Alopecia

areata

Salient

features

·

Alopecia

areata is a non-cicatricial hair loss in any hair-bearing area of the body with

a multi-factorial, autoimmune pathogenesis, and an unknown etiology

·

It

occurs in both genders equally and can affect every age group, although incidence

at in younger age groups is higher.

·

It

is the most common form of hair loss in children. Clinically, it presents with

well-demarcated round or oval bald spots on the scalp or other parts of the

body.

·

Of

patients with alopecia areata, 5% develop hair loss of their entire scalp hair

(alopecia areata totalis) and 1% develops alopecia areata universalis (loss of

total body hair).

·

Nail

changes include geometric pitting or sandpaper nails (trachonychia)

·

Alopecia

areata is thought to be an autoimmune disease with a possible hereditary

component.

·

In

general, alopecia areata is a medically friendly condition, but it can coexist

with other autoimmune disorders such as Hashimoto thyroiditis and vitiligo.

Introduction

Alopecia

areata is a relapsing and remitting, chronic inflammatory disease that involves

the hair follicle and sometimes the nails. It is a CD8+ T-cell –mediated, organ

specific (hair-specific) autoimmune non-cicatricial alopecia that is occurring

in genetically predisposed individualstriggered by some yet unknown environmental

factors.

AA

can undergo spontaneous remission. As the current episode duration is an

important prognostic indicator, AA is categorised as acute (<12 months) or

chronic (>12 months).

In the

acute progressive stage of alopecia areata, T lymphocytic infiltrates are seen

around, and sometimes within, the hair bulb region of anagen follicles, which has

been described as a “swarm of bees”. These cytotoxic CD8+ NKG2D+ T

cells, which produce interferon (IFN)-γ, are

thought to play a key role in pathogenesis.This inflammation leads to

increased number of catagen hairs and finally to dystrophic, miniaturized

hairs. Despite the presence of this inflammatory infiltrate, the follicle

retains its potential to produce hair, implying that the follicular stem cells

remain viable.

The chronic relapsing nature of

alopecia areata and its profound effect on physical appearance make the

development of this condition a distressing and life-changing event for many

affected individuals.

Epidemiology

The average lifetime risk of developing alopecia

areata is estimated to be 1-2%. AA may

appear at any age, but as many as 60% of patients with AA will present with

their first patch before 20 years of age, and

80% before the age of 40 years.

AA affects both sexes

with equal frequency; however men are afflicted with the severe forms of the

disease more often.

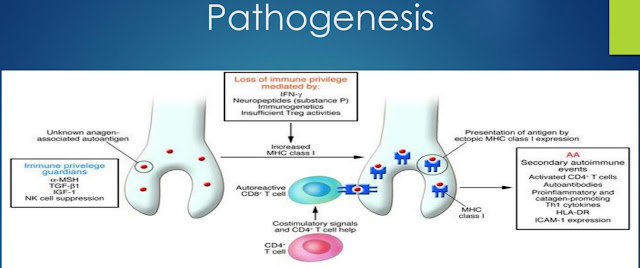

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis of alopecia areata

The

pathogenesis of AA remains incompletely understood to date, although a complex

interplay between loss of immune privilege in the hair follicle,

autoimmune-mediated hair follicle destruction and up regulation of inflammatory

pathways has been advocated to explain the development of this condition. Auto reactive

CD8 and CD4 T cells infiltrate the hair follicles and attack hair

follicle-derived auto antigens while sparing the stem cell compartment.

There

are multiple hypotheses regarding the pathogenesis of alopecia areata, ranging

from an environmental insult such as a viral infection to a genetic

susceptibility to T-cell-driven autoimmunity. The latter could result from a

primary attack of the immune system against the hair follicle or a breakdown in

the hair follicle’s immune privilege which leads to a secondary attack by the

immune system (s. Of course, it is most likely that there is interplay of

several factors and depending upon the particular patient or subtype, one

factor may play a more important role.

Evidence

in support of a T-cell-driven autoimmune process includes the observation that

CD8+ T cells are the initial intrafollicular

lymphocytes to appear in alopecia areata. Cytotoxic CD8+ NKG2D+ T cells,

which produce interferon (IFN)-γ, are thought to

play a key role in pathogenesis. Involvement of IFN-γ and

the γ-chain cytokines (IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and

IL-21) implicates downstream signaling via the JAK (Janus kinase)/STAT pathway.

These findings represented the rationale for cytokine-targeted therapy and

indeed the JAK inhibitors tofacitinib and ruxolitinib did promote

hair regrowth in clinical studies.

Under the genetic backgrounds,

some triggers, such as viral infection, trauma, physical/emotional stresses,

activate auto reactive CD8 + T cells and Th1 cells that produce IFN-gamma.

IFN-gamma up regulates CXCL10 expression and IL-15 production with its chaperone

receptor IL-15R from hair follicle keratinocytes (outer root sheath). IFN-gamma

also collapses hair follicle immune privilege that exposes auto antigens to

auto reactive CD8 + T cells. Th1 and Tc1 cells show chemotactic activity toward

CXCL10. Effector cell is NKG2D + CD8 + T cells in AA pathogenesis.

Collapse of the hair

follicle’s immune privilege may play a role in the pathogenesis of alopecia

areata which leads to a secondary attack by the immune system. Normally, anagen

hair follicles express low levels of MHC class I molecules (thereby minimizing

presentation of auto antigens), up regulate immunosuppressant molecules such as

TGF-β1 and α-MSH, and do not activate natural killer (NK) cells by

expressing UL16 binding protein 3, an NKG2D ligand. In that hair matrix immune

privilege is restricted primarily to the anagen phase, it has been postulated

that an auto antigen from melanocytes, which are active during the anagen

phase, could be responsible for initiating the immune response against the hair

follicle.

