Pemphigus

Salient features

1.

Pemphigus

is a group of autoimmune blistering diseases of the skin and mucous membranes

that is characterized by:

o

histologically,

intra epidermal blisters due to the loss of cell–cell adhesion of keratinocytes

o

immunopathologically,

the finding of in vivo bound and circulating

IgG auto antibodies directed against the cell surface of keratinocytes

2.

Pemphigus

is divided into three major forms: pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and

paraneoplastic pemphigus

3.

The

functional inhibition of desmogleins, which play an important role in cell–cell

adhesion of keratinocytes, by IgG auto antibodies results in blister formation

4.

Patients

with pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus have IgG auto antibodies

against desmoglein 3 and desmoglein 1, respectively, while patients with

paraneoplastic pemphigus also have IgG auto antibodies against plakin molecules

as well as a T-cell-mediated autoimmune reaction that leads to an interface

dermatitis

5.

IgA

pemphigus is characterized by IgA, but not IgG, auto antibodies directed

against keratinocyte cell surfaces and is divided into two major subtypes:

intra epidermal neutrophilic (IEN) type and sub corneal pustular dermatosis

(SPD) type

6.

Systemic

corticosteroids are a mainstay of therapy in pemphigus vulgaris, given the

rapidity of clinical response, but because of their potential side effects at

effective doses, they are combined with steroid-sparing agents

7.

These

additional therapies include immunosuppressive medications such as

mycophenolate mofetil, high-dose IVIg (non-immunosuppressive), and rituximab;

in the future, the latter may become a first-line therapy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

Pemphigus is a group of IgG

autoantibody-mediated blistering diseases of the skin and mucous membranes that

includes three major forms: pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and

paraneoplastic pemphigus. Histologically, there is intra epidermal blister formation

due to the loss of cell–cell adhesion of keratinocytes. Immunopathologic

studies serve to identify in vivo bound

and circulating IgG auto antibodies against desmogleins found within

desmosomes. Patients with pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus have IgG auto

antibodies against desmoglein 3 and desmoglein 1, respectively, while patients

with paraneoplastic pemphigus also have IgG auto antibodies against plakin

molecules as well as a T-cell-mediated autoimmune reaction that leads to

interface dermatitis. Systemic corticosteroids are a mainstay of therapy, but

due to their toxicity at effective doses, immunosuppressive medications are

regularly used as steroid-sparing agents. More recently, high-dose IVIg, which

is non-immunosuppressive, and rituximab, a B-cell-depleting monoclonal

antibody, have been added to the therapeutic armamentarium for pemphigus.

Introduction

Pemphigus

is a group of chronic blistering skin diseases in which autoantibodies are

directed against the cell surface of keratinocytes, resulting in the loss of

cell–cell adhesion of keratinocytes through a process called acantholysis.

Pemphigus can be divided into three major forms: pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus

foliaceus, and paraneoplastic pemphigus.

Pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus are the classic

forms of pemphigus. All patients with pemphigus vulgaris have mucosal membrane

erosions, and more than half will also have cutaneous blisters and erosions.

The blisters of pemphigus vulgaris develop in the deeper portion of the

epidermis, just above the basal cell layer. Patients with pemphigus foliaceus

have only cutaneous involvement without mucosal lesions, and the splits occur

in the superficial part of the epidermis, mostly at the granular layer. Pemphigus

vegetans is a variant of pemphigus vulgaris, and pemphigus erythematosus

represent a localized variant of pemphigus foliaceus.

More recently, paraneoplastic pemphigus is recognized as a

disease distinct from the classic forms of pemphigus, as it

consists of both humoral and cellular autoimmune reactions. Patients with paraneoplastic pemphigus have a known or

occult neoplasm, usually of lymphoid tissue. Painful, severe oral and

conjunctival erosions are a prominent feature of paraneoplastic pemphigus.

IgA pemphigus is characterized by IgA, but not IgG, auto

antibodies directed against keratinocyte cell surfaces and is divided into two

major subtypes:

|

|

• |

Intra

epidermal neutrophilic (IEN) type, with pustule formation throughout the

entire epidermis |

|

|

• |

Sub corneal pustular dermatosis (SPD) type, with pustules

primarily in the upper epidermis. |

|

CLASSIFICATION OF PEMPHIGUS |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Target

antigens in pemphigus A2ML1, alpha-2-macroglobulin-like-1 protease inhibitor;

BPAG1, bullous pemphigoid antigen 1

|

TARGET ANTIGENS IN

PEMPHIGUS |

|||

|

Disease |

Autoantibodies |

Antigens |

MW (kDa) |

|

Pemphigus vulgaris |

|||

|

Mucosal-dominant type |

IgG |

Desmoglein 3 |

130 |

|

Mucocutaneous type |

IgG |

Desmoglein 3 |

130 |

|

Desmoglein 1 |

160 |

||

|

Pemphigus foliaceus |

IgG |

Desmoglein 1 |

160 |

|

Paraneoplastic pemphigus |

IgG |

Desmoglein 3 |

130 |

|

Desmoglein 1 |

160 |

||

|

Plectin* |

500 |

||

|

Epiplakin* |

500 |

||

|

Desmoplakin I* |

250 |

||

|

Desmoplakin II* |

210 |

||

|

BPAG1* |

230 |

||

|

Envoplakin* |

210 |

||

|

Periplakin* |

190 |

||

|

A2ML1 |

170 |

||

|

Drug-induced pemphigus |

IgG |

Desmoglein 3 |

130 |

|

Desmoglein 1 |

160 |

||

|

IgA pemphigus† |

|||

|

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis

type |

IgA |

Desmocollin 1 |

110/100 |

|

Intraepidermal neutrophilic

type |

IgA |

? |

? |

* Members of plakin family.

† A subset of patients has IgA

autoantibodies against Dsg1 or Dsg3.

Epidemiology

Incidence and

prevalence

The incidence of pemphigus is low. Pemphigus vulgaris

(PV) is generally the commoner form, though there is some geographical

variation in the incidence of the different subtypes; thus PV is more common in

Europe, the US and India whereas pemphigus foliaceus (PF) is more common in

Brazil and Africa.

Age

PV can occur at any age but is usually seen between the

fourth and sixth decades of life. In India, patients with PV have a relatively

low age of onset of disease (mean 40 years).

Sex

Pemphigus seems to affect men and women equally.

Ethnicity

PV has been reported in all ethnic groups, but is more

common in Indian populations. Genetic variations are likely to play a major

role.

The

intraepidermal immunobullous diseases: characteristic clinical features

The

intraepidermal immunobullous diseases: immunopathology and immunogenetics

Pathophysiology

Pathogenic

Autoantibodies in Pemphigus

The hallmark of pemphigus is the finding of IgG auto

antibodies against the cell surface of keratinocytes. The pemphigus

autoantibodies found in patients’ sera are pathogenic because they induces the

loss of cell adhesions between keratinocytes, and subsequent blister formation.

Neonates of mothers with pemphigus vulgaris may have a transient

disease caused by maternal IgG that crosses the placenta. As maternal antibody

is catabolized, the disease subsides.

