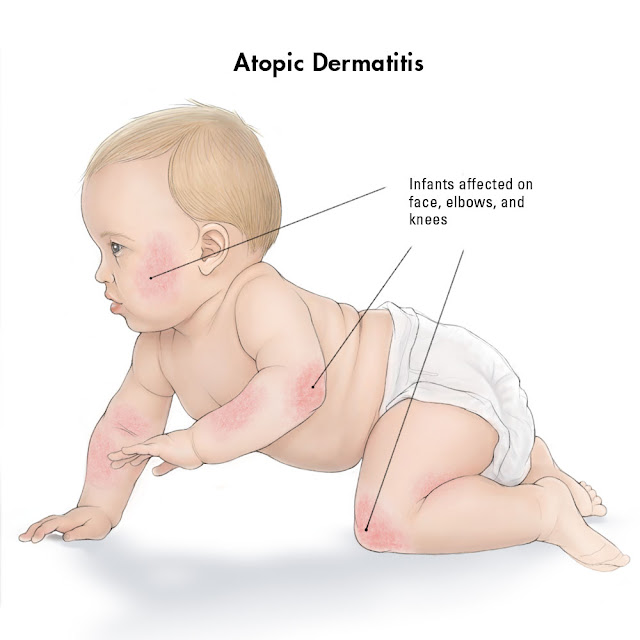

Acute inflammation and involvement of the cheeks, scalp and

extensor aspects of the extremities predominates in infants, shifting to

chronic inflammation with lichenification and a predilection for flexural sites

in children and adults

·

Associated with a predisposition to skin infections, especially

with Staphylococcus aureus and herpes simplex virus.

·

A proactive approach to management is recommended, including

avoidance of trigger factors, regular use of emollients, and anti-inflammatory

therapy to control subclinical inflammation as well as overt flares; targeted

immunomodulatory therapy is available for more severe disease.

Introduction

AE

is an itchy, chronic or chronically relapsing inflammatory skin condition that

often starts in infancy or early

childhood (usually before 2 years of age). Acute inflammation and involvement of the cheeks, scalp and

extensor aspects of the extremities predominates in infants and young children shifting

to chronic inflammation with lichenification and a predilection for flexural

sites in older children and adolescent/adults.

The term atopy denotes a familial tendency to develop

certain diseases (rhinoconjunctivitis, asthma, atopic eczema) on the basis of

hypersensitivity of skin and mucous membranes to environmental substances

associated with increased IgE formation and/or epithelial barrier dysfunction.

Atopic dermatitis usually occurs in people who have an 'atopic

tendency'. This means they may develop any or all of three closely linked

conditions; atopic dermatitis, asthma and hay

fever (allergic rhinitis). Often these conditions run within families with a

parent, child or sibling also affected and a positive family history is

particularly useful in diagnosing atopic dermatitis in

infants.

AD is a complex

genetic disease and is often accompanied by other atopic disorders such as

allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, asthma and food allergies. These conditions may

appear simultaneously or develop in succession. AD and food allergy have a

predilection for infants and young children, while asthma favours older

children and rhino-conjunctivitis predominates in adolescents. This

characteristic age-dependent sequence is referred to as the “atopic march”. Atopic

dermatitis is a risk factor for the future development of allergic airways

disease, possibly by percutaneous sensitization to protein antigen. In patients harbouring a

filaggrin mutation has associated clinical features such as ichythosis

vulgaris, keratosis pilaris and hyperlinear palms.

In 2003, a consensus

conference spearheaded by the American Academy of Dermatology suggested revised

Hanifin and Rajka criteria that are more streamlined and applicable to the full

range of patient ages.

|

DIAGNOSTIC FEATURES AND

TRIGGERS OF ATOPIC DERMATITIS (AD) |

|

Essential features:

must be present and are sufficient for diagnosis |

|

Pruritus 1.

·

Rubbing or scratching can initiate or exacerbate flares

(“the itch that rashes”) ·

Often worse in the evening and triggered by exogenous

factors (e.g. sweating, rough clothing) Typical eczematous

morphology and age-specific distribution patterns 2.

·

Face, neck, and extensor extremities in infants and

young children ·

Flexural lesions at any age ·

Sparing of groin and axillae Chronic or

relapsing course |

|

Important features: seen in most cases, supportive of diagnosis |

|

Onset during

infancy or early childhood Personal and/or

family history of atopy (IgE reactivity) Xerosis .

·

Dry skin with fine scale in areas without clinically apparent inflammation; often

leads to pruritus |

|

Associated features: suggestive of the diagnosis, but less

specific |

|

Other filaggrin

deficiency-associated conditions: keratosis pilaris, hyperlinear palms,

ichthyosis vulgaris Follicular

prominence, lichenification, prurigo lesions Ocular findings:

recurrent conjunctivitis, anterior subcapsular cataract; periorbital changes:

pleats, darkening Other regional

findings, e.g. perioral or periauricular dermatitis, pityriasis alba Atypical vascular

responses, e.g. mid facial pallor, white dermographism*, delayed blanch |

|

Triggers |

|

Climate: extremes of

temperature (winter or summer), low

humidity Irritants: wool/rough

fabrics, perspiration, detergents, solvents Infections: cutaneous

(e.g. Staphylococcus aureus, molluscum contagiosum) or

systemic (e.g. URI) Environmental allergies: e.g. to dust

mites, pollen, contact allergens Food allergies: .

·

Trigger in small minority of AD patients, e.g. 10–30%

of those with moderate to severe, refractory AD ·

Common allergens: egg > milk, peanuts/tree nuts,

(shell)fish, soy, wheat ·

Detection of allergen-specific IgE (via blood and skin

prick tests) does not necessarily

mean that allergy is triggering the patient’s AD *Stoking the skin with

blunt instrument leads to white streaks within 1 minute that reflects

excessive vasoconstriction. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DIAGNOSTIC

GUIDELINES FOR ATOPIC DERMATITIS The UK refinement of Hanifin and

Rajka's diagnostic criteria of atopic dermatitis (eczema) In order

to qualify as a case of atopic dermatitis (eczema) with the UK diagnostic

criteria, the child: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Epidemiology

The

current prevalence of AD is approximately 10–30% in children and 2–10% in

adults.

In general, the prevalence of AD in

rural areas and low-income countries is significantly lower than in their urban

and high-income countries. This observation supports the hygiene hypothesis,

which postulates that decreased exposure to infectious agents in early

childhood increases susceptibility to allergic diseases.

Three subsets of AD based on age of onset have emerged from

epidemiologic studies:

|

|

· Early-onset type: defined as AD beginning in the

first 2 years of life and is the most common type of AD. The age of onset is between 2 and 6

months of life in 45% of affected

individuals, during the first year of life in 60%, and before 5 years of age

in 85%. Approximately half of children

with disease onset during the first 2 years of life develop allergen-specific

IgE antibodies by 2 years of age. About 60% of infants and young

children with AD go into remission by 12 years of age, but in others disease

activity persists into adolescence and adulthood. |

|

|

|

|

· Late-onset type: defined as AD that starts after

puberty. Approximately 30% of AD patients overall are in the

non-IgE-associated category, and among adults, the vast majority of such

patients are women. · Senile-onset

type:

an unusual subset of AD that begins after 60 years of age has been identified

more recently. |

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of

AD can be divided into three major categories: (1) epidermal barrier dysfunction; (2) immune dysregulation; and (3) alteration of the microbiome. Each of these can be modulated by

genetic and environmental factors.

Atopic dermatitis results

from defects in epidermal barrier function, immune dysregulation, and

environmental influences.

SC, stratum corneum; KLK, kallikrein; TEWL,

transepidermal water loss; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

Major mechanisms of AD include abnormalities

in the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes that lead to a defective

stratum corneum. A defective barrier in AD allows the penetration of allergens

and microbes, leading to IgE sensitization and type 2 cytokine productions that

drive allergic inflammation. At least two AD subtypes can be distinguished: the

first type is characterized by a strong type 2 mediated responses with high

levels of serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) and the second is a non-allergic type

characterized with normal IgE levels.