However,

if hair follicle immune privilege (HF-IP) is collapsed by stressors, auto

antigens are revealed, resulting in an autoimmune reaction by NKG2D + CD8 +

auto reactive T cells that causes the unique pathological feature called

"swarm of bees" in the acute phase of AA. Th1 cytokines, as

represented by interferon (IFN)-γ, are dominantly detected in AA lesions and

may induce the collapse of HF-IP, including the up- regulation of MHC class I.

Heredity also plays a

part. Overall, nearly 25% of patients have a positive family history. Patients

with “early onset, severe, familial clustering alopecia areata” have a

significant association with the HLA antigens DR4, DR11, and DQ7. A family history of alopecia areata is more common in those

with disease onset before the age of 30 years. The “later

onset, milder severity, better prognostic” subsets of patients have a lower

frequency of familial disease and do not share these HLA antigens.

Alopecia areata

causes a disturbance in the normal dynamics of the hair cycle. Anagen follicles

are precipitated into telogen.

Follicles are able to

re-enter anagen but, whilst the disease is active, are unable to progress

beyond the anagen 3–4 stage. It has been suggested that they then return

prematurely to telogen and that these truncated cycles continue until disease

activity wanes.

The inflammatory

infiltrate in alopecia areata is concentrated in and around the bulbar region

of anagen hair follicles. The sparing of white hair sometimes seen in alopecia

areata has also raised the possibility that alopecia areata is primarily a

disease of hair bulb melanocytes.

Proposed pathodynamic changes in alopecia areata.

An inflammatory attack on anagen follicles precipitates follicles into telogen.

Follicles re-enter anagen but development is halted in anagen 3–4 and follicles

return to telogen prematurely.

The

onset or recurrence of hair loss is sometimes triggered by:

o

Viral infection

o

Trauma

o

Hormonal change

o

Emotional/physical stressors

Clinical features

AA

can present with a wide range of clinical heterogeneity, including a very

sudden and dramatic hair loss.

Most patients have no

symptoms, and a bald patch is noted incidentally, often discovered by a

hairdresser, by a parent, or friend. Other patients describe a burning, prickly

discomfort in the affected areas—this is known as trichodynia. Alopecia areata is conventionally classified as patchy

alopecia, alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis.

Patchy alopecia areata

Patch

alopecia areata can affect any hair-bearing area, most often the scalp,

eyebrows, eyelashes and beard.

Patchy

alopecia areata has three stages.

Sudden loss of hair

Enlargement of bald patch or patches

Regrowth of hair

Alopecia areata commonly presents

as sudden onset of one (unifocal) or more (multifocal), discrete, oval

or round, non-scarring, well-circumscribed, totally bald patches with a smooth

surface that enlarge in a centrifugal pattern. Often the

patches are from 1 to 5 cm in diameter. A few resting hairs may be found within

the patches. The

skin within the bald patch appears normal or slightly reddened. The follicular

openings are preserved and there is no atrophy. In the acute stages, gentle

pulling from the periphery of bald areas will yield more than 10 hairs. AA

typically presents on the scalp in 90% of cases, most commonly involving the

occipital scalp. Approximately half will present with a solitary lesion.

Characteristic hallmarks of alopecia areata are “black dots” (cadaver hairs, point noir), resulting from hair that breaks before it reaches the skin surface. Short, 3-4 mm in length, easily extractable broken hairs, known “exclamation point” hairs (i.e. distal end broader than the proximal end, with a blunt distal end and taper proximally) can often be seen, particularly at the margins of the bald patches during active phases of the disease when the broken hairs (black dots) are pushed out of the follicle. Microscopy shows a thin proximal shaft and normal caliber distal shaft. Exclamation mark hairs occur only in acute forms of alopecia areata and are not seen in patients with long-standing areas of hair loss. Another feature is the presence of Caudability hairs- a kink in the normal looking hairs, at a distance of 5-10 mm above the surface, when the hair is forced inwards or bent.

Regrowth

is often at first fine and white, they may be curly when previously straight,

but usually the hairs gradually resume their normal caliber and color within a few weeks or months.

It may

take months and sometimes years to regrow all the hair.

In

exceptional cases where re-growing hairs remain non-pigmented the possibility

of concurrent vitiligo should be considered.

Diffuse alopecia areata

Diffuse

AA is described as a unique AA in

which no patchy areas of hair loss are present and instead, demonstrates widespread scalp hair

thinning and increased serum IgE level. In diffuse

AA, hair thinning is acute and diffuse throughout the whole

scalp. This reduced hair density can be more evident on androgen-dependent

areas of the scalp. Prognosis is generally favorable,

especially as compared to other variants of alopecia areata, namely, alopecia

areata totalis, universalis and ophiasic areata.

Diffuse

AA is more common in patients

under the age of 40, especially in those from 20 to 40 years of age with a

strong female predominance.

Dermoscopic

signs are characteristic of AA and consist of broken hairs, black dots, yellow

dots, newly-grown short hairs, short vellus hairs, and exclamation mark hairs.

Histopathology of scalp biopsies of diffuse AA

showing typical features of AA which consists of increased proportion of

catagen and telogen hair follicles, and more intense infiltration comprising of mononuclear

cells, eosinophils, and T lymphocytes (CD3 + , and

CD8 + T) cells around hair bulbs in diffuse AA.

Hypersensitivity

may be involved in the pathogenesis of diffuse AA and the acute onset of hair

loss may be related to a relatively more intense local inflammatory

infiltration of hair loss region and an increase in serum IgE level.

Eyelashes AA

Hair

loss may also occur exclusively in the eyelashes. Eyelash AA affects young

female patients more than males and is seen more commonly in the upper than

lower lashes. The main differential in these patients is trichotillomania.