Desmogleins as

Pemphigus Antigens

Immunoelectron microscopy localized pemphigus vulgaris and

pemphigus foliaceus antigens to the desmosomes, the most prominent cell–cell

adhesion junctions in stratified squamous epithelia. The basic

pathophysiology of pemphigus is as follows: autoantibodies inhibit the adhesive

function of desmogleins and lead to the loss of the cell–cell adhesion of

keratinocytes, resulting in blister formation.

Compelling

evidence has accumulated that IgG auto antibodies against Dsg1 and Dsg3 are

pathogenic and play a primary role in inducing the blister formation in

pemphigus. Essentially, all patients with pemphigus have IgG auto antibodies

against Dsg1 and/or Dsg3, depending on the subtype of pemphigus. When

anti-desmoglein IgG auto antibodies are removed from the sera of patients with

pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus or paraneoplastic pemphigus (by

immunoadsorption with recombinant desmoglein proteins), the sera are no longer

pathogenic in inducing blister formation.

Desmoglein

Compensation Theory as Explanation for Localization of Blisters

The sites of blisters in pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus

are explained logically by the desmoglein compensation theory: Dsg1 and Dsg3

compensate for each other when they are co expressed in the same cell. The principal target

antigens in pemphigus are desmogleins (Dsg) 1 and 3, which are expressed in the

skin and mucosal tissue. However, the distribution of the two proteins varies

in different epithelia, such that in skin, Dsg 1 is

expressed throughout

the epidermis, but more intensely in the

superficial layers whereas

Dsg 3 is found only in the parabasal and immediate suprabasal layers. In oral

epithelium, both Dsg1 and Dsg3 are expressed through all layers

but Dsg 1 is only present at a much lower

level than Dsg3.

While patients with pemphigus foliaceus have only anti-Dsg1

IgG auto antibodies, individuals with the mucosal-dominant type of pemphigus

vulgaris have only anti-Dsg3 IgG auto antibodies. Those with the mucocutaneous

type of pemphigus vulgaris have both anti-Dsg3 and anti-Dsg1 IgG auto

antibodies.

Logical explanation for the localization of blister formation in

classic pemphigus by desmoglein compensation theory

The colored triangles represent the distribution of

desmoglein 1 (Dsg1) and desmoglein 3 (Dsg3) in the skin (A) and mucous

membranes (B). Pemphigus foliaceus sera contain only anti-Dsg1 IgG, which

causes superficial blisters in the skin because Dsg3 functionally compensates

for the impaired Dsg1 in the lower part of the epidermis (A1), whereas those

antibodies do not cause blisters in the mucous membranes because cell–cell

adhesion is mainly mediated by Dsg3 (B1). Sera containing only anti-Dsg3 IgG

cause no or only limited blisters in the skin because Dsg1 compensate for

the loss of Dsg3 mediated adhesion (A2); however, these sera induce separation

in the mucous membranes, where the low expression of Dsg1 will not compensate

for the loss of Dsg3-mediated adhesion (B2). When sera contain both anti-Dsg1

and anti-Dsg3 IgG, the function of both Dsgs is compromised and blisters occur

in both the skin and mucous membranes (A3, B3). In neonatal skin, the situation

is similar to that shown here for mucous membranes.

When sera contain only anti-Dsg1 IgG (which interferes with

the function of Dsg1), blisters appear only in the superficial epidermis of the

skin because that is the only area in which Dsg1 is present without co

expression of Dsg3. In the unaffected deep epidermis, the presence of Dsg3

compensates for the loss of function of Dsg1. Although the anti-Dsg1 IgG binds

to mucosa, no blisters are formed, because of the co expression of Dsg3. Thus, sera

containing only anti-Dsg1 IgG cause superficial blisters in the skin without

mucosal involvement, as are seen in patients with pemphigus foliaceus.

When sera contain only anti-Dsg3 IgG, they are inefficient

in producing cutaneous blisters because co expressed Dsg1 compensates for the

impaired function of Dsg3, resulting in no, skin lesions. However, in the

mucous membranes, Dsg1 cannot compensate for the impaired Dsg3 function because

of its low expression. Therefore, a serum containing only anti-Dsg3 IgG cause

oral erosions without apparent skin involvement, as is seen in patients with

the mucosal-dominant type of pemphigus vulgaris.

When sera contain both anti-Dsg1 and anti-Dsg3 IgG, they

interfere with the function of both Dsg1 and Dsg3, resulting in extensive

blisters and erosions of the skin as well as the mucous membranes, as is seen

in patients with the mucocutaneous type of pemphigus vulgaris. It is not clear why

splits appear just above the basal layer instead of the whole epithelium

falling apart. However, it is speculated that cell–cell adhesion in the

suprabasal and parabasal layers might be weaker than in other parts of the

epithelium because there are fewer desmosomes. In addition, autoantibodies,

which penetrate from the dermis, might have better access to the lower part of

the epithelia.

In pregnant women with pemphigus, autoantibodies cross the

placenta and bind to the fetal epidermis. However, neonates develop blisters if

the mother has pemphigus vulgaris, but very rarely if she has pemphigus

foliaceus. This confusing observation is also explained by the desmoglein

compensation theory. The distribution of Dsg3 within neonatal epidermis is

unlike that in adult epidermis; it is found on the surface of keratinocytes

throughout the epidermis, which is similar to its distribution in mucous

membrane. Therefore, pemphigus foliaceus sera containing only anti-Dsg1 IgG

cannot induce blisters in neonatal skin.

In pemphigus,

the disruption of cell–cell adhesion is currently thought to be mediated via

the combined effects of direct inhibition by antibodies plus subsequent signal

transduction induced by antibody binding. The direct inhibition is mediated by

steric hindrance, i.e. the binding of auto antibodies to desmogleins spatially

interferes with the adhesive interaction of desmogleins between cells.

Humoral and Cellular Autoimmunity in Paraneoplastic

Pemphigus

Patients

with paraneoplastic pemphigus develop characteristic IgG auto antibodies

against multiple antigens, including Dsg3 and/or Dsg1, multiple members of the

plakin family (plectin, epiplakin, desmoplakins I and II, bullous pemphigoid

antigen 1, envoplakin, and periplakin), and the protease inhibitor alpha-2-macroglobulin-like-1.

Anti-desmoglein antibodies play a role in inducing the loss of cell adhesion of

keratinocytes and initiate blister formation, while the pathophysiologic

relevance of the anti-plakin auto antibodies is unclear, in that plakin molecules

are intracellular and IgG cannot penetrate cell membranes. In addition to

humoral autoimmunity, cell-mediated cytotoxicity is involved in the

pathogenesis of paraneoplastic pemphigus, in which more severe and refractory

oral erosions and stomatitis as well as more polymorphic skin eruptions are

seen, in comparison with classic forms of pemphigus. It is demonstrated that

Dsg3-specific CD4+ T cells not only help B cells produce anti-Dsg3 IgG (which

causes acantholysis), but also directly infiltrate into the epidermis and

induce an interface dermatitis. Clarification of the exact roles of autoimmune

T cells should provide valuable insights into the pathophysiology of

paraneoplastic pemphigus.

The direct and indirect immunofluorescent (IF) staining pattern

of paraneoplastic pemphigus differs from that of classic forms of pemphigus. In

perilesional skin, direct IF shows deposition of IgG and the third component of

complement (C3) on epidermal cell surfaces as well as variably along the

basement membrane zone. Unlike classic forms of pemphigus, in which

autoantibodies only bind to stratified squamous epithelia, as detected by

indirect IF, auto antibodies in paraneoplastic pemphigus also react with simple

or transitional epithelia such as urinary bladder epithelium. The latter can be

used to differentiate paraneoplastic pemphigus from classic pemphigus.

