Erythema multiforme

Salient features

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction

Erythema

multiforme (EM) is an acute, self-limited, usually mild, and often relapsing

mucocutaneous syndrome

resulting from cell‐mediated hypersensitivity reaction most commonly to

infection, less

commonly to drugs, characterized by the abrupt onset

of symmetric fixed red papules, some of which evolve into typical and/or

occasionally “atypical” papular target lesion. Most cases are

related to infections (herpes simplex virus [HSV] (facial or genital) and Mycoplasma

pneumoniae). Medications are not a common cause, in

contrast to the spectrum of drug-induced epidermal necrolysis. Two forms of EM are recognized

– EM minor and EM major. Both are characterized by the same type of elementary

lesions (targets), but are distinguished by the presence or absence of mucosal

involvement and systemic symptoms.

Erythema Multiforme

Subtypes

|

·

Erythema multiforme minor: EMm C/F:

typical targets, acral skin and lip involvement, no mucosal erosions. Associated

etiology: HSV, other infections ·

Erythema multiforme major: EMM C/F:

typical targets, acral skin involvement, mucosal erosions of at least two

mucosal sites Associated

etiology: HSV, other infections ·

Atypical EMM C/F:

giant targets, central distribution, prominent mucosal erosions. Associated

etiology: mycoplasma pneumonia, HSV ·

Mucosal EMM C/F: no

skin involvement, prominent mucosal erosions. Associated

etiology: mycoplasma pneumonia. ·

Continuous or persistent EM C/F:

typical targets, acral skin involvement, few mucosal erosions, overlapping

recurrences Associated etiology: HSV,

idiopathic |

Epidemiology

Age of Onset

50% is under 20 years.

Sex

More frequent in males than in females.

Etiology

The etiology of EM is

unclear in most patients, but appears to be an immunological hypersensitivity

reaction with the appearance of cytotoxic effector cells (CD8+ T lymphocytes)

in the epithelium, inducing apoptosis of scattered keratinocytes and leading to

satellite cell necrosis.

Predisposing factors

There may be a genetic

predisposition, with associations of recurrent EM with HLA‐B15 (B62), HLA‐B35,

HLA‐A33, HLA‐DR53

and HLA‐DQB1*0301. HLA‐DQ3

has been proven to be especially related to recurrent EM and may be a helpful

marker for distinguishing this herpes‐associated EM from other

diseases with EM‐like lesions. Patients with extensive mucosal

involvement may have the rare HLA allele DQB1*0402.

Triggering factors

In

up to half of cases, there is no known provoking factor. The most common

association is with a preceding herpes simplex infection (facial or genital) or

with a Mycoplasma infection, especially when conjuctival and

corneal involvement occurs; other viral or bacterial infections and vaccination

have also been incriminated

The

reaction is triggered by the following:

- Infective agents, particularly HSV (herpes‐associated EM), which is implicated in 70% of recurrent EM. Bacteria (Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and many others), other viruses, fungi or parasites are less commonly implicated.

- Drugs such as sulphonamides (e.g. co‐trimoxazole), cephalosporins, aminopenicillins, quinolones, barbiturates, oxicam non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, anticonvulsants, protease inhibitors, allopurinol and many others may trigger severe EM or toxic epidermal necrolysis in particular.

- Food additives or chemicals such as benzoates, nitrobenzene, perfumes, terpenes.

- Immune conditions such as bacilli Calmette–Guérin (BCG) or hepatitis B immunization, sarcoidosis, GVHD, inflammatory bowel disease, polyarteritis nodosa or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

- Idiopathic probably also due to undetected herpes simplex or Mycoplasma.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of erythema

multiforme (EM) is still not completely understood, but it is probably

immunologically mediated and appears to involve a hypersensitivity reaction

that can be triggered by a variety of stimuli, particularly viral, bacterial,

or chemical products.

Cell-mediated immunity

appears to be responsible for the destruction of epithelial cells. Early in the

disease process, the epidermis becomes infiltrated with CD8 T lymphocytes and

macrophages, whereas the dermis displays a slight influx of CD4 lymphocytes.

These immunologically active cells are not present in sufficient numbers to be

directly responsible for epithelial cell death. Instead, they release

diffusible cytokines, which mediate the inflammatory reaction and resultant

apoptosis of epithelial cells. In some patients, circulating T cells

transiently demonstrate (for < 30 d) a T-helper cell type 1 (TH1) cytokine

response (interferon [IFN] gamma, tumor necrosis factor [TNF] alpha,

interleukin [IL] 2). Results of immunohistochemical analysis have also shown

lesion blister fluid to contain TNF, an important proinflammatory cytokine.

In

the majority of children and adults with EM, the disease is precipitated by HSV

types 1 and 2. Preceding herpes labialis is noted in ~50% of patients with EM.

Herpes labialis may precede the onset of the cutaneous lesions, occur

simultaneously, or be evident after the target lesions of EM have appeared.

Most commonly, herpes labialis precedes target lesions of EM by 3–14 days. It

is presumed that most cases in children and young adults are due to HSV type 1,

but documented cases of HSV type 2 in adolescents and young adults have been

reported.

Not

only are HSV-encoded proteins found within affected epidermis, but HSV DNA can

be detected within the early red papules or the outer zone of target lesions in

80% of individuals with EM. The presence of fragments of HSV DNA (most often

comprised of sequences that encode its DNA polymerase) within the cutaneous

lesions, as well as the expression of virally encoded antigens on

keratinocytes, may be interpreted as evidence for replicating HSV within

affected skin sites. However, replication must be at a low level, because

usually HSV cannot be cultured from EM lesions.