Alopecia totalis (AT) and

Alopecia universalis (AU)

Alopecia

totalis & alopecia universalis AT, hair loss of the entire scalp, and AU,

hair loss of the entire scalp and body are more severe forms of AA. An

estimated 7% of patients with AA can develop AT or AU during their clinical

course. When considering AT and AU, it is helpful to distinguish the age at

initial onset, as clinical characteristics vary based on this. Patients with an

early onset of AT or AU are more likely to have a family history of AA, nail

dystrophy or a history of concomitant medical disorders than those with late

onset.

Reticular variant

Reticular type has a

net-like pattern with multiple active and regressing patches, in which the

patient experiences hair loss in one area while at the same time undergoing

spontaneous regrowth in other sites.

Ophiasis

Ophiasis

is continuous band-like hair loss in parietal, temporal, occipital regions. It

is associated with poor prognosis.

Sisapho

The very rare ophiasis inversus, also called sisaipho type, is just the

clinical opposite of ophiasis, presents with hair

loss in the central scalp, resembling androgenetic alopecia.

Canities subita

An

intriguing feature of alopecia areata is the sparing of white hairs. In

patients with grey hair, which is an admixture of pigmented and non-pigmented

hair, the disease process appears preferentially to affect pigmented hair, so

that non-pigmented or white hair is spared by the inflammation and remain on

the scalp while dark hair falls out very quickly and is probably the

explanation for people ‘going white overnight’ in diffuse alopecia areata. The sudden

loss of pigmented hair is considered an acute episode of AA.

Alopecia areata of the nails

The

nails are an important component of the clinical picture when considering a

diagnosis of AA. Nail involvement can frequently be seen in patients with AA,

with a reported incidence ranging from 7 to 66%. Nail changes can involve one

nail, several nails or all 20 nails. Nail changes are reportedly more common in

severe patterns of AA, especially in

long-standing cases with extensive involvement.

The

most common change is geometric pitting, characterized by diffuse, uniform,

fine superficial pitting of the nail plate, i.e.

pitting in organized transverse or longitudinal rows

giving the nail a "hammered brass" appearance, which is seen in

approximately 28-34% of patients with AA. Punctate leukonychia is also common and

the distribution of white spots is usually geometrical as in pitting.

Trachyonychia (sandpaper-like roughness) or rough nails, is characterized by

brittle, thin nails with excessive longitudinal ridging and has been shown in

an estimated 3-12% of patients with AA. Onychomadesis, or complete nail

shedding from the proximal portion of the nail, can be associated with acute AA.

Of note, nail changes are not as significant in the more diffuse variant AA

incognito.

|

ALOPECIA AREATA: DISEASE AND

GENETIC ASSOCIATIONS |

|

Associated diseases |

|

·

Atopy (allergic rhinitis, atopic

dermatitis, asthma); >40% in some studies ·

Autoimmune thyroid disease (e.g. Hashimoto

thyroiditis), vitiligo, inflammatory bowel disease ·

Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome type

1 (autosomal recessive; due to mutations in the autoimmune regulator gene [AIRE]; up to 30% of patients have alopecia areata) ·

Type 1 diabetes increased in relatives of patients with alopecia areata |

|

HLA associations |

|

·

HLA-DQB1*0301 (DQ7), HLA-DQB1*03 (DQ3), and

HLA-DRB1*1104 (DR11); HLA-DQB1*03 appears to be a susceptibility HLA marker

for all forms of alopecia areata, whereas the HLA alleles DRB1*0401 (DR4) and

HLA-DQB1*0301 (DQ7) are considered markers for severe longstanding alopecia totalis/universalis |

Comorbid autoimmune disorders

AA

is thought to be an immune-mediated disease of the hair follicle and frequently

occurs in association with other autoimmune diseases, including thyroid

disease, celiac disease, pernicious anemia, Addison's disease, vitiligo, lupus

erythematosus, atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis, rheumatoid arthritis and

myasthenia gravis. Approximately 38% of patients with AT or AU have comorbid

autoimmune disorders; the most common of these is atopic dermatitis.

AA

is frequently associated with thyroid autoimmunity, including Hashimoto

thyroiditis and Grave's disease, with an incidence between 8 and 28%. AA may be

the only clinical manifestation of celiac disease and it has been suggested

that screening for the antibodies found in celiac disease (antigliandin and

antiendomysial) is warranted in the work-up of patients with AA.

There

is a higher prevalence of vitiligo in patients with AA. It is postulated that

both AA and vitiligo are caused by an autoimmune response targeted to hair

follicle and melanocyte antigens, respectively. This reported association has

even been shown to co localize within the same lesion.

Regarding

atopy, it is seen more commonly in patients with AA or their first-degree

relatives than the general population, regardless of AA subtype or extent. In

fact, atopic diseases, including asthma, atopic dermatitis and hay fever, are

associated with 10-60% of AA patients. Of note, AA patients with atopy have

been reported to have a higher incidence of ophiasis pattern of hair loss and

nail involvement.

Rheumatoid

arthritis is found to be associated with AA in 0.9% of patients in one study.

AA is a non-motor symptom that can be found in patients with myasthenia gravis

with an incidence ranging from 0.3 to 3%. Of note, in patients with myasthenia

gravis with AA and thymoma, there are reports of improvement of AA following

thymectomy.

Patients

with AA typically have a history of more autoimmune diseases in their family as

well. However, having more than one atopic or autoimmune disease does not place

patients at an increased risk of AA.

Comorbid genetic abnormalities

Down

syndrome has been associated with an increased incidence of autoimmune

disorders, including AA. The incidence of AA association with Down syndrome has

been reported between 1 and 11%.

AA

affects about one-third of patients with autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type

I (APS I), an autosomal recessive disorder with organ-specific autoimmunity and

ectodermal features. APS I appear between 3 and 30 years of age and patients

often have more severe forms of AA, namely AU or AT.