Immunologic Mechanism of Pathogenic Autoantibody Production

in Pemphigus

In contrast to the significant

progress in understanding the pathophysiologic mechanisms of blister formation

in pemphigus, it is still unclear why patients with pemphigus begin to produce

the pathogenic autoantibodies.

Pemphigus

autoantibodies are composed of IgG isotypes, which may be produced after

isotype switching, and they have a high affinity towards the antigen, which may

be a result of affinity maturation of the antibodies. In addition, pemphigus

sera recognize several distinct epitopes on desmogleins, and the presence of

autoantibodies is associated with specific HLA class II alleles, including

DRB1*0402, DRB1*1401 and DQB1*0302 in Caucasians and DRB1*14 and DQB1*0503

in Japanese. All of these features suggest that autoantibody production in

pemphigus is T cell-dependent. More recently, T cells reactive against Dsg3 are

shown to be present in peripheral blood from patients with pemphigus vulgaris

as well as healthy individuals. Certain peptides from Dsg3, predicted to fit

into the DRB1*0402 pocket, are able to stimulate T cells from the pemphigus

patients.

Acantholysis

The key pathological process in PV is separation of

keratinocytes from one another, a change known as acantholysis. Mechanisms

include steric hindrance by anti‐Dsg antibodies.

Environmental factors

A number of reports have suggested that smoking may have

a protective or beneficial role in pemphigus. Human keratinocytes have both

nicotinic and muscarinic receptors for acetylcholine and these receptors may

play a role in regulating keratinocyte cell–cell adhesion.

Pesticides have also been postulated as possible triggers

in disease development and an increased risk of pemphigus has been shown in

exposed individuals. Organophosphate pesticides block the acetylcholine

breakdown pathway and so may lead to acetylcholine accumulation with resulting

loss of cell–cell adhesion in the epidermis.

A link between diet and disease development in pemphigus

has been suggested but difficult to prove. Although garlic has been proposed as

a trigger for disease development – and has been shown to induce acantholysis

in vitro – this area remains controversial.

Drug‐induced pemphigus

Drug‐induced pemphigus is rare. Approximately 80% of cases are due to drugs that contain a

thiol group, such as penicillamine, ACE inhibitors (e.g. captopril), gold

sodium thiomalate, and pyritinol. Non-thiol drugs include antibiotics

(especially β-lactams), nifedipine,

phenobarbital, piroxicam, propranolol, and pyrazolone derivatives. Up to 10% of cases of pemphigus may be

drug-induced. Lesions characteristic of pemphigus foliaceus or pemphigus

vulgaris appear several weeks or months after the responsible drug is begun.

Penicillamine is the most common culprit in drug‐induced

pemphigus and the disease may occur in 3–10% of patients on the drug, typically

after around 1 year of exposure. Penicillamine‐induced

pemphigus tends to occur in individuals with other autoimmune disorders such as

rheumatoid arthritis suggesting that immune dysregulation may be an underlying

factor. Genetic factors may also play a role as an increase in frequency of HLA‐B15

has been reported in penicillamine‐induced pemphigus. In

some patients, simple withdrawal of the drug is sufficient to induce remission

though in others treatment with corticosteroids and immunosuppressive

medication may be required.

Clinical features

Pemphigus vulgaris

Essentially

all PV patients usually start with

painful erosions in the oral mucosa and remain

localized for months, or

may be the only manifestation of the disease, or extend to involve the skin

(average lag period of 4 months), after

which generalized bullae may occur. Less frequently there may be a generalized,

acute eruption of bullae from the beginning.

Pemphigus vulgaris is therefore divided into two subgroups: (1) the mucosal-dominant

type with mucosal erosions but minimal skin involvement; and (2) the mucocutaneous

type with extensive skin blisters and erosions in addition to mucosal

involvement.

Mucous membrane lesions usually present as painful erosions.

Intact blisters are rare, probably because they are fragile and break easily.

Although erosions may be seen anywhere in the oral cavity, the most common

sites are the buccal and palatal mucosa. The erosions are of different sizes

with an irregular ill-defined border and are slow to heal, which, when extensive or painful, may result in decreased oral intake of

food or liquids. The erosions extend peripherally with shedding of the

epithelium. The diagnosis of pemphigus

vulgaris tends to be delayed in patients presenting with only oral involvement,

as compared to patients with skin lesions.

The lesions may extend out onto the

vermilion lip and lead to thick, fissured hemorrhagic crusts. Involvement of

the throat produces hoarseness and difficulty in swallowing. The esophagus also

may be involved with sloughing of its entire lining in the form of a cast. Other mucosal

surfaces may be involved, including the conjunctiva, nasal mucosa, larynx, urethra, penis,

anus, vulva

and vagina. Cytology of vaginal cells may be misread

as a malignancy when vaginal lesions are present.

Most patients develop cutaneous

lesions. Involvement occasionally remains localized to one site but more

commonly becomes widespread.

The

primary skin lesions of pemphigus vulgaris are flaccid, thin-walled, easily

ruptured blisters. They can appear anywhere on the skin surface and arise on

either normal-appearing skin or erythematous bases. Common sites of predilection are scalp, face, neck, upper chest, axillae, groin, umbilicus and

back. The fluid within the bullae is

initially clear but may become hemorrhagic, turbid, or even seropurulent. As

the blisters are fragile they soon rupture to form painful erosions that ooze

and bleed easily. These erosions extend at the edges as more epidermis is

lost which often attain a large size and can

become generalized. The erosions soon become partially covered with crusts that

have little or no tendency to heal. Those lesions that do heal often leave hyper

pigmented patches with no scarring. Associated pruritus is uncommon.

Because

of an absence of cohesion within the epidermis, firm sliding pressure with a finger

will separate normal‐looking

epidermis from dermis, producing erosion in

patients with active disease (Nikolsky sign). The lack of cohesion of the skin

may also be demonstrated with the “bulla-spread phenomenon” – gentle pressure

on an intact bulla forces the fluid to spread under the skin away from the site

of pressure (Asboe–Hansen sign, also referred to as the “indirect Nikolsky” or

“Nikolsky II” sign). Without appropriate treatment, pemphigus vulgaris can be

fatal because a large area of the skin loses its epidermal barrier function,

leading to the loss of body fluids or to secondary bacterial infections

Lesions in skin folds may form vegetating granulations,

and flexural PV merges with its variant pemphigus vegetans. Nail dystrophies,

acute paronychia and subungual hematomas have been observed in pemphigus.

Additionally, some patients will undergo phenotypic and immunological

conversion from PV to PF or vice versa over the course of their disease.

Pemphigus may deteriorate in pregnancy and the puerperium.

In some patients, initial presentation

is in pregnancy. Severe pemphigus in pregnancy may be associated with fetal

prematurity and death. Generally, the baby is healthy although neonatal

pemphigus may occur with mucosal or mucocutaneous lesions which are generally

short lived.