T cells and dendritic cells in atopic dermatitis

T cells are moderately increased in the dermis

of non-lesional skin. Skin homing CLA þ T cells display a Th2 profile in early

lesions and in the circulation. However, in the course of the disease,

increasing populations of Th1 cells and IFN-g and sometimes Th17 and Th22 cells

are detected in chronic lesions of AD. IL-33, IL-25 and TSLP released from

keratinocytes directly or indirectly support the type 2 response.

Interleukin-31 (IL-31), preferentially produced from Th2 cells, binds to the

IL-31 receptor (IL-31R) expressed on sensory nerves. IL-31/IL31R signaling has

recently been shown to play a critical role in the development of pruritus in

AD. Three populations of antigen-presenting cells including Langerhans cells

(LCs), monocyte-derived LC-like cells (MDLC), and inflammatory dendritic

epidermal cells (IDECs) exist in the skin. IDECs and LC-like cells have been

found to be present in both steady states and inflammatory states, and they are

present in lesional AD. LC and IDEC in AD skin do not respond to Toll-like

receptor (TLR) 2 activation and may contribute to the inability to clear S.

aureus infection.

Elevated IgE and the inflammatory response

The role of immunoglobulin E

(IgE) in AD is unknown. According

to the current consensus nomenclature by the World Allergy Organization (WAO),

the term “atopy” is tightly linked to the presence of allergen-specific IgE

antibodies in the serum against inhalants or food allergens in 70% of AD

patients, as documented by positive fluorescence enzyme immunoassays

(previously radioallergosorbent [RAST] tests) or skin prick tests. Thus, an IgE-associated

or allergic form of atopic dermatitis is also known as extrinsic AD).

The remaining 30% of AD patients who has

normal total serum IgE levels (no evidence of IgE-sensitization against

inhalants or food allergens) is categorized as having a non-IgE-associated

or non-allergic form of dermatitis (also known as intrinsic AD). The levels of IgE do not necessarily correlate with the

activity of the disease; therefore elevated serum IgE levels can only be

considered supporting evidence for the disease. Total IgE level is

significantly higher in children with coexistent atopic respiratory disease in

all age groups. Most persons with AD have a personal or family history of

allergic rhinitis or asthma and increased levels of serum IgE antibodies

against airborne or ingested protein antigens. AD usually diminishes during the

spring hay fever season, when aeroallergens are at maximum concentrations.

Intrinsic vs Extrinsic Atopic Dermatitis

Patients with intrinsic AD do not have elevated IgE levels

and filaggrin (FLG) mutation, often begins in adulthood and the immune system

exhibits Th 22 and Th 17 activation. Patients with extrinsic AD have elevated

IgE levels and filaggrin (FLG) mutation, early onset AD and Th 2 dominant the

immune response.

|

|

Intrinsic (non-allergic) |

Extrinsic (allergic) |

|

Physical exam |

comparable

|

comparable

|

|

Frequency of AD |

~25%

|

~75%

|

|

Family history |

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Age of onset |

Late

|

Early

(childhood) |

|

Association with other atopic disease (asthma, hay fever) |

Rare

|

Common

|

|

Serum IgE level |

Normal

|

High

|

|

Skin prick tests or RAST to |

Negative

|

Positive

|

|

Foods & aeroallergens |

|

|

|

Cytokine profile |

|

|

Blood eosinophilia

Eosinophils may be major effector

cells in AD. Blood eosinophil counts roughly correlate with disease severity,

although many patients with severe disease show normal peripheral blood

eosinophil counts. Patients with normal eosinophil counts mainly are those with

atopic dermatitis alone; patients with severe atopic dermatitis and concomitant

respiratory allergies commonly have increased concentrations of peripheral

blood eosinophils. There is no accumulation of tissue eosinophils; however,

degranulation of eosinophils in the dermis releases major basic protein that

may induce histamine release from basophils and mast cells and stimulate

itching, irritation, and lichenification.

Clinical features

Skin Symptoms Pruritus is the sine qua non of atopic dermatitis— “eczema is

the itch that rashes.” The constant scratching leads to a vicious cycle of itch

→ scratch → rash

→

itch → scratch.

Pruritus

Intense pruritus is a hallmark of AD. The itch may be

intermittent throughout the day but often worse in the early evening and night

and may be exacerbated by warmth, bathing, emotional upset, exposure to irritants and allergens, changes in humidity and

excessive sweating. Pruritus may also

flares after

taking off clothing. Wool is an

important trigger; wool clothing or blankets directly in contact with skin

(also wool clothing of parents, fur of pets, carpets). The consequences of pruritus are rubbing and scratching,

prurigo papules, lichenification and eczematous skin lesions, explaining why AD

is known as the “itch that rashes”. Excoriations (linear or punctate) are

frequently present, providing evidence of scratching. Instead of scratching causing pain, in the atopic patient the “pain”

induced by scratching is perceived as itch and induces more scratching. The

scratching impulse is beyond the control of the patient. Control of pruritus is important because mechanical injury

from scratching can induce release of pro inflammatory cytokine and chemokine,

leading to a vicious scratch-itch cycle perpetuating the AD skin rash. Since

classic antihistamines are ineffective in AD, it is assumed that this mediator

histamine does not have a crucial role in AD-related pruritus. In contrast,

stress-induced neuropeptides, proteases, kinins, and T cell derived cytokines

such as interleukin (IL)-31 are known to induce itch. IL-31 is strongly

pruritogenic and exerts its biologic activity through a receptor composed of

the IL-31 receptor A and oncostatin M receptor β protein, both of which are

over expressed in lesional skin of AD. These findings imply that IL-31 has an

important role in the pruritus of AD.

*May be the only manifestation of AD in adults.

†Not to be

confused with nummular eczema occurring outside the setting of AD.

Disease Course

AD has a broad

clinical spectrum that varies depending upon the age of the patient. It is divided into infantile, childhood and adolescent/adult

stages. In each stage, patients may develop acute, subacute and chronic eczematous

lesions. In all stages, pruritus is the hallmark feature and

often precedes the appearance of skin lesions; hence the concept that AD is

“the itch that rashes.”

Acute lesions predominate in infantile AD and are characterized by edematous,

erythematous papules and plaques that may exhibit vesiculation, oozing and

serous crusting. Subacute dermatitis is characterized by erythematous,

scaling papules and variable crusting. Chronic lesions, which typify adolescent/adult AD, present as (1) thickened plaques of skin, (2)

accentuated skin markings (lichenification), and (3) fibrotic papules (prurigo nodularis).

Perifollicular accentuation

(follicular eczema) and small, flat-topped papules (papular eczema) are

particularly common in individuals with darkly pigmented skin. In any stage of

AD, patients usually have dry, lackluster skin and the most severely affected

individuals may evolve to a generalized exfoliative erythroderma. All types of

AD lesions can leave post inflammatory hyper-, hypo- or (in more severe cases)

depigmentation upon resolution.

Infantile

AD (age 2 months to

2 years) typically develops after the second month of life. The

lesions most frequently start on the face, but may occur anywhere on the skin

surface, often initially appearing as erythema edematous papules and papulovesicles on the cheeks (often

sparing the central face), which may evolve to form large plaques with oozing

and crusting.

The face (especially around the mouth) and neck are affected in over 90 % of

infants. Secondary infection and lymphadenopathy are common. The eruption may extend to the scalp, neck, forehead, wrists, and

extensor aspects of the extremities and trunk

in

scattered, ill-defined, often symmetrical patches. Young infants may attempt to relieve itch through rubbing

movements against their bedding, whereas older infants are better able to

directly scratch affected areas. The areas involved

correlate with the capacity of the child to scratch or rub the site, and the

activities of the infant, such as crawling. By 8 to 10 months of

age, the exposed surfaces, especially the extensor aspect of the elbows and

knees often show dermatitis, perhaps

because of the role of friction associated with crawling and the exposure of

these sites to irritant and allergenic triggers such as those found in carpets.