Piliannulati,

which is an autosomal dominant hair disorder characterized by alternating light

and dark bands of the hair shaft, has been reported to be concomitant with AA.

However, based on current data, a direct association between piliannulati and

AA seems unlikely.

Diagnostic studies

In

many cases, the clinical characteristics of AA can lead to a swift diagnosis.

However, in some cases the clinical diagnosis may not be straightforward and

more advanced diagnostic studies may be necessary. In these cases, less

invasive diagnostic options include wash test, pull test, trichogram and scalp

dermoscopy, or more invasively a biopsy with histopathology examination may be

utilized.

Wash test

For

the wash test, patients collect hairs shed during standardized washing for quantification

and analysis. Dystrophic, anagen hairs may be present among the shed telogen

hairs in patients with presumed telogen effluvium (TE) who may in fact have AA

incognita. In AA incognito, there have been reports of greater than 100 hairs

shed daily. The modified wash test may produce from 350 to 800 terminal telogen

hairs, with dystrophic hairs comprising only a very small subset of 2-3% of

collected hairs.

Pull test

Pull test can be performed

to assess disease activity; six hairs or more shed from the periphery of the

lesion positively correlates with the disease activity. During

the pull test, gentle traction is applied to a small group of approximately

40-60 hairs to assess for hair shedding. Hairs are then examined under the

microscope. In acute AA, the pull test is very positive with extraction of

telogen and dystrophic broken roots. Dystrophic hairs are indicative of a

disease in which mitotic activity of anagen follicles has been interrupted,

such as AA and systemic chemotherapy. In active AA, hairs in the periphery of

the patch of alopecia can be easily extracted.

In

AA incognito the pull test is positive. Typically, the clinician will find

shedding telogen roots at different degrees of maturation. These are

predominantly early telogen roots, which are characterized by an epithelial

envelope surrounding the club hair. The dystrophic, broken hairs previously

mentioned in acute AA are usually absent.

Trichogram

Trichogram is a semi-invasive tool examining

the ratio of hair in various hair growth cycle phases. About 60-80 hairs are

plucked with a rubber covered haemostat after the patient has not washed their

hair for 5 days. The hair bulbs and their roots are taped to a slide for

evaluation of the hair type and anagen to telogen ratio. This study is crucial

for the diagnosis of loose anagen syndrome which has a predominance of anagen

hairs (>70%) with distorted bulbs, absent root sheaths and ruffling of the

cuticles. These findings contrast with the trichogram findings for AA, which

includes telogen and dystrophic roots.

Scalp dermoscopy

Scalp dermoscopy also known as trichoscopy

visualizes many useful patterns that are indicative of a diagnosis of AA,

including yellow dots, cadaverized hairs or 'black dots', broken hairs or

micro-exclamation mark hairs. Hair follicle ostia can be visualized easily. Of

note, loss of follicular openings indicates scarring alopecia, and excludes a

diagnosis of AA.

Overall, the most

sensitive markers for diagnosing AA are yellow dots and short vellus hairs

(shorter than 10 mm), while the most specific markers are tapered hairs with

dark thick broken tips. Black dots, micro-exclamation mark hairs and tapered

hairs correlate with AA disease activity. Black dots, yellow dots and short

vellus hairs (shorter than 10 mm) correlate with AA severity. Dermatoscopic

finding associated with a good prognosis include the transformation of vellus

into terminal hairs (increase in proximal shaft thickness and pigmentation).

Dermoscopy can also aid the clinician in finding the optimal biopsy location.

Scalp biopsy

A 4-mm punch biopsy

is standard and can be used for a more definitive diagnosis in doubtful cases.

Both horizontal and vertical sections should be evaluated.

Histopathologic

features on horizontal sections of AA depend on the stage of the lesion and

disease duration. This can be divided into early active (acute and subacute)

and longstanding (chronic) stages.

Inflammation is a

hallmark of active AA. Anagen follicles at the margins of expanding patches of

alopecia areata characteristically show a peribulbar inflammatory cell

infiltrate, composed of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, together

with macrophages, langerhans cells and cells expressing NK cell markers,resembling

a 'swarm of bees' that may invade the follicular epithelium and matrix, and

even extend into fibrous tracts. Active areas are more likely to demonstrate

dilated follicular infundibula, intrabulbar infiltrate, reduction in

anagen/telogen ratio and increased terminal catagen and telogen hairs.

Later, in the chronic

phase, increased numbers of miniaturized, vellus-like hair follicles as well as

many fibrous streamers with lymphoid cells or loss of pigment may be seen.

Inflammatory infiltrate may also involve miniaturized hairs.

Eosinophils have been

noted in the peribulbar inflammatory infiltrate and fibrous tracts in all

stages of AA. Melanin has also been noted in fibrous streamers. Pigment casts

within follicular canals and follicular mucinosis have also been described.

Fibrous streamers are birefringent negative for collagen. Therefore, polarized

light may be useful to distinguish between the fibrous streamers seen in

chronic non-scarring AA and the follicular scars in scarring alopecia.

An absence of the

classic inflammation in AA has been reported, which can cause particular

difficulty in diagnosing AA. Therefore, in the setting of a lack of lymphocytic

infiltrate, other diagnostic clues include: increased number of terminal

catagen/telogen follicles, miniaturization of follicles, pigment casts within

the hair canal and eosinophils, melanin or lymphocytes in fibrous streamers.

In contrast to the

inflammatory scarring alopecias, little or none of the inflammatory infiltrate

is seen around the isthmus of the hair follicle, the site of hair follicle stem

cells. This may explain why follicles are not destroyed in alopecia areata.

An

exclamation-mark hair: pathognomonic of alopecia areata.