Pemphigus vegetans

Pemphigus

vegetans is a rare vegetative variant of pemphigus vulgaris,

characterized by vegetating erosions, and

it is thought to represent a granulomatous

reactive pattern of the skin to the

autoimmune insult of pemphigus vulgaris. Lesions are seen primarily

in the flexures and on the scalp or face.

Two subtypes are recognized: the severe Neumann type and the mild Hallopeau

type.

Patients have circulating antibodies against Dsg 3, as in PV. In some cases,

antibodies in patients with pemphigus vegetans react with desmocollin

molecules.

In

neumann type: vesicles and bullae rupture to form erosions and then form granulomatous vegetating plaques.

In

hallopeau type: Pustules rather than vesicles characterize early lesions, but

these soon progress to vegetative plaques.

The disease chiefly affects middle‐aged adults. Involvement

of the oral mucosa is almost invariable, often with cerebriform changes on the

tongue.

A

vegetative response may occasionally also be seen in lesions of PV that tends

to be resistant to therapy and remain localized for long period of time in one

location.

Pemphigus foliaceus

Patients

with pemphigus foliaceus develop well‐demarcated scaly, crusted

cutaneous erosions, often on an erythematous base, sometimes with small

vesicles along the borders, but they do not have

clinically apparent mucosal involvement even with widespread disease.

The onset

of disease is often subtle, with a few scattered crusted lesions that are

transient and are frequently mistaken for impetigo. They have a seborrheic distribution, i.e. they favor the

face, scalp and upper trunk (chest and upper back).

Because the vesicle is so superficial and fragile, often only the resultant

crust and scale are seen, the scales have been likened to cornflakes. The

disease may stay localized for years or it may rapidly progress, in some cases

to generalized involvement and become erythrodermic with crusted oozing red skin. The Nikolsky sign is present. In contrast to the extensive

oral lesions in pemphigus vulgaris, it is extremely rare, if ever, for patients

with pemphigus foliaceus to develop mucosal involvement. Generally, patients

with pemphigus foliaceus are not severely ill. They do complain of burning and

pain in association with the skin lesions.

Although the antibodies in PF can cross the placenta, the

neonate is not usually affected.

Pemphigus erythematosus

Pemphigus

erythematosus is simply a localized variant of pemphigus foliaceus, originally

described by Senear and Usher.

Typical erythematous scaly and crusted lesions of

pemphigus foliaceus appear on the nose and malar region of the face in

a butterfly distribution

and in other “seborrheic” areas. Sunlight may exacerbate the

disease. Originally, the term “pemphigus erythematosus”

was introduced to describe patients with immunologic features of both lupus

erythematosus and pemphigus, i.e. in vivo IgG and C3 deposition on cell

surfaces of keratinocytes as well as the basement membrane zone, in addition to

circulating antinuclear antibodies. However, only a few patients have been

reported to actually have the two diseases concurrently. The

antibodies recognize Dsgs together with Ro, La and double‐stranded

DNA antigens. Progression to systemic lupus erythematosus is rare. Pemphigus

erythematosus may be associated with myasthenia gravis or thymoma.

Herpetiform Pemphigus

Most

patients with herpetiform pemphigus have a clinical variant of pemphigus

foliaceus and the remainder may have a variant of pemphigus vulgaris. This

disorder is characterized by: (1) erythematous urticarial plaques and tense

vesicles that present in a herpetiform arrangement; (2) eosinophilic spongiosis

and sub corneal pustules with minimal or no apparent acantholysis

histologically; and (3) IgG auto antibodies directed against the cell surfaces

of keratinocytes. The target antigen is Dsg1 in most cases and Dsg3 in the

remainder. Some patients with herpetiform pemphigus will have features of

pemphigus foliaceus or vulgaris during the course of their disease, and some

patients will evolve into having pemphigus foliaceus or vulgaris. It is assumed

that the pathogenic blister-inducing activity of the IgG auto antibodies in

herpetiform pemphigus might be weaker than that seen in classic forms of

pemphigus. Although often clinically less severe than pemphigus vulgaris, the

course may be more chronic.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is associated with underlying

neoplasms, both malignant and benign. The most commonly associated neoplasms

are non-Hodgkin lymphoma (40%), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (30%), Castleman's

disease (10%), malignant and benign thymomas (6%), sarcomas (6%) and

Waldenström's macroglobulinemia (6%). Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic

lymphocytic leukemia together account for two-thirds of patients.

The most constant clinical feature of paraneoplastic

pemphigus is the presence of intractable stomatitis. Severe stomatitis is

usually the earliest presenting sign and, after treatment, it is the one that

persists and is extremely resistant to therapy. This stomatitis consists of

erosions and ulcerations that affect all surfaces of the oropharynx and

characteristically extend onto the vermilion lip. Most patients also have a

severe pseudomembranous conjunctivitis, which may progress to scarring and

obliteration of the conjunctival fornices. Esophageal, nasopharyngeal, vaginal,

labial and penile mucosal lesions may also be seen.

Cutaneous findings are quite

polymorphic and may present as erythematous macules, flaccid blisters and

erosions resembling pemphigus vulgaris, tense blisters resembling bullous

pemphigoid, erythema multiforme-like lesions, and lichenoid eruptions. The

occurrence of blisters and erythema multiforme-like lesions on the palms and

soles is often used to differentiate paraneoplastic pemphigus from pemphigus

vulgaris, in which lesions on the palms and soles are unusual. In the chronic

form of the disease, a lichenoid eruption may predominate over blistering

lesions. Some patients with paraneoplastic pemphigus develop bronchiolitis

obliterans, which can be fatal as a result of respiratory failure. Although

its pathophysiologic mechanism is still unclear, ectopic expression of

epidermal antigens in the setting of squamous metaplasia is thought to render

the lung a target organ. Of note, a chest X-ray or CT scan obtained at

the onset of bronchiolitis obliterans may be normal but pulmonary function

tests will show small airway obstruction that does not reverse with

bronchodilators.

IF changes are characteristic, with features of both

pemphigus and pemphigoid reflecting the broad spectrum of circulating

antiepithelial antibodies.

|

DISORDERS WITH HEMORRHAGIC

CRUSTS OF THE VERMILION LIPS |

|

1.

Herpes

simplex 2.

Herpes

zoster 3.

Erythema

multiforme major 4.

Stevens–Johnson

syndrome/TEN spectrum 5.

Pemphigus

vulgaris 6.

Paraneoplastic

pemphigus 7.

Contact

cheilitis |

IgA pemphigus

IgA pemphigus

represents a more recently characterized group of autoimmune intra epidermal

blistering diseases presenting with a vesiculopustular eruption, neutrophilic

infiltration of the skin, and in vivo bound and circulating IgA

autoantibodies against the cell surface of keratinocytes, but with no IgG auto

antibodies. IgA pemphigus usually occurs in middle-aged or elderly persons. Two

distinct types of IgA pemphigus have been described: the sub corneal pustular dermatosis

type and the intra epidermal neutrophilic type.

