Seborrheic dermatitis

Salient

features

- Seborrheic dermatitis is a common inflammatory skin disease affecting various age groups.

- Infantile and adult forms

- Erythematous, greasy, scaling patches and plaques appear on scalp, face, ears, chest, and intertriginous areas.

- Severe forms, like generalized erythroderma, rarely occur.

- Etiology is unclear but may be related to abnormal immune mechanism, active sebaceous glands, abnormal sebum composition, Malassezia (Pityrosporum) spp. and individual susceptibility.

- Can be a cutaneous sign of HIV infection

- Treatment is based on symptomatic control.

Introduction

Seborrheic dermatitis is a

common mild chronic eczema typically confined to skin regions with high sebum

production and the large body folds. Although its pathogenesis is not fully

elucidated, there is a link to sebum overproduction (seborrhea) and the

commensal yeast Malassezia.

Epidemiology

The

incidence of SD 2 to 5% of the general population and

notably peaks in three age groups, in infancy between 2 weeks and

12 months of age, during adolescence, and between age 30 and 60 years

during adulthood. This observation, together with the fact that SD occurs

only in seborrhoeic areas, already raise the question whether these incidence

peaks correlate with defined environmental, microbial and/or hormonal (eg

androgen) changes in the skin milieu.

Men are afflicted more often than women in all ages. Extensive

and therapy-resistant seborrheic dermatitis is an important cutaneous sign of

HIV infection.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Etiologic links with active sebaceous glands, abnormal sebum

composition, and Malassezia furfur (Pityrosporum ovale). The cause of seborrhoeic dermatitis is

not completely understood. It is associated with proliferation of various

species of the skin commensal malassezia, in its yeast

(non-pathogenic) form. The inflammation seen in seborrheic

dermatitis may be irritant, caused by toxic metabolites (such as the

fatty acids oleic acid, malssezin, and indole-3-carbaldehyde), lipase, and reactive oxygen species..

WORKING HYPOTHESIS

In contrast to the

conventional Malassezia‐centric view of SD

etiology, the working hypothesis is that intrinsic factors of the host—such as defective epidermal barrier (①) and/or changes in the amount or

composition of sebum (②)—may

be the root cause of seborrhoeic dermatitis (SD). These

changes can be brought about, for example by genetic predisposition, host

immune function, neuroendocrine factors, nutrition, medication and

environmental factors. Once these changes have occurred, they may provide favorable

conditions for the commensal Malassezia to over colonize the area and become the dominant

species, alter skin microbiota (③), and for yeast metabolites such

as oleic acid to penetrate the defective barrier and elicit a rather non‐specific inflammatory response (④). Defects in host immune response to or clearing of

microbes may bypass the initial epidermal or sebaceous abnormalities.

Recruitment of more immune cells to the site of disruption and release of pro inflammatory

cytokines and chemokines could further disrupt epidermal differentiation and

barrier function, cause further imbalance of the

skin microbiota, and to allow more yeast metabolites and yeast to penetrate the

epidermal layers, thus trigger sustained inflammation in a vicious circle.

The role of γδ T cells is currently unknown in human SD. Restoration of barrier

function (①), modulating

sebaceous activity (②),

and modulating host immune activity (④) in combination with antifungal treatment (③) may provide more effective

intervention to break the vicious cycle of SD

Environmental factors

SD is

more common and severe in cold and dry climates in winter and improves with sun

exposure.

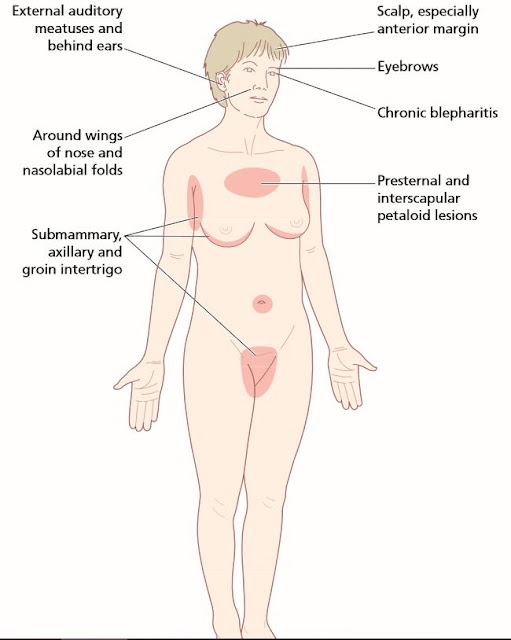

Seborrheic dermatitis: Parts of

the body typically affected

Clinical Features

Seborrheic dermatitis is defined by clinical

parameters, including:

· Red sharply demarcated patches or thin plaques covered with bran-like

flaky greasy adherent scales.