Types

of Alopecia Areata and Their Clinical Presentations

Panel A

shows the most common presentation of alopecia areata, with typical round areas

of complete hair loss in normal-appearing skin; multiple alopecic patches may

coalesce.

Panel B

shows alopecia areata totalis, characterized by the complete loss of scalp

hair, and

Panel C

shows alopecia areata universalis, characterized by the complete loss of

body hair.

Panel D

shows a condition known as ophiasis, in which hair loss in the occipital scalp

skin is highly resistant to therapy.

Panel E

shows a diffuse variant of alopecia areata characterized by the loss of hair

over a large scalp area, without bald patches.

Panel F

shows the phenomenon of overnight greying, which in some cases represents

massive, diffuse alopecia areata of rapid onset. Since only the pigmented hair

follicles are attacked, pre-existing gray or white hair becomes demasked.

Characteristic

Clinical and Dermoscopic Features of Alopecia Areata

Panel A

shows the characteristic features of alopecia areata in a father and his child.

The father’s hair loss occurred in well-circumscribed patches of clinically

uninflamed, symptomless skin in the beard region. The child has alopecia areata

totalis.

Panel B

shows “exclamation-mark hair,” in which the distal segment of the hair shaft is

broader than its proximal end, and

Panel C

shows “cadaver hairs” (comedo-like black dots).

Panel D

shows nail pitting, one of several nail changes that can be present in alopecia

areata, another being onychodystrophy.

Panel E

shows the regrowth of white hair shafts (poliosis) in an alopecic lesion.

Clinical diagnosis of AA became considerably easier with the development

of scalp dermoscopy. Dermoscopy allows confirmation of the diagnosis in

doubtful cases and provides criteria to assess disease activity and severity.

With dermoscopy the clinician can evaluate the whole scalp and predict whether

the disease is spreading or is stable. This is very important for therapeutic

decisions. In addition, dermoscopy aids in the evaluation of treatment efficacy

as it permits visualization of initial regrowth that is not easily visible to

the naked eye. The role of pathology in the diagnosis of AA is greatly reduced

with the advent of dermoscopy.

Differential diagnosis

The diagnosis can almost always

be made clinically. Clinical features, such as shape and

look of the patches, presence of exclamation point hair, nail changes (pitting

or sandpaper nails) and absence of scarring lead

to the diagnosis of alopecia areata. Moreover, positive family history and/or

the presence of associated diseases may give further evidence in cases of

doubt. In the acute phase, a peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate, which has been described

as a “swarm of bees” may be found. Since

20% patients have abnormal thyroid function, it is reasonable to check this

aspect, but restoring normal function does not always cure alopecia areata.

Non-scarring AA is a non-scarring form of

hair loss and may mimic other non-scarring alopecias, including AGA, TE,

alopecia syphilitica, trichotillomania and tinea capitis.

Androgenetic alopecia and Telogen effluvium

Diffuse AA can

be misdiagnosed as other diffuse alopecia because it lacks the characteristic

patches of AA, such as telogen effluvium (TE) and androgenic alopecia (AGA)

Dermoscopy and pathological examination are of great value in diagnostic work.

All the dermoscopic and pathological features can be found in diffuse AA

patients, such as broken hairs, black dots, and exclamation mark hairs and

mononuclear cells, eosinophils, and T lymphocytes cells around hair bulbs in

diffuse AA. However, TE and AGA lack all these features and can be excluded by

pathologic findings, i.e., a terminal/vellus ratio of <4:1 without peribulbar

lymphocyte infiltration is diagnostic of AGA, whereas the ratio >7:1

suggests TE.

Alopecia syphilitica

Alopecia syphilitica,

which occurs in approximately 4% of patients with secondary syphilis, should be

considered in the appropriate clinical setting. Clinically, alopecia

syphilitica has been described as having a non-inflammatory 'moth eaten'

appearance and less commonly can present as 'essential alopecia' with diffuse

hair loss or a combination of both. Hair loss is non-inflammatory. Diagnosis

can be confirmed with syphilis serology testing and occasionally spirochetes

can be visualized in the hair follicles.

Alopecia neoplastica

Alopecia neoplastica

may be induced by tumor metastasis to the scalp and may resemble AA, even

though the scalp usually shows some signs of inflammation. Alopecia neoplastica

must be considered in patients with underlying neoplasms, especially breast

cancer in older women. Extramammary Paget's disease has also presented as

poorly circumscribed, erythematous plaque with patchy alopecia on the scalp.

Histopathologic examination of the scalp often reveals the underlying neoplasm

and aids in diagnosing alopecia neoplastica.

In children the main

sources of diagnostic difficulty are tinea capitis and trichotillomania.

Tinea capitis

Tinea capitis is a

contagious disorder typically affecting children with a mean age of

approximately 8 years. It is rarely seen in infants and should only be

considered in the setting of patchy scaling with hair loss. Tinea capitis

usually produces scalp inflammation with mild scaling and is therefore more

easily clinically distinguished from AA.

Trichotillomania

Trichotillomania is a

psychocutaneous disorder commonly seen in children who repetitively pull out

hair from the scalp, eyebrows or eyelashes. It is classified as an impulse

control disorder with features of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Children aged

9-13 years and both sexes are commonly affected. Less commonly adults can also

be affected.

The hair loss in

trichotillomania may be asymmetrical or occur in artificial shapes. The

alopecia is not complete and short broken hairs of various lengths are usually

present across the areas of hair loss, giving a bristly texture and, unlike

exclamation mark hairs, are firmly anchored in the scalp. In most cases the

true diagnosis will become evident with time; a biopsy is useful when doubt

remains.

The pull test is

typically negative, and dermoscopy reveals question mark hairs.