Patients with both types of IgA pemphigus present with

flaccid vesicles or pustules on either erythematous or normal skin. In both

types, the pustules tend to coalesce to form an annular or circinate pattern

with crusts in the center of the lesion with accumulation of the pustular

component in the dependent portion of the vesiculopustule seen in (SPD) type,

and a sunflower-like configuration of pustules is a characteristic sign of the

intra epidermal neutrophilic type. The most common sites of involvement are the

axilla and groin, but the trunk, face, scalp and

proximal extremities can also be involved. Mucous membrane involvement is rare,

and pruritus is often a significant symptom. Because the sub corneal pustular dermatosis

type of IgA pemphigus is clinically and histologically indistinguishable from

classic sub corneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon–Wilkinson disease),

immunologic evaluation is essential to differentiate the two diseases.

IgA

deposition on cell surfaces of epidermal keratinocytes is present in all cases,

as shown by direct immunofluorescence (DIF) microscopy, and many patients have

detectable circulating IgA autoantibodies, as shown by indirect

immunofluorescence (IIF) microscopy. In the sub corneal pustular dermatosis

type, IgA auto antibodies tend to react against upper epidermal surfaces, while

in the intra epidermal neutrophilic type, IgA auto antibodies are found

throughout the entire epidermis. The subclass of IgA autoantibodies is

exclusively IgA1. IgA auto antibodies in the sub corneal pustular dermatosis

type are shown to recognize desmocollin 1, while the autoimmune targets of the

intra epidermal neutrophilic type remain to be identified. A subset of IgA

pemphigus patients have IgA autoantibodies directed against Dsg1 or Dsg3,

making the autoimmune targets of IgA pemphigus more heterogeneous. The exact

pathogenic role of IgA auto antibodies in inducing pustular formation in IgA

pemphigus remains to be elucidated.

|

|

Drug-Induced Pemphigus

There are sporadic cases of pemphigus associated with the

use of drugs, in particular penicillamine and captopril. In patients receiving

penicillamine, pemphigus foliaceus is seen more commonly than pemphigus

vulgaris, with a ratio of approximately 4: 1. Although most patients with

drug-induced pemphigus are shown to have autoantibodies against the same

molecules involved in sporadic pemphigus, some drugs may induce acantholysis

without the production of antibodies. Both penicillamine and captopril contain sulfhydryl

groups that interact with the sulfhydryl groups in Dsg1 and Dsg3. This

interaction may modify the antigenicity of the desmogleins, which may lead to

autoantibody production, or their interaction may directly interfere with the

adhesive function of the desmogleins. Most, but not all, patients with

drug-induced pemphigus go into remission after the offending drug is

discontinued.

The

clinical, histologic, and immunofluorescent microscopy findings in drug-induced

pemphigus are similar to those in the spontaneous form of the disease, except

that direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin is positive in only 90% of

cases. Circulating anti-desmoglein auto antibodies are found in ~70% of

patients.

Spontaneous

remission after drug withdrawal is not always observed, especially in those

patients in whom the reaction is due to drugs that do not contain a thiol

moiety.

Investigations

Histopathology

It is essential to take a biopsy

from an early lesion in order to establish the correct diagnosis because

pemphigus blisters rupture easily.

If

the lesion is small enough, the entire vesicle can be removed for routine

histology. If the lesions are not small, the edge of a fresh vesicle or bulla

plus the inflammatory rim is recommended. Examination

of perilesional, rather than lesional, skin is recommended for DIF in order to

avoid negative staining due to secondary degeneration of target antigens and

immunoreactants. In patients with only mucosal lesions, the biopsy specimen

should consist of the active border of a denuded area, since intact blisters

are rarely encountered. Cytologic examination (Tzanck smear) is useful for the

rapid demonstration of acantholytic epidermal cells within the blister cavity.

However, this bedside test merely represents a preliminary diagnostic tool and

it should not supplant histologic examination. This is because acantholytic

keratinocytes are occasionally seen in various non-acantholytic vesiculobullous

or pustular diseases as a result of secondary acantholysis.

Preferred sites for obtaining biopsy specimens in autoimmune bullous

diseases

If

the lesion is small enough, the entire vesicle can be removed for routine

histology. If the lesions are not small, the edge of a fresh vesicle or bulla

plus the inflammatory rim is recommended. For direct immunofluorescence (DIF)

for various forms of pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid, perilesional skin is

preferred, whereas nearby normal skin is recommended in dermatitis

herpetiformis.

Pemphigus Vulgaris

The characteristic histologic finding in this form of

pemphigus is intra epidermal blister formation due to a loss of cell–cell

adhesion of keratinocytes (acantholysis) without keratinocyte necrosis. Whereas

acantholysis usually occurs just above the basal cell layer (supra basilar acantholysis),

intraepithelial separation may occasionally occur higher in the stratum

spinosum. A few rounded-up (acantholytic)

keratinocytes as well as clusters of epidermal cells and a few inflammatory

cells, notably eosinophils, are often seen in the blister cavity. Although the

basal cells lose lateral desmosomal contact with their neighbors, they maintain

their attachment to the basement membrane via hemidesmosomes, thus giving the

appearance of a “row of tombstones”. The border of a blister on the buccal

mucosa shows intraepithelial separation in the lower part of the mucosal

epithelia. The acantholytic process may involve hair follicles.

The dermal papillary outline is usually maintained and,

frequently, the papillae protrude into the blister cavity. The blister cavity

may contain a few inflammatory cells, notably eosinophils, and in the dermis

there is a moderate perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate with conspicuous

eosinophils. In rare instances, the earliest histologic finding consists of

eosinophilic spongiosis, in which eosinophils invade a spongiotic epidermis

with little or no evidence of acantholysis.

In pemphigus vegetans, supra basilar acantholysis is seen,

in addition to considerable papillomatosis and acanthosis. Characteristically,

there is an intense inflammatory cell infiltrate containing numerous

eosinophils, and intra epidermal micro abscesses are often seen.

Pemphigus Foliaceus

The histologic changes of pemphigus foliaceus and pemphigus

erythematosus are identical. Early blisters in pemphigus foliaceus have

acantholysis in the upper epidermis, within or adjacent to the granular layer.

As the blisters are superficial and fragile, it is often difficult to obtain an

intact lesion for histologic examination. As a result, acantholysis is

sometimes difficult to detect, but usually a few acantholytic keratinocytes can

be found attached to the roof or floor of the blister. Sometimes the blister

cavity contains numerous acute inflammatory cells, particularly neutrophils.

Eosinophilics pongiosis can be also seen in very early lesions of pemphigus

foliaceus. The dermis shows a moderate number of inflammatory cells, among

which eosinophils are often present.

|

|

Paraneoplastic

Pemphigus

The histologic findings of cutaneous lesions in

paraneoplastic pemphigus show considerable variability, reflecting the

polymorphism seen clinically. The lesions show a unique combination of pemphigus

vulgaris-like, erythema multiforme-like, and lichen planus-like histologic

features, sometimes in the same specimen. Intact cutaneous blisters demonstrate

supra basilar acantholysis and individual keratinocyte necrosis with

lymphocytes within the epidermis. In addition, basal cell liquefactive

degeneration or a band-like dense lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis

can be seen. Eosinophils are rare. Biopsy specimens of the severe ulcerative

stomatitis usually yield only nonspecific changes of inflammation, but the

perilesional oral epithelium should show supra basilar acantholysis.