·

A predilection for areas

rich in active sebaceous glands – scalp, facial creases, ears, presternal region and large body folds (inguinal, inframammary, and

axillary). Less commonly involved sites include interscapular, umbilical,

perineum, and the anogenital crease.

·

A mild course with

little or moderate discomfort.

Seborrheic dermatitis is

most often limited in extent, but generalized and even erythrodermic forms can

occur, albeit rarely.

Clinical patterns of

seborrhoeic dermatitis

Adult

Scalp

Dandruff

Inflammatory—may extend onto non-hairy

areas (e.g. post auricular)

Face (may include blepharitis

and conjunctivitis)

Trunk

Petaloid

Pityriasiform

Flexural

Eczematous plaques

Follicular

Generalized (may be erythroderma)

Infantile

Scalp (cradle cap)

Trunk (including flexures

and napkin area)

Adult seborrheic dermatitis

In adults, seborrheic dermatitis

is generally found on the scalp and, usually of milder intensity, on the face;

less often, lesions occur on the central upper chest and the intertriginous

areas. Erythrodermic seborrheic dermatitis has been described as a rarity.

There are several morphological

variants of seborrhoeic dermatitis in the adult form.

Scalp

Dandruff (Pityriasis simplex capillitii) is a common condition and is usually the mildest form and the earliest manifestation of seborrhoeic dermatitis. Most individuals periodically experience a diffuse, slight to moderate, fine dry white scaling of the scalp and terminal hair-bearing areas of the face (beard area), but without significant erythema or irritation. Scales accumulate visibly on dark clothing; this is dandruff. This common condition may be considered the mildest form of seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp. They tend to attribute this condition to a dry scalp and consequently avoid hair washing. Avoidance of washing allows more scales to accumulate and inflammation may occur. As a result yellow bran-like flaky greasy adherent scales may occur on an inflamed base. Patients with minor amounts of dandruff should be encouraged to wash every day or every other day with antidandruff shampoos.

In

seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp, there is inflammation and pruritus in

addition to dandruff. The vertex and parietal regions are predominantly

affected, but in a more diffuse pattern than the discrete plaques of psoriasis.

Towards the forehead, the erythema and scaling are usually sharply demarcated

from uninvolved skin, with the border either at the hairline or slightly

transgressing beyond it

("corona seborrhoica"). Pruritus is usually moderate but may be

intense, particularly in patients with male pattern alopecia; folliculitis,

furuncles, and meibomitis are not uncommon complications, elicited by

scratching and rubbing.

In chronic cases there may be some

degree of hair loss, which is reversible when the inflammation is suppressed.

Behind the ears there may be redness

and greasy scaling, and a crusted fissure often develops in the fold and these

greasy scales and crusts may extend into the adjacent scalp. Both sides of the

pinna, the periauricular region, and the sides of the neck may be involved.

Face

Seborrheic

dermatitis of the facial skin is often strikingly symmetric, affecting the

forehead, medial portions of the eyebrows, the glabella,

eyelashes, upper eyelids, nasolabial folds and lateral aspects of the nose, usually in

association with involvement of the scalp. Lesions

are yellowish-red, with a typical bran-like scale. Hypo pigmentation may be a prominent feature in dark‐skinned

individuals.

Inflammation of the

anterior eyelid margin (anterior blepharitis) may occur in SD and presents as

redness of the lids

margin with flaky debris on the eyelashes,

typically near the base. When this loose debris falls into the eye, it results

in conjunctival irritation and red eye.

Trunk

On the trunk, several forms of seborrhoeic

dermatitis occur. Commonest is the petaloid form (so-called because the lesions

are petal-shaped). This is often seen in men on the front of the chest and in

the interscapular region. The initial lesion is a small, red follicular papule,

covered by a greasy scale. More often, extension and confluence of the

follicular papules gives rise to a figured eruption, consisting of multiple

circinate patches, with a fine branny scaling in their centers, and with

dark-red papules with larger greasy scales at their margins.

A rarer form, involving the trunk and

limbs, is the so-called

pityriasiform type. This is a

generalized erythematosquamous eruption, somewhat similar to, but more

extensive than, pityriasis rosea. In particular it involves the neck up to the

hair margin. It is not particularly pruritic, and it resolves spontaneously,

although somewhat more slowly than does pityriasis rosea. In some patients the

lesions may become psoriasiform.