There have been

reports of concomitant and isolated eyebrow and eyelash hair loss, which can

easily be mistaken for AA. In trichotillomania however the lower eyelashes are

never affected, as they are difficult to pull. In addition, patients can pull

hair from their beard, chest, underarms and pubic region. Nail biting can also

be seen with this disorder and should not be confused with other nail

abnormalities commonly seen in AA.

There have been

reports of this disorder by proxy, with parents compulsively pulling their

children's hair. Trichophagy and trichobezoars are rare disorders that can be

associated with trichotillomania and should be considered. Given all this, it

is important that psychopathology of patients and their family members be

thoroughly investigated when trichotillomania is a possibility.

Complicating matters,

AA and trichotillomania can coexist, as there has been a case reported of

concomitant trichotillomania and AA. It has been suggested that the pruritus or

other subjective symptoms can predispose children to manipulate areas of hair

loss from AA.

Scarring alopecia

Occasionally, the

early stages of scarring alopecias, including lichen planopilaris (LPP), its

clinical variant frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), and DLE can also mimic AA.

Dermoscopy is very helpful as it shows loss of follicular openings in addition

to the specific features of each disorder.

Prognosis and course

The

natural course of the disease is unpredictable, but often benign. In 80% of

patients with a single bald patch, spontaneous regrowth occurs within a year, but relapses at any given time are common. Alopecia

areata does not destroy hair follicles, and the potential for regrowth of hair

is retained for many years, and is possibly life-long. In a relatively small

number of patients, hair loss progresses to involve the entire scalp (alopecia

totalis) or the entire skin surface (alopecia universalis); in these cases,

spontaneous recovery is the exception rather than the rule. Patients with the "acute diffuse and total" sub-type have a favorable prognosis, regardless of treatment.

Poor

prognostic factors include:

MANAGEMENT

Treatment

studies are difficult to perform because the disease has an unpredictable

course and may improve on its own. Numerous therapies are available for the

management of alopecia areata and several can be utilized in combination, but none

has been shown to alter the course of the disease.

All

patients should be encouraged that spontaneous resolution may occur even in

longstanding and extensive alopecia areata due to the fact that hair follicles

are not destroyed. Spontaneous remission

occurs in up to 80% of patients with limited patchy hair loss of short duration

(less than 1 year). Such patients may be managed by reassurance alone, with

advice that re-growth cannot be expected within 3 months of the development of

any individual patch. The prognosis in long-standing extensive alopecia is less

favorable. However, all treatments have a high failure rate in this group and

some patients prefer not to be treated, other than wearing a wig if

appropriate.

|

TREATMENT

OPTIONS FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF ALOPECIA AREATA |

|

·

Topical and intralesional corticosteroids (1) |

|

·

Topical irritants (e.g. anthralin, tazarotene,

azelaic acid) (2) |

|

·

Topical minoxidil (2) |

|

·

Topical immunotherapy (e.g. squaric acid dibutyl

ester, diphencyprone) (1) |

|

·

Systemic corticosteroids, pulsed dosing* (especially if

rapidly progressive) (2) |

|

·

Systemic JAK/STAT pathway inhibitors: tofacitinib

(2), ruxolitinib (3) |

|

·

Topical or oral photo chemotherapy (PUVA) (2) |

|

·

Excimer laser (3) |

|

·

Systemic corticosteroids, chronic (2) |

|

·

Systemic cyclosporine (3) * E.g.

oral prednisolone 300 mg (5 mg/kg for children) monthly for a minimum of

three doses. |

To

date, topical JAK/STAT inhibitors have had a low response rate. Key to

evidence-based support: (1) prospective controlled trial; (2) retrospective

study or large case series; (3) small case series or individual case reports.

Limited hair loss

No treatment may be required, as spontaneous regrowth is common in 2-6 months.

2. Intralesional injections of corticosteroid suspensions is first line therapy for adult patients with less than 50% scalp involvement. Injections of triamcinolone, (5–10 mg/mL) are typically given either by needle injection or jet injection. Use 1ml syringe with a 30 gauze needle, steroid suspension should be placed at the level of mid dermis to target the affected miniature hair bulbs. For lesions of the scalp, 0.1 mL of triamcinolone acetonide at concentration of 5 mg/mL is injected at 1-cm intervals. Intralesional corticosteroid application is also effective for beard and eyebrow alopecia areata at a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL. Maximum dose of triamcinolone acetonide should be limited to 3 mL for scalp, 0.5 mL for each eyebrow and 1 mL for beard. Multiple injections are usually needed and repeated at intervals of 4-6 weeks as necessary. In some patients, resistance to steroid therapy can be explained by a decreased expression of thioredoxin reductase 1, an enzyme that activates the glucocorticoid receptor in the outer root sheath. Localized nonpermanent atrophy of the subcutaneous tissue is a common complication, particularly if large volumes and higher concentrations of triamcinolone are used, but this is temporary and recovers within a few months. Permanent skin atrophy can occur if the same skin area is injected repeatedly over months and years. Injection under significant pressure or with a small bore syringe increases the likelihood of retinal artery embolization. Other side effects include hypopigmentation, depigmentation, and telangiectasias. Hair regrowth is usually observed within 4 weeks in >60% of the treated patients. If no regrowth can be seen after 4 months of treatment, other treatment options should be considered. For children, intralesional injection of corticosteroids is not a suitable option. Intralesional steroid will not prevent the development of alopecia at other sites and is not suitable for patients with rapidly progressive alopecia or alopecia totalis/universalis.