IgA Pemphigus

The characteristic histologic feature in IgA pemphigus is

formation of an intra epidermal pustule or vesicle. The contents of the

pustules consist predominantly of neutrophils. Acantholysis is usually not

seen. IgA pemphigus is divided into two subtypes depending on the level of

intra epidermal pustule; in the sub corneal pustular dermatosis type, pustules

are located subcorneally in the upper epidermis, while in the intra epidermal neutrophilic

type, pustules involving the lower (supra basal) or entire epidermis are

present.

A. DIF is performed on skin biopsy specimens in order to

detect in vivo bound IgG. B. IIF is

performed utilizing patients' sera in order to detect circulating

autoantibodies that bind epithelial antigens.

Direct

immunofluorescence detects antibodies in a patient’s

skin. Here immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies are detected by staining with a

fluorescent dye attached to antihuman IgG.

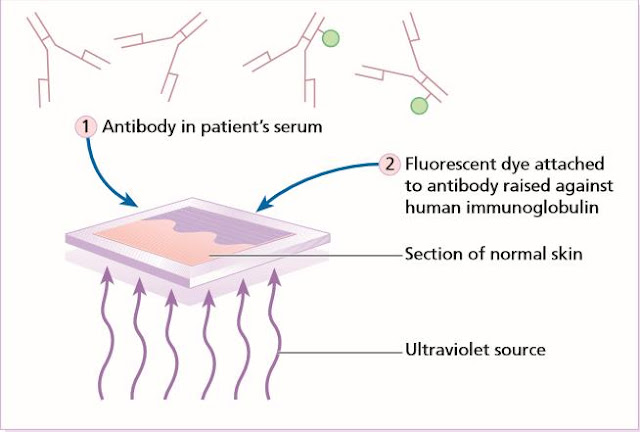

Indirect

immunofluorescence detects antibodies in a patient’s

serum. There are two steps. (1) Antibodies in this serum are made to bind to

antigens in a section of normal skin. (2) Antibody raised against human

immunoglobulin, conjugated with a fluorescent dye can then be used to stain

these bound antibodies (as in the direct immunofluorescence test).

Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) for

pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid – recommended substrates

|

INDIRECT

IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE (IIF) – RECOMMENDED SUBSTRATES |

|

|

Type of pemphigus |

Recommended substrates

(autoantibodies) |

|

Pemphigus vulgaris |

Monkey esophagus (anti-Dsg3) |

|

Pemphigus foliaceus |

Human skin or guinea pig esophagus

(anti-Dsg1) |

|

Paraneoplastic pemphigus |

Monkey and guinea pig esophagus

(anti-Dsg1, anti-Dsg3) |

|

Bullous pemphigoid |

Human skin, salt-split |

|

Mucous membrane (cicatricial)

pemphigoid |

Human skin, salt-split; normal

oral or genital mucosa or conjunctiva |

Diagnosis

For BP180, the NC16A domain is utilized and for BP230, the

N- and/or C-terminus. BP, bullous pemphigoid; EBA, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita;

MMP, mucous membrane pemphigoid; PF, pemphigus foliaceus; PNP, paraneoplastic

pemphigus; PV, pemphigus vulgaris.

Immunofluorescence (red) in bullous diseases

Disease course and

prognosis

Before

the advent of glucocorticoid therapy, PV was almost invariably fatal; most patients died within 2–5 years of the onset of the

disease because large areas of the skin lost their epidermal barrier function,

leading to the loss of body fluids or to secondary bacterial infections.

Pemphigus foliaceus had a better prognosis, except for the occasional acute

cases with generalized involvement.

The

systemic administration of glucocorticoids and the use of immunosuppressive

therapy have dramatically improved the prognosis for patients with pemphigus;

however, pemphigus is still a disease associated with a significant morbidity

and mortality. Infection is often the cause of death, and by causing the

immunosuppression necessary in the treatment of active disease, therapy is

frequently a contributing factor. With glucocorticoid and immunosuppressive

therapy, the mortality (from disease or therapy) of PV patients is

approximately 10% or less, whereas that of PF is probably even less.

Pemphigus in its

various forms typically has a chronic course with average disease duration of

10 years. Various factors have been suggested to influence this including the

site and severity of initial disease, with oral involvement an adverse

prognostic factor. Immunologically, the presence of both Dsg 1 and 3 antibodies

tends to associate with more active disease. Recent data suggest that early age

of onset and Asian ancestry associate with more prolonged disease activity. With the advent of rituximab therapy, complete remission in pemphigus may

become more common.

Management

Pemphigus Vulgaris

General

principles of management

PV

is an uncommon and potentially life-threatening disease requiring

immunosuppressive treatment. The management of active oral PV with systemic

therapies should be approached in the same way as the management of active skin

disease. The management of PV can be considered in two main phases: induction

of remission and maintenance of remission.

Remission

induction

In

remission induction the initial aim of treatment is to induce disease control,

defined as new lesions ceasing to form and established lesions beginning to

heal. Corticosteroids are the most effective and rapidly acting treatment for PV;

hence they are critical in this phase. Using corticosteroids, disease control

typically takes several weeks to achieve (median 3 weeks). During this phase

the intensity of treatment may need to be built up rapidly to suppress disease

activity. Although adjuvant drugs are often initiated during this phase, their

immediate therapeutic benefit is relatively limited because of their slower

onset. They are rarely used alone to induce remission in PV. After disease

control is achieved there follows a consolidation phase during which the drug

doses used to induce disease control are continued. The end of this

consolidation phase is defined arbitrarily as being reached when 80% of lesions

have healed, both mucosal and skin, and there have been no new lesions for at

least 2 weeks. This phase may be relatively short, but could be considerably

longer if there is extensive cutaneous erosion. Healing of oral ulceration

tends to take longer than that for skin, with the oral cavity often the last

site to clear in those with mucocutaneous PV. The end of the consolidation

phase is the point at which most clinicians would begin to taper treatment,

usually the corticosteroid dose. Premature tapering of corticosteroids, before

disease control is established and consolidated, is not recommended.

Remission

maintenance

After

induction there follows maintenance phase during which treatment is gradually

reduced, in order to minimize side-effects, to the minimum required for disease

control. The ultimate goal of treatment should be to maintain remission on

prednisolone 10 mg daily or less, with 10 mg being the dose designated

arbitrarily as ‘minimal therapy’ by international consensus. PV is a chronic

disease, and in one study 36% of patients required at least 10 years of

treatment. Systemic corticosteroids are the most important element of remission

induction and consolidation. In general, adjuvant drugs are slower in onset

than corticosteroids. Their main role is in remission maintenance. Adjuvant

drugs are combined commonly with corticosteroids with the aim of increasing

efficacy and reducing maintenance corticosteroid doses and subsequent

corticosteroid side-effects.