Flexures

In the flexures, notably in the

axillae, the groins, the anogenital and submammary regions, and the umbilicus,

seborrhoeic dermatitis presents as an intertrigo, with diffuse, sharply

marginated glazed erythema with less scale. Crusted fissures develop in the

folds, and with sweating, secondary infection and inappropriate treatment, a

weeping dermatitis may extend far beyond them.

All show a tendency to chronicity and

recurrence. Occasionally, seborrhoeic dermatitis may become generalized,

resulting in erythroderma.

Adult seborrheic dermatitis has a chronic relapsing course.

Patients feel well and systemic signs are absent. Extensive and severe

seborrheic dermatitis, however, should raise the suspicion of underlying HIV

infection. Among patients with seborrheic dermatitis tested for HIV infection,

2% were found to be positive, frequently in a late stage of their disease. In

patients with Parkinson disease, seborrheic dermatitis is a common finding,

along with seborrhea. Its severity, however, is not correlated with that of the

Parkinson disease. The facial immobility of patients with Parkinson disease

might result in a greater accumulation of sebum on the skin, resulting in a

permissive effect on the growth of Malassezia.

Seborrheic dermatitis may be more common in patients with other causes of

immobility such as cerebrovascular accidents. Rebound flares of seborrheic

dermatitis can follow tapers of systemic corticosteroids.

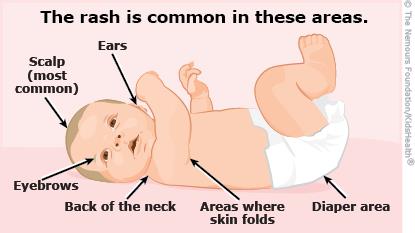

Infantile seborrheic dermatitis

Infantile

SD presents primarily with cradle cap and/or napkin dermatitis. This form usually begins about one week after birth with a

peak incidence at 3 months of age, and may persist for several

months. It corresponds to the time when neonates

produce sebum, which then regresses until puberty. Initially, mild greasy

scales adherent to the vertex and anterior fontanelle regions which may later

extend over the entire scalp. Inflammation with erythema and oozing may finally

result in a coherent scaly and crusty mass covering most of the scalp (“cradle

cap”). Lesions of the axillae, inguinal creases, neck, and retroauricular

folds are often acutely inflamed, oozing, sharply demarcated, and surrounded by

satellite lesions. Superinfection with Candida spp. or

occasionally bacteria (e.g. group A Streptococcus) can

occur. A disseminated eruption of scaly papules with a psoriasiform appearance

(“psoriasiform id reaction”) may develop on the trunk, proximal extremities,

and face in association with exuberant or superinfected seborrheic dermatitis,

especially of the diaper area.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually made on

clinical grounds without the need for diagnostic tests. HIV testing should be

considered in

any patient with severe seborrhoeic dermatitis, particularly in a patient

involved in high-risk activities.

Differential Diagnosis

Infantile seborrheic

dermatitis is distinguished from atopic dermatitis by

its earlier onset, different distribution pattern, and, most importantly, by

the absence of pruritus, irritability and sleeplessness. In contrast to atopic

dermatitis, infants with seborrheic dermatitis generally feed well and are

content.

Irritant

diaper dermatitis is confined to the diaper area and tends to spare the skin

folds.

Candidiasis of

the diaper area can result from colonization with fecal yeast and some infants

have seborrheic dermatitis with a superimposed candidal infection.

Infantile

psoriasis may be difficult to distinguish from psoriasiform seborrheic

dermatitis. Although psoriasiform diaper dermatitis can represent the initial

manifestation of psoriasis, many affected infants do not subsequently develop

psoriasis elsewhere.

When scalp

scaling is present in prepubertal children, the possibility of tinea capitis due to Trichophyton tonsurans should be considered.

Pityriasis

amiantacea is a localized or diffuse inflammatory condition of the scalp

characterized by large plates of thick asbestos-like silvery scales firmly

adherent to both the scalp and hair tufts. This condition can occur at any age,

especially adolescents and young females. Alopecia may result and is generally

non scarring unless secondary scalp infection occurs. Concomitant bacterial

skin infection, mostly Staphylococcus, may result in scarring alopecia,

so early and appropriately treatment is necessary. Young females commonly have concomitant post

auricular scales and fissures.