Typically, lesions of AD spare the groin and diaper area during infancy, which

aids in the diagnosis. This sparing likely reflects the combination of

increased hydration in the diaper area, protection from triggers by the diaper,

and inaccessibility to scratching and rubbing. The disease runs a chronic,

fluctuating course, varying with such factors as teething, respiratory

infections, emotional upsets and climatic changes. Partial remission may occur during the summer, with relapse in winter.

This may relate to the therapeutic effects of ultraviolet (UV) B and humidity

in many atopic patients, and the aggravation by wool and dry air in the winter.

The infantile pattern of AD usually disappears by the end of the second year of

life.

Childhood AD (age 2 to 12 years), the childhood phase of AD usually occurs from 2 years of age to puberty. It resembles the infantile form early on, but later on evolves into features seen in the adulthood form. Affected persons in this age group are less likely to have exudative and crusted lesions and have a greater tendency toward chronicity and lichenification. Eruptions are characteristically drier and more papular and the erythematous and edematous papules tend to be replaced by indurated circumscribed scaly plaques. From 18 to 24 months onwards, the sites most characteristically involved are flexural areas (i.e., the antecubital and popliteal fossae, flexor wrists, sides of the neck, and front of ankles). These areas of repeated flexion and extension perspire with exertion. The act of perspiration stimulates burning and intense itching and initiates the itch-scratch cycle. Tight clothing that traps heat about the neck or extremities further aggravates the problem. Inflammation typically begins in one of the fossae or around the neck. The rash may remain localized to one or two areas or progress to involve the neck, antecubital and popliteal fossae, wrists, and ankles. The eruption begins with papules that rapidly coalesce into plaques, which become lichenified when scratched. The border may be sharp and well-defined, as it is in psoriasis, or poorly defined with papules extraneous to the lichenified areas. A few patients do not develop lichenification even with repeated scratching. The sides of the neck may show a striking reticulate pigmentation, sometimes referred to as ‘atopic dirty neck’. Facial involvement switches from cheeks and chin to periorbital and perioral, the latter sometimes manifesting as “lip-licker’s dermatitis”. Nail dystrophy may be seen when fingers are affected, indicating involvement of the nail matrix. AD often subsides as the patient grows older; leaving an adult with skin that is prone to itching and inflammation when exposed to exogenous irritants.

Severe AD

involving a large percentage of the body surface area can be associated with

growth retardation.

Adult/adolescent

AD (age >12 years) also features subacute to chronic,

lichenified lesions, and involvement of the flexural folds typically continues.

However, the clinical picture may also change. The adult phase of AD begins

near the onset of puberty. The reason for the resurgence of inflammation at

this time is not understood, but it may be related to hormonal changes or to

the stress of early adolescence. Most adolescents and

adults with AD will give a history of childhood disease and those patients who have suffered from continuous AD

since childhood are more likely to have extensive or even erythrodermic

disease.

One area or several

areas may be involved, and there are several characteristic patterns.

Inflammation

in flexural areas

This pattern

is commonly seen and is identical to childhood flexural inflammation.

Hand

dermatitis

Atopic

hand eczema affects

approximately 60% of adult patients with AD and may be the only manifestation

of the condition. Patients with AD often develop nonspecific, irritant hand

dermatitis.

Adults are exposed to

a variety of irritating chemicals such as harsh soaps, detergents, and

disinfectants in the home and at work, and they wash more frequently than do

children. It is extremely common for atopic hand dermatitis to

appear in young women after the birth of a child, when increased exposure to irritants

like soaps and water triggers their disease. Contact allergy may manifest as

chronic hand eczema as they are frequently exposed to preservatives and other

potential allergens in the creams and lotions that are continually applied to

their skin because of their dry skin.

Atopic hand

eczema typically involves one or both the volar wrists and dorsum of the

hands as well as palmar surfaces. Irritation causes redness and scaling on the

dorsal aspect of the hand or around the fingers. Itching develops, and the

inevitable scratching results in lichenification or oozing and crusting. A few

or all of the fingertip pads may be involved and become dry and peeling or red

and fissured. The eruption may be painful, chronic, and resistant to treatment.

The palms and sides of the fingers may develop the deep-seated vesicles of dyshidrotic

eczema. Involvement of the feet is also common and almost half the

patients with atopic hand eczema will have eczema on the feet.

Inflammation

around eyes

The lids are thin, frequently exposed to irritants, and easily traumatized by scratching. Many adults with AD have inflammation localized to the upper lids. In general, the involvement is bilateral and the condition flares with cold weather. Habitual rubbing of the inflamed lids with the back of the hand is typical. In contrast to eyelid eczema due to other causes, it is characterized by lichenification of the periorbital skin. As in hand dermatitis, irritants and allergic contact allergens must be excluded by a careful history and patch testing.

Lichenification

of the anogenital area

Lichenification

of the anogenital area is probably more common in patients with AD than in

others. Intertriginous areas that are warm and moist can become irritated and

itch. Lichenification of the vulva, scrotum, and perianal area may develop with

habitual scratching. These areas are resistant to treatment and inflammation

may last for years. The patient may delay visiting a physician because of

modesty, and the untreated lichenified plaques become very thick. Emotional

factors should also be considered with this isolated phenomenon.

Adults

frequently complain that flares of AD are triggered by acute emotional upsets

such as anxiety, and depression.

Even in

patients with AD in adolescence and adulthood, improvement usually occurs over

time, and dermatitis is uncommon after middle life. In general, these patients

retain mild stigmata of the disease, such as dry skin, easy skin irritation,

and itching and also susceptible to a flare of their disease when exposed to

the specific allergen and in response to heat and perspiration.

Senile AD (age >60

years) is

characterized by marked xerosis. Most of these patients do not have the

lichenified flexural lesions typical of AD in children and younger adults.

Regional Variants of Atopic Dermatitis

Face The

face is a frequent location for site-specific manifestations. Eczema of the

lips, referred to as cheilitis sicca, is common in AD patients,

especially during the winter. It is characterized by dryness (“chapping”) of

the vermilion lips, sometimes with peeling and fissuring, and may be associated

with angular cheilitis. Patients try to moisten their lips by licking, which in

turn may irritate the skin around the mouth, resulting in so-called lip-licker's

eczema. Frequently spreading some distance around the mouth, it

may become secondarily infected and crusted. Its persistence, and perhaps its

origin, is attributable to habits of lip licking, thumb sucking, dribbling or

chapping. It is easily transformed into true perioral dermatitis by the

application of potent corticosteroids. The regular application of 1%

hydrocortisone ointment is usually most helpful. Contact sensitivity, for

example to toothpaste ingredients, can occasionally be demonstrated.

Another common feature of childhood AD is ear eczema,

presenting as erythema, scaling and fissures under the earlobe and in the

retroauricular area, sometimes in association with bacterial superinfection and

this infra-auricular

fissures appears to be quite specific to atopic dermatitis.

“Head and neck dermatitis” represents a variant of AD that typically occurs after

puberty and primarily involves the face, scalp and neck. It is postulated that

lipophilic Malassezia yeasts, members of the normal skin flora that

colonize the head and neck area, represent an aggravating factor for this

condition. Serum levels of M. furfur-specific IgE have been shown to

correlate with the severity of head and neck dermatitis, and improvement with

systemic antifungal treatment has been observed in some patients.

Eczema variants also occur in acral sites.

Juvenile plantar dermatosis presents with “glazed” erythema, scale and fissuring on the

balls of the feet and plantar aspect of the toes in children with AD,

especially during the winter.