British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for

the management of pemphigus vulgaris 2017

An

overview of PV management

First-line therapy

Corticosteroids

•

Oral prednisolone – optimal dose not established but suggest start with

prednisolone 1 mg kg per day (or equivalent) in most cases, 0.5–1 mg kg in

milder cases

•

Increase in 50–100% increments every 5–7 days if blistering continues

•

Consider pulsed intravenous corticosteroids if > 1 mg kg oral prednisolone

required, or as initial treatment in severe disease followed by 1 mg kg per day

oral prednisolone

•

Taper dose once remission is induced and maintained, with absence of new

blisters and healing of the majority of lesions (skin and mucosal). Aim to

reduce to 10 mg daily or less

•

Assess risk of osteoporosis immediately

•

Effective in all stages of disease, including remission induction

Combine

corticosteroids with an adjuvant immunosuppressant

•

Azathioprine 2–3 mg kg per day (if TPMT normal)

•

Mycophenolate mofetil 2–3 g per day

•

Rituximab (rheumatoid arthritis protocol, 2 x 1 g infusions, 2 weeks apart)

•

More important for remission maintenance than induction, due to delayed onset

Good

skin and oral care are essential

Second-line therapy

·

Consider switching to alternate

corticosteroid-sparing agent if treatment failure with first-line adjuvant drug

(azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil or rituximab) or mycophenolic acid

720–1080 mg twice daily if gastrointestinal symptoms from mycophenolate mofetil

Third-line therapy

·

Consider choice of additional treatment

options based on assessment of individual patient need and consensus of

multidisciplinary team.

Options include

•

Cyclophosphamide

•

Immunoadsorption

•

Intravenous immunoglobulin

•

Methotrexate

•

Plasmapheresis or plasma exchange

TPMT,

thiopurine methyl transferase. Rituximab

is currently approved by National Health Service England as a third-line

treatment for pemphigus. Treatment

failure is defined by international consensus as continued disease activity or

failure to heal despite 3 weeks of prednisolone 1.5 mg kg per day, or

equivalent, or any of the following, given for 12 weeks: (i) azathioprine 2.5

mg kg per day (assuming normal TPMT), (ii) mycophenolate mofetil 1.5 g twice

daily, (iii) cyclophosphamide 2 mg kg per day, (iv) methotrexate 20 mg per

week.

PV is a serious disease, so even if the disease is

limited in extent at the onset should be treated aggressively with systemic

corticosteroids combine with immunosuppressive, because it will ultimately

generalize and the prognosis without therapy is very poor.

Because PV is caused by

pathogenic autoantibody and

there is relationship between pemphigus autoantibody and the disease activity,

therapy is aimed at both resolution of cutaneous lesions and elimination of

circulating antibody, not just to suppress local inflammation. The introduction of systemic corticosteroids and

immunosuppressive agents has greatly improved the prognosis of pemphigus;

however, the morbidity, and occasional mortality, is still significant due to

complications of therapy. Systemic corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy

for pemphigus. Immunosuppressive agents are often used for their

corticosteroid-sparing effect in order to reduce the side effects of the

corticosteroids, with the goal of therapy being to control the disease with the

lowest possible dose of corticosteroids. The titer of the circulating antiepithelial

antibody should be determined at the onset of treatment. The life-threatening

nature of pemphigus mandates aggressive therapy. The earlier

therapy is initiated, the greater the likelihood of success. Patients usually require many

months of immunosuppressive therapy, making systemic steroid monotherapy

inappropriate. Instead, early in the treatment course, begin a steroid-sparing

agent. More recently, high-dose IVIg, which is non-immunosuppressive, and

rituximab have been added to the therapeutic armamentarium.

Monitoring activity of disease

In the acute phase the progress of the

disease should be evaluated clinically. Once blistering stops and erosions

heal, changes in the titer of circulating pemphigus antibody (IIF test titers and ELISA values) may

help in guiding the dose of steroids. It should be monitored about every 6 months, and

should decrease with each measurement. Direct

immunofluorescence studies of normal skin have also been recommended to predict

remission or relapse. Laboratory monitoring is essential for

hematologic and metabolic indicators of glucocorticoid and/ or

immunosuppressive-induced adverse effects.

Topical

therapy

Patients who present with oral disease

and mild cutaneous involvement may remain in this localized phase for months.

Potent topical steroid such as clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream or

intralesional steroids may reduce the requirement for oral steroids. Topical

anticholinergic gel (pilocarpine gel) is reported to help healing of oral

erosions. Good oral hygiene, including treatment of periodontal disease, is

important.

Opportunist infection is the major

cause of death in patients with widespread blistering who are also

immunosuppressed. Potassium permanganate and topical antiseptics may help

reduce the risk of cutaneous infection, whilst topical imidazoles will reduce the

risk of oral candida.

Corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents

Systemic corticosteroid therapy,

usually in the form of oral prednisone, is the mainstay of therapy. Prednisone at 1 mg/kg/day (usually 60 mg/day) is a

typical initial dosage. Very-high-dose regimens (more than 120 mg/day)

provide no benefit over the low-dose regimens with respect to the frequency of

relapse or the incidence of complications.

The majority of

pemphigus vulgaris patients present with oral disease at an early and relatively

stable stage. The following regimen, also known as Lever's mini treatment

(LMT), is used. These patients may be controlled by starting prednisone 40 mg

on alternate days plus 100 mg azathioprine every day until there is complete

healing of all lesions. A gradual monthly and later bimonthly decrease of

prednisone was followed by the tapering of azathioprine, in a 1-year period.

The time required for the epithelialization of lesions varies between 4

and 7 months.

The combination

therapy of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and prednisone is reported to be an

effective treatment regimen to achieve rapid and complete control of

PV. For those patients who fail treatment with MMF and prednisone,

rituximab is an efficacious alternative therapy. Complete disease control is

achieved in 90% of patients using the following treatment algorithm.

If complete

remission is achieved with the combined therapy, the dosage of the

immunosuppressive drug is maintained while the prednisone is slowly tapered;

when a dose of 5–10 mg/day is reached, careful tapering of the

immunosuppressive drug is attempted. In young patients, the potential increase

in malignancies that might be associated with the use of these drugs must be

taken into account.

The dosage of prednisone is tapered to a level that controls

most disease activity. Attempts are made to use an alternate-day regimen to

minimize side effects. One taper method is to reduce prednisone by 10 mg every

week until the daily dose reaches 20 mg. Then the dose is reduced each

alternate week until a dose of 20 mg on alternate days is reached. Then the

dose reduction is slower until a final dose of 5 mg on alternate days is

achieved.

During the prednisone taper, the

immunosuppressive agent is continued at full dosage. The speed of the

prednisone taper is determined by the level of disease activity. It is not

necessary to have the disease totally suppressed before lowering the prednisone

dose.

In some

patients, especially those who are elderly with limited disease or those in

whom corticosteroids are contraindicated, immunosuppressive agents alone may be

used. Patients who fail to respond to

corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents can be treated with rituximab or

intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).

Immunosuppressive

drugs

Immunosuppressive

agents are given concomitantly for their glucocorticoid-sparing effect;

systemic steroids are routinely combined with other immunosuppressive drugs with

the expectation that other agent leads to a reduced total steroid dose,

increased remission rate and fewer side effects. These side effects include

infection, DM, osteoporosis, aseptic bone necrosis, thrombosis, cataract and

peptic ulcers.

The most commonly used agents are

mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide. One study showed that

mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine had similar efficacy,

corticosteroid-sparing-effects, and safety profiles as adjuvants during

treatment of pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus.

Mycophenolate mofetil

Mycophenolate mofetil

(1 g twice daily) has been reported to

be beneficial. It has a similar action to azathioprine, with less

myelosuppression but more gastrointestinal toxicity.