The most common skin diseases associated with pityriasis amiantacea are

psoriasis (35%), and eczematous conditions like seborrheic dermatitis and

atopic dermatitis (34%). Up to a third of the affected children and adolescents eventually

develop psoriasis.

A number of entities are included in the differential diagnosis

of adult seborrheic dermatitis. Distinction of

seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp from

psoriasis can be difficult. The controversial term sebopsoriasis is

often used in patients when there appears to be an overlap of psoriasis and

seborrheic dermatitis. It tends to localize to the scalp, face, and presternal

chest as seen with seborrheic dermatitis. However, the plaques of

psoriasis tend to be thicker and palpable, brighter pink color with

silvery white scale, more circumscribed and discrete,

less pruritic, and unassociated with seborrhea. In addition, features of

psoriasis may be found elsewhere.

Dry scaling of the scalp, along with dry brittle hair (as opposed

to greasy hair), is a symptom of xerotic skin (e.g. in atopic dermatitis),

frequently mistaken for (and mistreated as) seborrheic dermatitis.

Lichen simplex of the nape of the neck

occurs in females, and can mimic seborrhoeic dermatitis. The thickened plaques

in this condition are, however, intensely irritable.

Seborrheic

dermatitis of the face may closely

resemble both early rosacea and the butterfly lesions of systemic lupus

erythematosus. Lupus erythematosus rarely affects the nasolabial folds and

often has a clearly demonstrable photo distribution. Notably, seborrheic

dermatitis and rosacea frequently coexist.

The differential diagnosis

of seborrheic dermatitis of the trunk includes

pityriasis rosea (but in this latter entity the lesions are ellipsoid in shape,

have collarette-like scaling, and there is no predilection for the central

chest). The

lesions of pityriasiform type of seborrhoeic dermatitis are more widely

distributed, and there is no herald patch.

The brown scaly lesions of pityriasis versicolor

are flatter, more extensive, and less symmetrical than the lesions of petaloid seborrhoeic

dermatitis of the trunk. Microscopy of scrapings quickly establishes the

diagnosis.

In the flexures,

microscopic examination of scrapings from the advancing margin, and examination

under Wood’s light will exclude ringworm infections, candidiasis and

erythrasma.

Clinical

course and prognosis

Generally SD in adults and

adolescence has a chronic and recurrent relapsing course. Consequently the

primary goal of treatment should be control of symptoms like pruritus,

erythema, and scales, rather than cure of the disease. Also patients should be

informed that they need to prepare for a future re-outbreak and avoid

aggravating factors of SD. However, ISD has a benign, self-limited course; ISD spontaneously

disappears by 6-12 months of age. Severe exacerbation with exfoliating

dermatitis may occur, albeit rarely, but its prognosis is usually favorable. ISD

does not progress to adulthood.

Management

Summary of NICE recommendations for the treatment of SD (The

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence)

|

Type of seborrhoeic dermatitis |

First line therapy |

Second line therapy |

Additional therapy |

|

Scalp and beard |

2% ketoconazole shampoo twice a

week for a month, then once or twice a week for symptom control |

Medicated shampoos with zinc

pyrithione, coal tar or salicylic acid |

Topical keratolytic or mineral/olive oil for the removal

of scale and crust Potent topical corticosteroid scalp application for 4

weeks if there is severe scalp itch |

|

Face and body in adults |

Ketoconazole 2% cream o.d./b.d., Use as above for at least

4 weeks, then less frequently |

Mild topical corticosteroids for

1–2 weeks |

Antifungal shampoo, e.g. 2% ketoconazole, as a body wash Hygiene measures for eyelid involvement using cotton buds

moistened with baby shampoo |

|

Severe |

Review diagnosis, consider

specialist referral, HIV testing |

|

|

|

In infants |

Removal of scalp crusts with baby

shampoo and gentle brushing. Overnight soak of petroleum jelly or warmed

vegetable oil if needed. Daily bathing with soap substitute |

Topical imidazole cream:

clotrimazole 1% cream b.d./t.d.s., econazole 1% cream b.d., miconazole 2%

cream b.d. |

Topical corticosteroids not

routinely advised but may be used for certain infants with nappy rash |

Seborrhoeic dermatitis can generally

be suppressed, there is no permanent cure. Long‐term maintenance treatment may be

required but some patients only use treatment intermittently for acute,

symptomatic flares. Topical antifungals are the mainstay of therapy due to

their safety in all ages. Ketoconazole have been the most heavily investigated

topical agent in SD. New formulations may also improve patient choice, such as

2% ketoconazole foam, which was found to be popular and effective as a long‐term treatment of SD for up to 52

weeks. However, some strains of Malassezia globosa and M.

restricta are resistant to azole antifungals and this may be

associated with treatment failure. Ciclopiroxolamine, a broad spectrum antifungal and anti-inflammatory

agent, and a newer azole such as sertaconazole are

also effective topically in treating SD of the scalp as a

shampoo and face as a

cream.