The prurigo form of AD favours the extensor

aspects of the extremities and is characterized by firm, dome-shaped papules

and nodules with central scale-crust, similar to prurigo nodularis lesions in

non-atopic patients.

Nummular lesions also tend to develop on the extremities in children and

adults with AD, appearing as coin-shaped eczematous plaques, usually 1 to

3 cm in diameter and often with prominent oozing and crusting (similar to nummular

dermatitis lesions in non-atopic patients). Colonization with Staphylococcus

aureus is thought to represent a trigger for this type of eczema. Intense

pruritus is a feature of both prurigo and nummular lesions. Frictional

lichenoid eruption has a predilection for atopic children (especially

boys) and presents as multiple small, flat-topped, pink to skin-colour papules

on the elbows and (less often) knees and dorsal hands. Lastly, localized

patches of atopic dermatitis can occur on the nipples, nipple eczema especially in

adolescent and young women.

The

pattern of atopic eczema varies with age. It may clear at any stage.

Associated features of

atopic dermatitis (“atopic stigmata”)

|

Xerosis |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Ichthyosis

vulgaris |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Keratosis

pilaris |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Palmar

and plantar hyperlinearity |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Dennie–Morgan

lines |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Periorbital

darkening (“allergic shiners”) |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Anterior

neck folds |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Hertoghe

sign |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

White

dermographism |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Follicular

prominence |

|

||||||||||||||||||

Cutaneous stigmata

A linear

transverse fold just below the edge of the lower eyelids, known as the

Dennie–Morgan fold, is widely believed to be indicative of the atopic

diathesis, but may be seen with any chronic dermatitis of the lower lids. In

atopic patients with eyelid dermatitis, increased folds and darkening under the

eyes is common. When taken together with other clinical findings, they remain

helpful clinical signs. A prominent nasal crease may also be noted.

Dry

skin

The skin of atopic

individuals has been shown to be deficient in ceramides, filaggrin, and natural

moisturizing factors, leading to increased transepidermal water loss and

epidermal microfissuring. The less

involved skin of atopic patients is frequently dry, scaly and slightly

erythematous. Histologically, the apparently normal skin of atopics is

frequently inflamed subclinically and this dry, scaling skin of AD may

represent low grade dermatitis. Filaggrin is processed by caspase 14 during terminal

keratinocyte differentiation into highly hydroscopic pyrrolidone carboxylic

acid and urocanic acid, collectively known as the “natural moisturizing factor”

or NMF. Null mutations in FLG lead to reduction in NMF, which probably contributes

to the xerosis that is almost universal in AD. Transepidermal water loss (TEWL)

is increased through an abnormal stratum corneum, which

may also correlate with disease activity. This

may be caused by of abnormal ceramide and sphingosine

synthesis. The defective lipid bilayers

that result retain water poorly, leading to increased TEWL and clinical

xerosis.

Pityriasis alba

It frequently affects children and adolescents with AD. It

is characterized by multiple ill-defined hypo pigmented macules and patches

with fine scaling, which are typically located on the face (especially the cheeks)

but occasionally appear on the shoulders and arms. These lesions are most

obvious in individuals with darkly pigmented skin and/or following sun exposure.

Pityriasis alba is a low-grade eczematous dermatitis that disrupts the transfer

of melanosomes from melanocytes to keratinocytes. It usually responds

to emollients and mild topical steroids, preferably in an ointment base.

Keratosis

pilaris (KP)

Horny

follicular papules of the outer aspects of the upper arms, thighs, cheeks, and

buttocks, are commonly associated with AD. The keratotic papules on the face may

be on a red background, a variant of KP called keratosis pilaris rubra facei.

KP is often refractory to treatment. Moisturizers alone are only partially

beneficial. Some patients will respond to topical lactic acid or urea.

Thinning of

the lateral eyebrows, Hertoghe’s sign is sometimes present. This apparently

occurs from chronic rubbing due to pruritus and subclinical dermatitis.

Vascular stigmata

Atopic

individuals often exhibit perioral, perinasal, and periorbital pallor

(“headlight sign”). White dermatographism is blanching of the skin at the site

of stroking with a blunt instrument. This reaction differs from the triple

response of Lewis, in that it typically lacks a wheal, and the third response

(flaring) is replaced by blanching to produce a white line.

Atopics are at

increased risk of developing various forms of urticaria, including contact

urticaria. Episodes of contact urticaria may be followed by typical eczematous

lesions at the affected site.

Complications

Psychosocial

aspects

Atopic dermatitis has

a profound effect, equal to or greater than that of asthma and diabetes, on

many aspects of patients’ lives and the lives of their families. In children,

the most troublesome symptoms are itching, distress at bath time and difficulty

going to sleep. This can lead to behavioural difficulties and school

performance in severely affected children.

Infections

Infections/Agents associated with atopic dermatitis

Patients with AD are predisposed to the development of skin

infections because of factors including an impaired skin barrier and modified

immune milieu. Bacterial and viral infections represent the most common

complications of AD.

Bacterial

infections

Considering that S. aureus colonizes the skin of the

vast majority of patients with AD, it is not surprising that impetiginization

(which can also occur due to Streptococcus pyogenes) occurs quite

frequently. Bacterial infections may also exacerbate AD by stimulating the

inflammatory cascade, e.g. via S. aureus exotoxins that act as

super antigens. The importance of S. aureus colonization in AD is supported by the observation that

patients with severe AD, even those without overt infection, can show clinical

response to combined treatment with anti-staphylococcal antibiotics and topical

glucocorticoids. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus has become an increasingly

important pathogen in patients with AD.

Indeed, any acute

vesicular eruption in an atopic should suggest the diagnosis of secondary

bacterial or viral infection.

Viral

infections

Patients with atopic

dermatitis, both active and quiescent, are liable to develop acute generalized

infections with herpes simplex virus (eczema herpeticum), to produce the

clinical picture of Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption. Such episodes may present

as a severe systemic illness with high fever and a widespread eruption.

However, there may be no systemic disturbance, and at times the eruption may be

quite localized, often to areas of pre-existing atopic dermatitis.

After an

incubation period of 5-21 days, multiple, itchy, vesiculo-pustular lesions

erupt in a disseminated pattern; vesicular lesions are umbillicated, tend to

crop and often become hemorrhagic and crusted which result in numerous

monomorphic, extremely painful and punched-out erosions. These erosions may

coalesce to large, denuded, and bleeding areas that can extend over the entire

body. Eczema herpeticum is frequently widespread and may occur at any site,

with a predilection for the head, neck and trunk. Complications may include

superinfection with S. aureus or S. pyogenes as well as herpetic

keratoconjunctivitis and meningoencephalitis. Patients with mutations in the

filaggrin gene and those who have both severe AD and asthma have an increased

risk for eczema herpeticum, and decreased production of antimicrobial peptides

may have a pathogenic role. Patients with AD are also predisposed to the

development of widespread molluscum contagiosum, sometimes with

several hundred lesions. Individuals with AE have a higher incidence

of common warts.

Superficial fungal infection

Superficial

fungal infections are also more common in atopic individuals and may

contribute to the exacerbation of AD. Patients with AD have an increased

prevalence of Trichophyton rubrum infections compared to non atopic controls.

There has been particular interest in the role of M. sympodialis (Pityrosporum ovale

or P. orbiculare) in AD. M. sympodialis is lipophilic yeast commonly present in

the seborrheic areas of the skin. IgE antibodies against M. furfur are commonly

found in AD patients and most frequently in patients with head and neck

dermatitis. The potential importance of M. sympodialis as well as other

dermatophyte infections is further supported by the reduction of AD skin

severity in such patients after treatment with antifungal agents.