3. Glucocorticoids: High potent topical steroids can be considered the mainstay therapy of this disease. They act by reducing the inflammatory infiltrate in the hair bulb and possibly promote spontaneous resolution. They are most useful for all limited form of the disease (unifocal or multifocal alopecia areata) involving the scalp. Clobetasol propionate 0.05% or betamethasone diproprionate foam/cream/solution twice daily for at least 3 months. Evidence of efficacy has been proven for class 1 corticosteroids when applied under occlusion and for class 2 corticosteroids when used in combination with minoxidil. Topical steroids should be applied 1 cm beyond the affected areas. A recent study showed that twice daily treatment with clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream used in 2 cycles of 6 weeks on, 6 weeks off regimen for a total of 24 weeks was more effective than hydrocortisone 1% cream used in the same regime. In patients suffering from alopecia totalis/universalis clobetasol propionate 0.05% under an occlusive dressing may promote further hair growth of the scalp. It can be applied overnight on six out of seven nights for six months and may promote long term hair growth. No evidence of systemic absorption was noted under this treatment in adult patients. A well known side effect of high potency topical steroids on the scalp is folliculitis. Upon extended treatment, skin atrophy will also occur.

4.

Topical irritants tretinoin 0.05% cream nightly, dithranol

cream (0.5-1%) applied overnight and azelaic acid.

5. Topical minoxidil 5%solution may be useful in limited disease (unifocal or multifocal alopecia areata) as a second line treatment. It may also be used to prevent relapse. It should be applied twice daily and may also be used for regions not suitable for topical steroid (beard and eyebrows). Better results can be achieved when minoxidil is used in combination with class II topical corticosteroids. Minoxidil shows little efficacy in alopecia totalis and universalis. Contact dermatitis and hypertrichosis are the most common side effects. Minoxidil foam, which does not contain propylene glycol, has less irritating effects than the solution.

6.

Onion juice: applied twice daily for 2 months. Mild

erythema may appear. Probably the worst smelling treatment.

Extensive hair loss

A reliable, standard therapy is not available.

2. Application of minoxidil 5%

solution or foam q.d. or b.i.d. may be attempted, but efficacy has not been

ascertained.

3.

Immunomodulator: Elemantal zinc 50mg bd for 3-6 months.

4.

Systemic glucocorticoids:

Several investigators have reported the use of pulsed oral and

intravenous corticosteroids in rapidly progressing or widespread

disease. Approximately

80% of patients will respond to high-dose systemic corticosteroids (e.g. 40 mg

triamcinolone intramuscularly monthly for 6 months or a 6‐week tapering course of oral prednisolone (starting at 40

mg/day);

however ~50% will relapse with dose reduction or cessation of therapy. However, long-term treatment is frequently needed to maintain growth,

and the attendant risks should be carefully weighed against the benefits. A 5 mg

oral dexamethasone on 2 consecutive days a week shows an excellent regrowth

after 6 months of treatment. Monthly methylprednisolone is

administered at a dose of 500 mg/day for 3 days or 5 mg/kg twice a day for 3

days in children. More than 60% of patients with widespread patchy alopecia

responded. Half of the patients with alopecia totalis had a good response,

while a quarter of those with universal alopecia responded. Patients with

ophiasic alopecia areata did not respond. Systemic corticosteroid should not be

used as routine treatments because they do not alter the long-term

prognosis and can cause side effects such as striae, acne, obesity, cataracts

and hypertension.

5.

Induction of

Allergic Contact Dermatitis–Topical

immunotherapy (with diphencyprone or squaric acid dibutylester) is a

non-FDA-approved treatment for extensive disease. Contact immunotherapy

is the most effective and best-documented treatment for corticosteroid

refractory, prolonged and extensive disease (alopecia areata totalis and

universalis), but is available in only a few centers. The patient is sensitized

to a potent allergen and the same allergen is then applied to the scalp,

usually at weekly intervals, in a concentration sufficient to induce a mild

contact dermatitis. The contact allergens that have been used in the treatment

of alopecia areata include diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) and squaric acid

dibutylester (SADBE). Most centers now use DPCP. 50–60% of patients achieve a

worthwhile response. Patients with extensive hair loss are less likely to

respond. Other reported adverse prognostic features include the presence of

nail changes, early onset and a positive family history. Treatment is

discontinued after 6 months if no response was obtained. The response in

patients with alopecia totalis and universalis is less favorable. Most

patients will develop occipital and/or cervical lymphadenopathy during contact

immunotherapy. This is usually temporary but may persist throughout the

treatment period. Severe dermatitis is the most common adverse event, but the risk

can be minimized by careful titration of the concentration. Cosmetically

disabling pigmentary complications, both hyper- and hypo pigmentation

(including vitiligo), may occur if contact immunotherapy is used in patients

with racially pigmented skin.

The

mode of action of contact immunotherapy is unknown. Happle suggested that the

contact allergen competes for CD4 cells, attracting them away from the

perifollicular region (‘antigenic competition’). Other suggested mechanisms include

non-specific stimulation of a local T-suppressor-cell response and increased

expression of TGF-β in the skin, which acts to suppress the immune response. Almost all patients respond and many stay free of disease for

long intervals, although recurrence are the rule.

|

TOPICAL IMMUNOTHERAPY FOR ALOPECIA

AREATA |

|

Treatment protocol for diphencyprone (DPCP) or squaric acid dibutyl

ester (SADBE)* |

|

· Sensitize with a 2%

solution in acetone applied to a 4 × 4 cm area on one side of the scalp · After 1 week (2 weeks

if the initial reaction is severe), a 0.001% solution is applied to all

affected areas on the same side of the scalp · Each week, DPCP or

SADBE is applied to the same side of the scalp >The concentration is titrated according to the

severity of the reaction the previous week, with a goal of maintaining a

low-grade, tolerable degree of erythema, scaling, and pruritus for 24–36

hours after application >Concentrations are increased

incrementally as follows: 0.001%, 0.01%, 0.025%, 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.25%, 0.5%,