Adverse effects are gastrointestinal disorders (most common), genitourinary

complaints, increased incidence of viral or bacterial infection, and neurologic

symptoms. Relative contraindications include lactation, peptic ulcer disease,

hepatic or renal disease, and concomitant azathioprine or cholestyramine

therapy.

Azathioprine

Azathioprine, most frequently used agent. In the past, it was given in the

dose of 1.5- 2.5 mg/kg body weight. Today, the dose is adjusted based on

individual activity level for thiopurinemethyl transferase (TPMT), which should

be determined prior to initiating therapy. The onset of action of AZA is 4-6

weeks. The dose is continued at this level until the systemic steroids are

completely tapered and stopped. After 1-2 month of monotherapy, the dose is AZA

is tapered. If no new lesion occur and the circulating antibodies are no longer

detected, oral mucosal biopsy is taken once a dose of 50mg/day has been

reached. If the biopsy is negative, one can safely assume that the disease is

truly in remission and withdraw the agent. Azathioprine causes bone marrow suppression,

hepatotoxicity, and an increased risk of malignancy that is lower than that of

cyclophosphamide. Monitor blood cell counts and liver function tests.

Cyclophosphamide

Average starting dosage is 100 mg (1.1

to 2.5 mg/kg) per day. Cyclophosphamide “bolus” therapy with

500 mg IV given on day 1 of DCP along with mesna; during the interval 50mg

daily for the first 6 months is given.

Cyclophosphamide may be the most effective

drug but it is toxic. Side effects include bone marrow suppression, sterility, hemorrhagic

cystitis, bladder fibrosis, reversible alopecia, and an increased risk of

bladder carcinoma and lymphoma. Monitor urinalysis and blood cell counts.

Encourage oral fluid intake to decrease the risk of bladder fibrosis and

hemorrhagic cystitis.

Rituximab

Rituximab is a

potent B-cell-depleting chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, presumably targets B cells, the

precursors of (auto) antibody-producing plasma cells. CD20 is a transmembrane glycoprotein specifically expressed on B

cells (from the pre-B stage in the bone marrow to the activated and memory B

stage in blood or secondary lymphoid organs), but its expression is lost upon

plasma cell differentiation.

Rituximab seems not only to induce a depletion of CD20+ B cells and

a decline in IgG (including anti-desmoglein auto antibodies), but also

decreases desmoglein-specific T cells. When used as

adjuvant therapy, rituximab led to a complete remission in most of the patients

with refractory pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus. Two infusions of 1

g given on day 1 and day 15.

For maintenance: 500mg at 12 months and every 6 months thereafter to maintain

clinical remission or 1gm dose if clinical relapse occurs. Onset of action of rituximab is typically 8–16

weeks following the first infusion and improvement may persist for 12–18

months. The combination of rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulin is

effective in patients with refractory pemphigus vulgaris.

Adverse effects of rituximab in the treatment of

pemphigus appear uncommon. Because rituximab is a

chimeric biologic agent, patients may develop anti-drug antibodies that are

associated with infusion reactions and a lower therapeutic response.

Infection has been reported, and particular care needs to be taken to avoid

reactivation of viral hepatitis – patients should be rigorously screened prior

to treatment.

Veltuzumab, a humanized anti-CD20 antibody

which may be administered intravenously or subcutaneously, is reported to be an

effective treatment in an individual patient.

In the future,

desmoglein-specific immune suppression, via targeting T cells or B cells, needs

to be developed. Recently, for example, the possibility of using modified CAR

(chimeric antigen receptor) therapy to target Dsg3-specific B cells was

proposed. Such approaches would represent an ideal therapeutic strategy given

that the target antigens and pathophysiological mechanisms of pemphigus have

been well characterized.

Intravenous immunoglobulin

High-dose IVIg is

another option for resistant disease. IVIg is a blood product prepared from

pooled plasma that has immunomodulatory effects when used in a high dose. It is

thought to exert its effect via multiple modes of action, including modulation

of expression and function of Fc receptors and the cytokine network; provision

of anti-idiotypic antibodies; and modulation of dendritic cell, T-cell and

B-cell activation, differentiation and effector functions. High-dose intravenous

immunoglobulin (400

mg/kg/day for 5 consecutive days) in a single cycle is an effective and safe

treatment for patients with pemphigus who are relatively resistant to systemic

steroids.

Management of blisters

1.

Gently cleanse blister with antimicrobial

solution, taking care not to rupture

2.

Pierce blister at base with a sterile needle,

with the bevel facing up. Select a site in which the fluid will drain out by

gravity to discourage refilling

3.

Gently apply pressure with sterile gauze

swabs to facilitate drainage and absorb fluid

4.

Do not de-roof the blister

5.

After fluid has drained, gently cleanse again

with an antimicrobial solution

6.

It may be necessary to apply a non adherent

dressing

7.

Some large blisters may need a larger hole to

drain properly – use a larger needle and pierce more than once

8.

Many patients report pain or a burning

sensation during blister care; offer analgesia prior to the start of the

procedure

9.

Document on blister chart the number and

location of new blisters

Course and remission

It is possible to eventually induce complete

and durable remissions in most patients with pemphigus that permit systemic

therapy to be safely discontinued without a flare in disease activity. The

proportion of patients in whom this can be achieved increases steadily with

time, and therapy can be discontinued in approximately 75% of patients after 10

years.

Determining remission and when

to stop treatment

Treatment is stopped when patients are

clinically free of disease and when they have a negative finding on direct

immunofluorescence. The titers of circulating antibodies have a rough

correlation with disease activity, but they are not accurate enough to

determine when to stop therapy. A skin biopsy for direct immunofluorescence can

predict when a patient is in remission and may be used to predict relapse. A

negative direct immunofluorescence finding suggests that there is immunologic

remission, and 80% of patients with a negative direct immunofluorescence study

remained disease free for the next 5 years.

Pemphigus Foliaceus

When pemphigus foliaceus is active and widespread, the

treatment is, in general, similar to that for pemphigus vulgaris. In some

patients, pemphigus foliaceus may be localized for many years; they do not

necessarily have to be treated with systemic therapy, and super potent topical

corticosteroids may be sufficient to control the disease. The combination of

nicotinamide (1.5 gm/day) and minocycline (100 mg twice a day) may be an

effective alternative to steroids in pemphigus foliaceus. Dapsone can also be used when neutrophils are dominant

histologically.

Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

Patients with benign tumors, such as thymomas or localized

Castleman's disease, should have the tumor surgically excised. The majority of

these patients will either improve substantially or clear completely. However,

it may take 6–18 months to see complete resolution of lesions after excision of

a benign neoplasm. In patients with malignant neoplasms, there is no consensus

on a standard effective therapeutic regimen. Administration of tumor-specific

chemotherapy may result in complete resolution of the malignancy and a slow

resolution of the skin lesions. Cutaneous lesions respond more rapidly to

therapy, in contrast to the stomatitis, which is generally refractory to most

forms of treatment. Overall, the prognosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus is poor

due to its resistant nature to treatment.

IgA Pemphigus

Dapsone is the drug of choice for most patients with IgA

pemphigus. A clinical response usually occurs within 24–48 hours. If dapsone is

not well tolerated, sulfapyridine and acitretin are useful alternatives.

Occasionally, those drugs are not effective, and low- to medium-dose prednisone

may be considered, as well as photo chemotherapy (PUVA) or colchicine.