Ocular complications

Besides development of acute conjunctivitis as a component

of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, the atopic eye disease also includes chronic

manifestations such as atopic keratoconjunctivitis (typically in adults) and

vernal keratoconjunctivitis (favors children living in warm climates). Atopic

keratoconjunctivitis is usually bilateral and symptoms include ocular itching,

burning, tearing and copious mucus discharge, often in association with

conjunctival injection and blepharitis that manifests as swelling and scaling

of the eyelids. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis is a severe bilateral recurrent

chronic inflammatory process associated with papillary hypertrophy or

cobblestoning on the upper palpebral conjunctiva. Keratoconusis an uncommon finding, occurring in approximately 1% of atopic

patients, is a conical deformity of the cornea

believed to result from chronic rubbing of the eyes in patients with atopic allergic

rhinoconjunctivitis. It is due to a degenerative change in the

cornea, which is forced outwards by the intraocular pressure, giving rise to

marked visual disturbances. Up to 10% of patients with AD

develop cataracts, either anterior or posterior, with anterior cataracts more specifically related to AD and

posterior cataracts occurring more commonly. Posterior

subcapsular cataracts in atopic individuals are indistinguishable from

corticosteroid-induced cataracts. Development of cataracts is more common in patients

with severe dermatitis and its peak incidence is between 15 and 25 years

of age. It is almost always bilateral. Cataract associated with AE is thought

to arise due to a combination of rubbing and the use of topical steroids.

Asthma and allergic rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and asthma

occur in 30–50% of cases of AE. The age of onset is usually later than that of

the eczema. AE is a risk factor for the future development of allergic airways

disease, possibly by percutaneous sensitization to protein antigen through an

abnormal cutaneous barrier: the ’atopic march’.

Exfoliative Dermatitis

Patients with extensive skin involvement may develop exfoliative dermatitis. This is associated with generalized redness, scaling, weeping, crusting, lymphadenopathy, and fever. Although this complication is rare, it is potentially life threatening. It is usually due to superinfection, for example, with toxin-producing S. aureus or herpes simplex infection, continued irritation of the skin, or inappropriate therapy. In some cases, the withdrawal of systemic glucocorticoids used to control severe AD may be a precipitating factor for exfoliative erythroderma.

Diagnostic criteria

Major features in the

diagnostic criteria include pruritus, eczematous skin lesions in typical

age-specific distribution patterns, a chronic or chronically relapsing course,

early age at onset, and a personal and/or family history of atopy. Atopic

stigmata, especially xerosis, are also recognized as supporting features.

IgE-associated and non-IgE-associated AD are distinguished based on the

evaluation of total serum IgE levels (elevated in the former; normal

<150 IU/ml) and the presence or absence of specific IgE.

Histology

The histologic

features of AD depend upon the stage of the lesion sampled. Acute, exudative eczema is characterized by marked

spongiosis, with intraepidermal fluid collection leading to the formation of

vesicles (micro and macro) or even bullae. Some dermal edema may also be

present, together with perivascular lymphocytes that extend into the epidermis

and a variable number of eosinophils. In subacute lesions,

vesiculation is absent whereas acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis

become evident. In chronic, lichenified

AD, epidermal thickening is more pronounced in a pattern that may be either

irregular or regular (psoriasiform). Changes in the granular layer vary from

thickening secondary to rubbing, as seen in lichen simplex chronicus, to

thinning when there is a psoriasiform pattern, seen in some nummular lesions.

Spongiosis and inflammation are less conspicuous, but there may be an increased

number of mast cells and dermal fibrosis.

These features are not specific,

as similar findings are observed in other eczematous dermatoses such as

allergic contact dermatitis. There are occasionally histologic clues to the

aetiology, such as individually necrotic keratinocytes that suggest an irritant

contact dermatitis. However, a skin biopsy is usually more helpful in excluding

other entities that can mimic AD clinically, such as mycosis fungoides.

Differential Diagnosis

In infants, AD is

often preceded and/or accompanied by seborrheic dermatitis, which commonly

presents during the first month of life as yellowish-white, adherent

scale-crusts on the scalp. Infantile seborrheic dermatitis also has a

predilection for skin folds (where lesions may be oozing and lack scale) and

the forehead, in contrast to the typical distribution of infantile AD on the

extensor surfaces of the extremities and cheeks as well as the scalp. Scabies

in infants often has generalized involvement and can mimic AD; in addition to

the presence of burrows or identification of the mite or eggs (e.g. via

dermoscopy or skin scrapings), scabies can usually be distinguished by the

predominance of discrete small crusted papules, involvement of the axillae and

diaper area, and the presence of acral vesiculopustules.

Adolescents

and adults without a personal or family history of atopy who present with an

eczematous eruption should have a thorough history and consideration of patch

testing to assess for allergic contact dermatitis. This diagnosis should also

be considered in children and adults with established AD who fail to respond as

expected to treatment or who develop lesions in an atypical distribution

pattern. Components of emollients or topical corticosteroid preparations

represent potential allergens in these individuals. Protein contact dermatitis

has a predilection for atopic individuals and can also present as a chronic

eczematous dermatitis. Causes include a variety of foods and animal products,

and it is diagnosed by prick testing or observation of an urticarial reaction

within 30 minutes of patch testing on previously affected skin.

Laboratory testing is not needed in the routine

evaluation and treatment of uncomplicated AD. Estimation of total serum IgE,

specific radio allergosorbent tests (RASTs) and prick tests usually serve only

to confirm the atopic nature of the individual.

Serum IgE levels are

elevated in approximately 70–80% of AD patients. This is associated with

sensitization against inhalant and food allergens and/or concomitant allergic

rhinitis and asthma. In contrast, 20–30% of AD patients have normal total IgE

levels and negative RASTs, whereas 15% of apparently healthy individuals have a

raised serum IgE levels. This subtype of AD has a lack of IgE sensitization

against inhalant or food allergens. It may be that skin prick test positivity

to food allergens in young children with severe atopic dermatitis and a high

serum IgE indicates a high risk of developing later allergic respiratory

disease. The majority of patients with AD also have peripheral blood

eosinophilia.

Prognosis

The following predictive factors correlate

with a poor prognosis for AD: widespread AD in childhood associated allergic

rhinitis and asthma, family history of AD in parents or siblings, early age at

onset of AD, being an only child, and children with raised IgE antibodies to foods

and inhalant antigens at 2 years of age.

Measuring the severity of atopic

dermatitis

The severity

of dermatitis can be measured and monitored in several ways. The SCORing Atopic

Dermatitis (SCORAD) index, the Objective Severity Assessment of Atopic

Dermatitis (OSAAD) and the Three Item Severity Scoreall have merit in a

research context, but are not practical for daily clinical use.

The severity

assessment has been simplified with the objective to stratify treatment

accordingly in individual patients.

- Measuring the area involved in

percentage of body surface, where 1% body surface approximates the size of

one of the patient's hands (including the fingers).

- Establishing acute, subacute or

chronic changes, where acute changes would imply more severe dermatitis.

- Determining the impact on the

patient's quality of life (e.g. sleep disturbances, absenteeism, visible

scratch marks and social withdrawal).

Dermatitis

can then be classified and treated as mild, moderate or severe as outlined

below.

Treatment

Because

AD is a chronic relapsing disease, the classic approach to therapy is targeting

acute flares with short-term treatment regimens, i.e. reactive management.

Based on recent insights into the underlying skin barrier defect and its

relationship to inflammatory processes in the skin and other organs, a

proactive approach that includes long-term maintenance therapy is now recommended.

This treatment strategy may modify the overall disease course and possibly

prevent the development of atopic comorbidities. Management of AD includes

education of patients/parents, gentle skin care, moisturizer use, and

anti-inflammatory therapy to control subclinical inflammation as well as overt

flares. Topical agents represent the mainstay of treatment. Severe disease may require

phototherapy or systemic medications, usually in conjunction with continued

topical therapy. Factors that can potentially exacerbate AD including

irritants, relevant allergens and microbial agents should be

identified and, if possible, avoided.