Dandruff is usually treated by the

frequent and regular use of medicated shampoos which act against Malassezia yeasts,

including zinc pyrithione, ketoconazole and various tar shampoos; 1% terbinafine

solution has also been shown to be effective.

For severe dandruff with persistent

scaling or crusting, 5% salicyclic acid ointment may be useful. If secondary bacterial

infection is present or suspected, oral erythromycin or flucloxacillin may be

used.

Acute

forms of seborrhoeic dermatitis on the face, trunk and

ears are treated with topical

corticosteroids in combination with antifungals for their additional anti‐inflammatory effects, with improved

results compared with antifungal monotherapy, which can then be changed to ketoconazole

cream for long-term control. Short courses of low potency topical

glucocorticoids (Class IV or lower) should be used to suppress the initial

inflammation. Hydrocortisone ointment (0.5%) is often effective. Ketoconazole

cream (2%) is possibly a more logical therapy, which has been shown to be

equally effective. Concerns about atrophy limit the

long‐term use of

corticosteroids, especially in delicate sites such as the eyelids. Topical calcineurin

inhibitors are emerging as an effective alternative. Topical calcineurin

inhibitors (pimecrolimus and tacrolimus) have

anti-inflammatory and antifungal (tacrolimus) properties without the long-term

side effects of topical corticosteroid use. They manifest

good effects on SD by blocking calcineurin, thus preventing both inflammatory

cytokines and signaling pathways in T lymphocyte cells. Studies of topical

pimecrolimus and tacrolimus in SD have found that improvement occurred within 2

weeks and that if SD recurred after stopping treatment it was significantly

less severe. Seborrheic dermatitis tends to relapse if a maintenance regimen is

not instituted. As M. furfur has a

slow proliferation rate, an interval of two to several weeks will pass until

relapses appear. The intervals of topical therapy should follow this rhythm. Maintenance treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors

may be useful in preventing the relapse and twice weekly 0.1% tacrolimus has

been reported to be effective for up to 10 weeks in adult facial SD. Adverse

effects includes mild burning and irritation.

Patients with

seborrheic blepharitis can be treated with warm compresses and washing with

baby shampoo followed by gentle cotton tip debridement of thick scale. Avoid

ocular glucocorticoids. Ophthalmic sodium sulfacetamide ointment can be used

for resistant seborrheic blepharitis.

Other treatments reported to be of benefit in facial SD

include 4% nicotinamide cream and metronidazole 0.75% gel, and these may be

particularly useful in patients with coexistent acne/rosacea.

Frequent washing with soap and water

is helpful, possibly because removal of lipid removes the substrate for the

yeasts.

For unresponsive cases, oral itraconazole

(100 mg daily for up to 21 days) is also effective or itraconazole 200mg for

the first 7 days of the month for several months is a regime used to get

clinical improvement.

Generalized seborrhoeic dermatitis

usually responds to the medications listed above, but in recalcitrant cases

systemic steroids may be required. A 1-week course of prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg body

weight/day usually produces a rapid response, while cautioning the patient of

side effects and informing them of potential rebound flares following

discontinuation of the medication.

Infantile seborrheic dermatitis

(ISD)

The basic

principles of treatment are the same for infants. When ISD involves the diaper

areas, the use of superabsorbent disposable diapers with frequent changes

prevent the aggravation of the symptoms. Soap and alcohol containing compounds

are not recommended in cleaning the diaper lesions.

Infantile

seborrheic dermatitis usually responds satisfactorily to bathing and

application of emollients. Ketoconazole cream (2%) is indicated in more

extensive or persistent cases. Short courses of low-potency topical

corticosteroids may be used initially to suppress inflammation. Mild shampoos

are recommended for the removal of scalp scales and crusts. Avoidance of irritation

(e.g. the use of strong keratolytic shampoos including salicylic acid and

selenium sulfide that are dangerous to neonates because of the possibility of

the percutaneous absorption; and mechanical measures to remove the scales from

the scalp) is important.