1%, 2% · Once hair growth is

established, the other side is also treated · Initial responses are

usually seen after 12 weeks, and therapy is discontinued if there is no

response by 24 weeks · Frequency of treatment

can be decreased in the presence of full regrowth |

|

Additional information |

|

· Acetone solutions

should be applied using a generous amount of cotton at the end of a wooden

stick† · Following application: >The sensitizer is

left on the scalp for 48 hours, then washed off >Patients should avoid

touching the scalp for 6 hours >The scalp should be protected from light to avoid

degradation of DPCP · SADBE must be

refrigerated · Side effects include

lymphadenopathy, severe or widespread eczematous reactions, and post

inflammatory pigment alterations (particularly in patients with darkly

pigmented skin) |

|

Contraindications |

|

· Pregnancy (although

teratogenicity has not been established) ·

Malignancies and blood dyscrasias * Both not FDA-approved. † Application by medical personnel is

recommended. |

Immunosuppressive treatment

Immunosuppressive agents namely sulfasalazine, methotrexate, and cyclosporine can be used in the treatment of alopecia areata.

Sulfasalazine therapy can be an alternative treatment option in persistent alopecia areata cases. Studies have shown favorable treatment response, but a high relapse rate. The most common side effects include nausea, vomiting, headache, fever, and rash; less commonly hematologic abnormalities and hepatotoxicity can develop.

Severe forms of alopecia areata resistant to conventional topical and/or systemic treatments may respond to methotrexate. In a retrospective study, weekly 15–25 mg methotrexate with or without 10–20 mg prednisolone daily was reported to be effective in 64% of cases.

Cyclosporine has been used alone or in conjunction with corticosteroids variable response rates. Use of cyclosporine is limited because of side effects and high relapse rate. Side effects include nephrotoxicity, immune suppression, hypertension, and hypertrichosis of body hair.

JAK inhibitors

Recent data support

the role of Janus kinase (JAK) mediated pathways in alopecia areata. Interferon

gamma, interleukin-2 and IL-15 play a significant role in maintaining the auto

reactive CD8+T cell infiltrate in AA. Their receptors signal through JAK1, JAK2

and JAK3. The inhibition of these cytokine receptors with JAK inhibitors can

lead to a reversal of AA.

Tofacitinib

citrate is a small-molecule selective Janus kinase 1/3 (JAK 1/3) inhibitor that

was approved by FDA, in late 2012, for the treatment of moderate-to-severe

rheumatoid arthritis. A patient

with longstanding alopecia universalis, treated with tofacitinib for psoriasis

had hair regrowth, being the first documented case of alopecia areata

responding to tofacitinib. After eight months of tofacitinib treatment

(5 mg twice daily for 2 months followed by 10 mg in the morning and

5 mg at night thereafter), the patient had full regrowth of hair at all

body

sites. There have been other case

reports showing efficacy of tofacitinib treatment. Adverse effects of

tofacitinib use include increased risk of severe infections including

tuberculosis, anemia, neutropenia, headache, and mild nausea.

Another

JAK inhibitor, ruxolitinib applied topically twice daily for 12 weeks in a

patient with refractory alopecia universalis induced almost full eyebrow

regrowth and approximately 10% regrowth of scalp hair.

Several case reports

show that JAK inhibitors are promising class of drugs for AA even in cases of

severe or widespread disease. Oral baricitinib and tofacitinib citrate have also

shown a good treatment outcome with full regrowth of scalp hair in widespread

AA.

Summary

Alopecia areata is

difficult to treat. The tendency to spontaneous remission and the lack of

adverse effects on general health are important considerations in management,

and counselling, with no treatment, is the best option in many cases. Topical

and intralesional corticosteroids can be helpful in disease of limited extent.

Topical minoxidil is widely used but there is little convincing evidence of

efficacy. Contact immunotherapy is the most effective treatment for extensive

alopecia areata, although it is not widely available, and the response rate in

alopecia totalis and universalis is low. The place of systemic corticosteroids

is controversial.

Alopecia areata may

cause considerable psychological and social disability. If the prognosis is

poor (e.g. in a prepubertal atopic child with total alopecia), a full

explanation and help in adjusting to the problems of hair loss will be of far

greater value than the raising of unwarranted hopes.

What else should be

considered for alopecia areata?

Counselling

Some

people with alopecia areata seek and benefit from professional counselling to

come to terms with the disorder and regain self-confidence.

Camouflaging hair loss

Scalp

A

hairpiece is often the best solution to disguise the presence of hair loss.

These cover the whole scalp or only a portion of the scalp, using human or

synthetic fibres tied or woven to a fabric base.

A full wig is a cap that fits over the whole head.

A partial wig must be clipped or glued to existing hair.

A hair integration system is a custom-made hair net that

provides artificial hair where required, normal hair being pulled through the

net.

Hair

additions are fibres glued to existing hair and removed after 8 weeks

Styling

products include gels, mousses and sprays to keep hair in place and add volume.

They are reapplied after washing or styling the hair.

Eyelashes

Artificial

eyelashes come as singlets, demilashes and complete sets. They can be trimmed

if necessary. The lashes can irritate the eye and eyelids. They are stuck on

with methacrylate glue, which can also irritate and sometimes causes contact

allergic dermatitis.

Eyeliner

tattooing is permanent and should be undertaken by a professional cosmetic

tattooist. The colour eventually fades and may move slightly from the original

site. It is extremely difficult to remove the pigment, should the result turn

out to be unsatisfactory.

Eyebrows

Artificial

eyebrows are manufactured from synthetic or natural human hair on a net that is

glued in place.

Eyebrow

pencil can be obtained in a variety of colours made from inorganic pigments.

Tattooing

can also be undertaken to disguise the loss of eyebrows, but tends to look

rather unnatural because of the shine of hairless skin.