B. Intermittent courses of a systemic corticosteroid result

in rebound flares and worsening of disease over time. In contrast, a proactive

regimen utilizing topical corticosteroid leads to longer clear periods and

milder disease over time. TCI, topical calcineurin inhibitor.

General care

Education (patients and parents)

Patient and parent education is effective in the

management of AD and should aim to provide information about the clinical

characteristics of AD (aetiology, clinical manifestations, and disease course

in common person language), aggravating and relieving factors, self-management

and improving coping skills. Parents often seek an eradicable

cause for their child’s AD and have difficulty accepting “control” rather than

a “cure” for the condition.

Education of patient or caregiver is highly

recommended at each consultation in the management of AD and should encompass:

a. appropriate treatment doses and application frequency; b. how to step up or

step down treatment; c. skin care and bathing; d. management of infection. This

leads to more effective management of AD and should be reinforced at every

consultation.

Bathing

Bathing and showering are important not only for

hydration of the skin and for washing away the components of perspiration but also for

washing away allergens, such as, dust and pollens, scale,

irritants and microbes on the

skin surface. Bathing also allows removal of dirt and debris from the skin and

thereby reduces the chance of infection. Swimming should be avoided in acute

flares as the amount of free residual chlorine may impact the skin barrier and

contribute to AD exacerbation.

It is

generally recommended that patients bath or shower once daily with lukewarm

water (27 degree Celsius to 30 degree Celsius), which is not too hot and not

too cold, for a short period of time (e.g., 5 to 10 min). Although allowing

moisture to fully evaporate from the skin following bathing can worsen xerosis,

application of an emollient to the skin within 3 minutes of exiting a daily

lukewarm bath increases skin hydration and barrier function. If treatment with

a topical corticosteroid or other anti-inflammatory agent is needed, it should

be applied immediately after bathing, prior to the moisturizer. For acute

flares of AD, 10- to 20-minute soaks in lukewarm or tap water compresses

followed directly with corticosteroid application (“soak and smear”) this has

been referred to as the “soak and smear” technique.

Bubble

baths and scented oils should be avoided. Scalp care should include a bland

shampoo.

Cleansing

The skin must be cleansed thoroughly, but gently

and carefully to get rid of crusts and bacterial contaminants in case of

bacterial super infection. Strong scrubbing or rubbing immediately after bath

should be avoided. Skin should be dried using soft towels.

Use of non-soap cleansers (e.g., Syndet) that

are neutral to low pH, hypoallergenic, non-irritant and fragrance free is

recommended for AD.

Moisturizers/

emollients

As there

is impaired skin barrier in the pathogenesis of AD, daily use of moisturizers

constitutes the core of the management of AD. Continuous basic therapy with

emollients is also required even in periods and sites in which the AD is not

active. It should be part of all

treatment phases; mild, moderate, and severe. A

moisturizer repairs the skin barrier, maintains skin integrity and appearance,

reduces transepidermal water loss, and restores the lipid barrier's ability to

attract, hold, and redistribute water; thereby it can reduce xerosis, pruritus,

erythema, fissuring, and lichenification. They make topical

corticosteroids more effective and reduce the quantities required. The regular use of moisturizer has short and

long term steroid-sparing effects in mild to moderate AD and in preventing AD

flares.

Standard

moisturizers contain varying amounts of emollient agents that lubricate the

skin, occlusive agents that prevent water loss, and humectants that attract

water. Preparations should be free of dyes, fragrances, food-derived allergens

such as peanut protein, and other potentially sensitizing ingredients such as

perfumes, lanolin and herbal extracts. The formulation of the emollient should

be chosen based upon the degree of dryness of the skin, the sites of

application, acceptance by the patient and the season. Ointments (e.g.

petrolatum) contain higher concentrations of lipids, have occlusive properties,

and are typically preservative-free; although they tend to cause less stinging

when applied to inflamed skin. However, the greasiness of an ointment is not

acceptable to all patients. Creams may be a more acceptable option for such

individuals, whereas lotions contain higher water content and are not ideal for

the xerosis of AD. The addition of moisturizing factors that is able to bind

water (e.g. glycerol, urea) leads to increased hydration of the epidermis;

although with higher concentrations of urea or α-/β-hydroxy acids, which can decrease scaling, may sting

when used in children and on acutely inflamed or excoriated skin.

Emollients should be applied twice daily to the entire cutaneous

surface.

Persistent

use of emollients when the inflammation is in remission may reduce the time to

and frequency of flares.

In order to identify the emollient that best suits an

individual, it may be useful to provide small quantities of several agents, so

that they may choose which they prefer. Although no

clinical trials have studied the proper amount or frequency of moisturizer use

in patients with AD, moisturizer should be used at least twice daily and more

frequently during acute flare-ups. A generous quantity (150–250 g/week

for young children and 500 g/week for older children and adults) should be

prescribed to encourage their frequent use throughout the day. It is recommended to use moisturizer within 3 min after

taking a bath while the skin is still moist.

Prescription emollient devices

(PEDs) that aim to improve the defective skin barrier of AD include

preparations that contain specific ratios of lipids (e.g. cholesterol, fatty

acids, and ceramides), palmitoylethanolamide, glycyrrhetinic acid, and other

hydrolipids. There is currently no evidence that these agents are superior to

over-the-counter preparations.

STEPLADDER

TREATMENT IN ATOPIC DERMATITIS

Depending on the severity of the AD, topical

treatment methods and/or systemic treatments are recommended. It is recommended

to implement stepladder treatment appropriate to the clinical severity. Once

remission is achieved, it is advisable to shift to proactive maintenance

therapy to reduce the number of subsequent flare ups.

Topical corticosteroids

Topical

corticosteroids represent first-line pharmacologic therapy for AD who has

failed good skin care, including moisturizer use. These agents have

anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, immunosuppressive, and vasoconstrictive

actions, with effects on cutaneous T cells, macrophages, and dendritic

cells. Topical corticosteroids are used

to treat acute flares of AD and as maintenance therapy to prevent relapse.

Efficacy: RCTs have demonstrated safety and

continued efficacy of repeated courses of low- to mid-potency TCS on active AD

skin until clearance for up to 5 years in children and up to 1 year in adults.

Long-term

proactive TCS: The proactive approach of applying low–mid potency TCS twice

weekly for the prevention of flares in stabilized AD has been shown to be

effective in both adults and children.

Long-term TCS adverse effects: When used cautiously, long-term use of low

to mid potency TCS is reasonably safe. However, the long term use of TCS,

especially if high potency may cause local side effects, such as, striae

rubrae, skin atrophy, telangiectasia, skin burning, erythema and acneiform

eruptions. In rare cases, systemic effects may occur including

hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression, more frequently in children

due to the high ratio of total body surface area to body mass, which is about

2.5 to 3 times higher than for adults. The use of twice-weekly proactive

treatment has not been shown to cause skin atrophy.

Frequency of

application: Twice daily application of TCSs is generally recommended for

the treatment of AD; however, evidence suggests that once

daily treatment in the evening, with morning application of emollients, may be

as effective as twice daily corticosteroid treatment. Proactive, intermittent

use of TCSs as maintenance therapy (one to two times per week) on areas that

commonly flare is recommended to help prevent relapses and is more effective

than use of emollients alone.

Topical

corticosteroids designed to have decreased systemic bioavailability and a favourable

therapeutic index (e.g. fluticasone propionate, mometasone furoate) may be

preferable, especially for infants and young children with widespread

involvement.

Factors in

selecting the potency and vehicle of the topical corticosteroid include the

location, type (e.g. acute versus chronic), thickness and extent of the AD

lesions; patient age and preference as well as the cost and availability of

different preparations represent additional considerations. The corticosteroid

should have an appropriate potency to quickly gain control of the flare, and

continuation of daily therapy until the active dermatitis is completely clear

minimizes the likelihood of a rebound. Long-term daily use of an inadequately

potent topical corticosteroid can result in a greater risk of side effects (as

well as less control of the eczema) than relatively brief use of a more potent

agent. After clinical resolution of longstanding or severe lesions, tapering to

every-other-day treatment may be considered prior to decreasing to maintenance

therapy. For children and adults with moderate to severe AD, the risk of

relapse can be significantly reduced by proactive maintenance with twice-weekly

application of a mid-potency topical corticosteroid to the usual areas of

involvement (“hotspots”) when clear (in conjunction with emollient

use), with no evidence of cutaneous atrophy after up to a year of treatment.

For the

face and body folds, high-potency corticosteroids should be avoided if possible

due to risk of cutaneous atrophy and (for the face) acneiform eruptions.

However, short-term use of a potent agent (e.g. mometasone furoate ointment)

may be required to clear thick, exuberant lesions on the cheeks of infants. Potent

corticosteroids (e.g. class 1–2) are often needed for thick or lichenified

plaques, nummular or prurigo-like lesions, and eczema on the palms and soles.

Flurandrenolide tape represents another option for prurigo-like lesions, since

it physically blocks scratching and rubbing of the affected area.

Corticosteroid ointments (which minimize burning/stinging) are generally

preferred considering the dryness of the skin in AD patients and the emollient

effects of these vehicles. Application immediately after bathing improves

cutaneous penetration and also decreases burning. Corticosteroid solutions or

foams represent choices for AD on the scalp. Corticosteroid‐resistant

or infected or crusted dermatitis may respond better to steroid/antibiotic

combinations.

Systematic

reviews have concluded that topical corticosteroids have a favorable safety

profile with short-term (up to several weeks) daily use and long-term

intermittent use. However, “steroid phobia” is very common among AD patients

and their parents, and it often leads to delayed and inadequate treatment. It

is essential that these fears and incorrect beliefs regarding topical

corticosteroids are addressed to ensure adherence to the treatment plan.

When AD

does not respond as expected to topical corticosteroid therapy, adherence

should be assessed, including the amount (grams/tubes) and duration

(consecutive days) of use. If possible, in-patient therapy for patients with

severe AD can allow direct observation and intensive education. Potential

complicating factors should be investigated, such as disease exacerbation by super

infection, irritants, or allergens. The latter can include immediate

hypersensitivity reactions to foods and aeroallergens as well as delayed

hypersensitivity to contact allergens, including components of moisturizers and

topical mediations.

Monitoring

corticosteroid use

Topical steroids can cause side effects if abused. It is

advisable to educate patients about the quantities to apply, for example the adult fingertip unit. A strip of ointment measured

from the distal phalangeal crease to the tip of the finger, or approximately 0.5 g, being

applied over an area equal to two adult palms, following the rule of 9's that

measures the percent of affected area and use of charts that propose amounts

based on patient age and body site. It would seem prudent to monitor the

height and weight in young children if they have severe dermatitis requiring

moderately potent or potent steroids; however, any effects on growth are more

likely to arise from active dermatitis rather than the treatment. Local side

effects, such as permanent telangiectasis on the cheeks in babies and striae of

the breasts, abdomen and thighs in adolescents, may be minimized if appropriate

steroid strengths are used. Particular care is required around the eyes, as

glaucoma may be induced by topical steroids. When there are concerns about side

effects, the topical calcineurin inhibitors, pimecrolimus and tacrolimus, may

prove to be helpful.

Topical

calcineurin inhibitors

TCIs can be considered as first-line therapy along with

appropriate use of moisturizing agents. Two topical

calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) have been approved by the US Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) for the treatment of AD: tacrolimus 0.03% and 0.1%

ointment (for “moderate to severe” disease) and pimecrolimus 1% cream (for

“mild to moderate” disease) not

controlled by topical corticosteroids. These

agents suppress T-cell activation and modulate the secretion of cytokines and other

pro inflammatory mediators; they also decrease mast cell and dendritic cell

activity. Their efficacy in the treatment of AD has been proven in

adults and children ≥2 years of age (and, for pimecrolimus, infants ages 3–23

months, although it is not approved for this group). Both agents have been shown to be effective in

short-term (3–12 weeks) and long-term (up to 12 months) studies in adults and

children with active disease.

A

meta-analysis of 25 RCTs found tacrolimus 0.1% to be as effective as the

mid-potency TCS hydrocortisone butyrate 0.1%, whereas tacrolimus 0.03% is less

effective than hydrocortisone butyrate 0.1% but more effective than the

low-potency TCS hydrocortisone acetate 1%.

TCIs are

particularly suitable for AD affecting the face and intertriginous areas, sites

where corticosteroid-induced skin atrophy is of increased concern and TCI

therapy is especially effective. TCIs are also beneficial in patients with

frequently flaring or persistent AD that would otherwise require almost

continual use of topical corticosteroids. Recent randomized controlled studies

have shown that application of tacrolimus ointment twice weekly (weekend therapy) to “hotspots” as a proactive

management during maintenance can prevent flares of AD without

increasing the overall amount of medication used and has been shown to be effective and safe for up

to 1 year in both children and adults.

Generally,

worldwide they are perceived as second line agents, and their attraction is the

absence of the cutaneous side effects of skin atrophy, striae, telangiectasia

and bruising that may be seen with prolonged or inappropriate corticosteroid

use.

TCIs are very safe, the most common side effect

being skin burning on initial

application. This sensation often settles with

continued use in 80% of patients after 1 week

or if TCI use is preceded by a short topical corticosteroid course and so it may be worth introducing to a limited area

initially to gain patient confidence. TCIs do not

increase the risk of bacterial infections, but the risk of viral infections

such as herpes simplex virus is slightly elevated. There was a boxed warning

based on a theoretical risk of malignancy against TCI since 2006. However,

there is no convincing evidence, either from controlled studies with follow-up

of patients or from studies of patient databases that TCIs can induce malignant

disease. The largest and longest trial looking at infants treated with

pimecrolimus found no evidence of increased malignancy risk.

They

would seem to be of value for resistant eczema, particularly around the eyes

and in areas at high risk of skin thinning and also for maintenance therapy.

Oral

corticosteroids

Of note,

no systemic medications besides corticosteroids have been FDA-approved for

treatment of AD. However, in general, treatment of AD with systemic

corticosteroids should be avoided due to a propensity for significant

rebound flares upon their discontinuation and the unacceptable side effects of

long-term use. In the occasional exception of a severe, generalized acute flare

(e.g. with a specific trigger) resistant to aggressive topical management,

treatment with a systemic corticosteroid should be limited to a short course

(up to 1 week) with transition to a topical regimen,

phototherapy and/or an alternative systemic agent. Long-term use of oral

corticosteroids in AE patients is not recommended.

Oral prednisolone (typically 0.5

mg/kg) is used in the management of severe exacerbations of AE. Generally, oral

corticosteroids are well tolerated and act rapidly, which can be highly valued

by patients suffering from severe flares. Unfortunately, because there is usually

disease recurrence following cessation of treatment, the clinical benefit

achieved by oral corticosteroids in those patients who do not apply concomitant

intense topical therapy may lead to patient preference for intermittent courses

of oral corticosteroids and disengagement with topical treatment.

Second Line of Therapy

Ciclosporin

Cyclosporine (CsA) is an oral calcineurin

inhibitor that suppresses the activation of the T-cell transcription factor,

nuclear factor of activated T cells, inhibiting the transcription of a number

of cytokines, including IL-2.

Oral ciclosporin is the first

choice among systemic immunomodulators in both adults and children older than 2 years of age who are unresponsive to

conventional topical treatment or showing severe course of disease. However, the use of oral cyclosporine to treat AD is

limited by potential side effects such as nephrotoxicity (which can develop

after as little as 3–6 months of therapy) and increased blood pressure, which

seem to be dose-dependent. The duration of cyclosporine therapy is

guided by clinical efficacy and tolerance of the drug. Both short-term and

long-term therapies may be useful in AE. The drug should be administered twice a day at a

daily dose of 3–5 mg/kg/day. Low starting doses (3 mg/kg/day) and high starting

doses (5 mg/kg/day) are found to be equally effective after 2 weeks. Once

clinical efficacy is reached, a gradual dose

reduction of 0.5– 1.0 mg/kg/day every 2 weeks is recommended, until a minimal effective maintenance dose (usually

~2 mg/kg/day).

Virtually all patients respond rapidly with a reduction in eczema severity by

approximately 55% at 6–8 weeks. However, symptoms recur rapidly when drug

therapy is discontinued. Both continuous long-term

(up to 1 year) and intermittent short-term dosing schedules (3- to 6-month

courses) are efficacious. Longer term use of

ciclosporin is associated with an increased side effect profile. However, if

the dose can be reduced down to or below 2.5 mg/kg and regular monitoring of

renal function and blood pressure are satisfactory, ciclosporin may be

continued for up to 1 year.

Of note,

cyclosporine is often not sufficient as monotherapy, requiring combination with

topical corticosteroids to reach an almost complete remission.

Since an intermittent-dosage regimen (e.g.

‘weekend therapy’) will lead to lower cumulative doses of cyclosporine and is

effective in some AE patients, an individualized dosage regimen is recommended

for children and adolescence patients.

Although there are no

controlled studies available regarding the efficacy of vaccination during

cyclosporine therapy, there is no evidence for a failure during cyclosporine

either. Hence, a cessation of therapy of 2 weeks before and 4–6 weeks after

vaccination may be advisable. Clinically, there is no evidence for this

recommendation.

Third Line of Therapy

Phototherapy

Phototherapy can be one

of useful treatment modalities for moderate to severe AD. Currently, narrow‐band phototherapy seems to be the preferred option for

chronic disease for both adults and children. On average, disease activity is

reduced by approximately 30–50% at the end of a typical 24‐treatment

course. Moreover, improvement may be maintained for several months. It can be used as monotherapy or in combination with

emollients and topical steroids. Acute flares of AE should be treated with

intense treatment prior to narrow‐band UVB phototherapy and secondary infection should also be

treated. In general, phototherapy courses should be limited to one per annum.

In young children, phototherapy may be difficult for practical reasons, e.g.

lack of cooperation.

Azathioprine

Azathioprine should be considered as a

second-line choice among systemic immunomodulators in adult patients

unresponsive to or experiencing side effects with cyclosporine.

Azathioprine has a slow onset of

action than

ciclosporin, with clinical improvement after

1–2 months and full benefit requiring 2–3 months of treatment. Clinical improvement may be

maintained for several months after discontinuation of azathioprine therapy.

The

dosage of azathioprine should be adjusted according to patient's ability to

metabolize the drug as determined by the activity of the enzyme thiopurine methyltransferase

(TPMT) measured in red blood cells as individuals with

genetically determined low activity of the enzyme thiopurine methyltransferase

(TPMT) have increased susceptibility to azathioprine-induced myelotoxicity. Patients with absent TPMT activity should not receive

azathioprine; those with normal or high TPMT activity should receive azathioprine

at a dose of 1–3 mg/kg/day, and those with low TPMT activity should receive

azathioprine at a dose of 0.5–1 mg/kg/day. Measurement of red blood cell

thioguanine nucleotide (the active metabolites of azathioprine) levels is now

available as a routine assay and may be useful for titrating azathioprine dose,

particularly in patients with low TPMT levels. Regular blood monitoring is

still required for patients receiving azathioprine as TMPT polymorphisms

account for only 65% of azathioprine‐induced neutropenias. It is also important to bear in mind

the potential for drug interactions with common prescribed drugs such as

allopurinol.

Nausea, vomiting and

other gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are common while on AZA. The other side

effects include headache, hypersensitivity reactions, elevated liver enzymes

and leukopenia.

Methotrexate

MTX seems to be a well-tolerated and effective third-line

option for the long-term treatment of moderate-to-severe AD in both children

(above 8 years) and adults.

Methotrexate can be considered as a second-line

choice among systemic immunomodulators after cyclosporine.

Methotrexate has anti-inflammatory effects and reduces

allergen-specific T-cell activity. It can have efficacy for refractory AD in

adults and children with weekly administration of 7.5–25 mg or 0.3–0.5 mg/kg,

respectively, together with folic acid supplementation. This regimen is well tolerated,

with maximum clinical effect typically seen after 2–3 months of therapy. Methotrexate appears equi‐efficacious as azathioprine. Also,

and similar to azathioprine, methotrexate may result in persistent improvement

for several months after discontinuation. Clinical experience suggests that it

may be better tolerated than azathioprine. As MTX is

teratogenic, men and women of childbearing potential must use effective

contraception during therapy.

Myclophenolate

mofetil

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) inhibits the de novo pathway of purine synthesis, resulting in

suppression of lymphocyte function. It may be of benefit for recalcitrant AD in

adults and children who have

failed to respond to or are intolerant of azathioprine and/or methotrexate.

Dosing generally ranges from 1 to 3 g/day in adults and 30–50 mg/kg/day in

children, with 2–3 months of treatment typically required for

maximum effect.

MMF is generally well tolerated, with GI

symptoms being the most commonly encountered. Hematologic (anaemia, leukopenia,

thrombocytopenia) and genitourinary (urgency, frequency, dysuria) symptoms are

rarely reported.

As

MMF and EC-MPS are both teratogenic, men and women of childbearing potential

must use effective contraception during therapy.

In

summary, the approach for systemic therapy for moderate to severe AE includes

the use of short duration of therapy of ciclosporin to gain control of acute

flares.

For patients with resistant moderate

to severe AE with chronic and more stable disease both azathioprine and

methotrexate may be considered as first line options. For patients with chronic

resistant disease unresponsive or intolerant of azathioprine and methotrexate,

myclophenolate mofetil is used.

Fourth Line of

Therapy: Biologics and Emerging Therapies

Crisaborole

Crisaborole ointment 2% is a topical

phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor approved by FDA for the treatment

of mild to moderate AD in patient ≥2 years of age. PDE-4 degrades cAMP, which leads to increased

production of pro inflammatory cytokines

including IL-10 and IL-4, thereby reduces disease severity and pruritus severity.

The most common side effect is stinging or burning in the area of application.

Dupilumab

Dupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody

directed against the IL-4a receptor a-subunit, which blocks the signaling of

both IL-4 and IL-13, the two key drivers of Th 2 immune response. In 2017,

dupilumab was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for

treatment of moderate to severe AD in patients 18 years of age and older

that is not adequately controlled with topical therapy and other systemic

treatment is not advisable. A

systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of dupilumab

treatment in moderate to severe AD provided evidence that dupilumab had an

acceptable safety profile and resulted in clinically relevant improvements in

signs and symptoms of AD.

Dupilumab is administered via

subcutaneous injection of 600 mg initially and then 300 mg every other week. Dupilumab

should be combined with daily emollients and may be combined with topical

anti-inflammatory drugs as needed. It has a

favourable side effect profile, with injection site reactions and

conjunctivitis each occurring in ~10% of patients.

Apremilast

Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase-4

inhibitor, was FDA-approved in September 2014 for the treatment of

moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. However, its upstream anti-inflammatory effect,

ease of use as an oral agent, and mild side effect profile make it an interesting

treatment option for AD as well. Multiple open-labeled trials of apremilast in

moderate-to-severe AD produce conflicting reports on efficacy, some showing

fair and other showing limited efficacy.

In patients with recalcitrant atopic dermatitis,

biologics especially dupilumab or phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor like apremilast

can be used as off-label therapy. However, the cost effectiveness should be

seriously considered.

Maintenance therapy

The proactive use of topical anti-inflammatory

therapy to address subclinical inflammation is an effective, contemporary

clinical strategy for the management of AD. Proactive treatment with TCS and

TCI are effective to prevent AD flares.

The