The

inflammation within cutaneous lesions is believed to be a part of an

HSV-specific host response. Individuals with HSV-associated EM have normal

immunity to HSV, but may have difficulty clearing the virus from infected

cells; within sites of cutaneous lesions, HSV DNA may persist for 3 months

after a lesion has healed. Development of cutaneous lesions is initiated by the

expression of HSV DNA sequences within the skin, followed by the recruitment of

virus-specific T helper type 1 (Th1) cells that produce interferon-γ in response to viral antigens within the skin.

An “autoimmune” response is then thought to result from the recruitment of T

cells that respond to autoantigens released by lysed/apoptotic viral

antigen-containing cells. More recently it was shown that the HSV DNA fragments

are transported (by peripheral blood CD34+ Langerhans

cell precursors) to the sites where EM skin lesions will develop prior to each

eruption.

While

HSV is the predominant cause of EM, there are other associated infectious

agents. In particular, a severe acro-mucosal presentation with mucositis,

conjunctivitis, and targetoid or bullous skin eruptions can be seen in patients

with M. pneumoniae infections,

primarily community-acquired pneumonia. This variant occurs most commonly in young

boys and adolescents. M. pneumoniae has

been cultured from the bullae in patients with EM-like skin reactions,

suggesting an etiologic role.

Clinical features

Clinical criteria allow the distinction of

both forms of EM from SJS/TEN in the vast majority of patients. These clinical

criteria are as follows: (1) the type of elementary skin lesion; (2) the

distribution of skin lesions (topography); (3) the presence or absence of overt

mucosal lesions; and (4) the presence or absence of systemic symptoms.

|

COMPARISON OF ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME (EM) MINOR, EM MAJOR AND

STEVENS–JOHNSON SYNDROME (SJS) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Type of skin lesions |

Distribution |

Mucosal involvement |

Systemic symptoms |

Progression to TEN |

Precipitating factors |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

EM minor |

|

|

Absent or mild |

Absent |

No |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

EM major |

|

|

Severe |

Present |

No |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

SJS |

|

|

Severe |

Present |

Possible |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Elementary skin lesion

The

characteristic elementary skin lesion of EM is the typical target lesion.

The latter measures <3 cm in diameter, has a regular round, circle shape papule

or plaque and a well-defined border, and it consists of at least three distinct

concentric zones: (1) a central area of dusky erythema or purpura; that has

evidence of damage to the epidermis (2) a middle paler zone of edema; and (3) an

outer ring of erythematous halo. The central area may be bullous. Over time,

the lesion may resemble a “bull’s eye”.

While

early target lesions often have a central dusky zone and a red outer zone

(“iris” lesion), they can evolve to three zones of color change. The

individual lesions begin as sharply marginated, erythematous macules, which

become raised, edematous papules over 24–48 h. The lesions may reach several centimeters

in diameter. Typically, a ring of erythema forms around the periphery, and

centrally the lesions become flatter, purpuric, and dusky, they can evolve to classic

“target” lesion with three zones of color change. Each concentric ring within

the target lesion most likely represents one of a sequence of events of the

same ongoing pathologic process. This may explain why

some patients have only a limited number of fully developed, typical targets

amidst a number of target lesions that are not yet typical or fully evolved,

while in others all the lesions are at the same stage of development, thus

creating a monomorphic clinical appearance. Given the possibility that only a

few typical target lesions may be present, a complete skin examination is

essential.

In

EM, elevated atypical papular target lesions can either accompany

typical target lesions or constitute the primary cutaneous lesion. Raised

atypical target lesions are ill-defined, round, palpable lesions with only two

zones including a central raised edematous area with an erythematous border. They

must be distinguished from the flat (macular) atypical targets that are seen in

SJS or TEN, but not EM. The latter are defined as round lesions, but with only

two zones and/or a poorly defined border, as well as being non-palpable (with

the exception of a potential central vesicle or bulla).

Distribution of skin lesions (topography)

Although

there is considerable variation from individual to individual, numerous lesions

are usually present. In general, lesions of EM develop preferentially on the extremities

and the face; target lesions favor the upper extremities, as does the entire eruption of EM. Typical

targets are best observed on the palms and soles. Lesions often first appear

acrally and then spread centripetally in a symmetric distribution, with

initial involvement most frequently on the dorsal hands.

The dorsal feet,

extensor aspect of the forearms, elbows, knees, palms and soles typically

become involved, less commonly the face.

In about 10% of cases, more widespread lesions occur on the trunk. Often

the hands are selectively involved. Thus, the typical distribution is acral. In

addition, lesions tend to be grouped, especially on the elbows or knees

The

Koebner phenomenon may be observed, with target lesions appearing within areas of

cutaneous injury such as scratches or within areas of sunburn. The injury must precede the onset of the EM eruption

because the Koebner phenomenon does not occur once the EM lesions have

appeared. Although patients occasionally report burning and itching, the eruption

is usually asymptomatic.

Predilection sites and distribution of EM

Mucous Membrane Lesions

Most patients with EM

(70%), of either minor or major forms, have oral lesions. The oral mucosa may

be involved alone or in association with skin lesions. EM minor affects one

mucosa and EM major affects two or more mucous membranes.

Predilection sites for mucosal

lesions are the lips, on both cutaneous and mucosal sides, non attached

gingivae, and the ventral side of the tongue. The hard palate is usually

spared, as are the attached gingivae. On the cutaneous part of the lips,

identifiable target lesions may be discernible. On the mucosa proper, lesions begin as erythematous areas that blister

and break down to irregular extensive painful erosions with extensive

surrounding erythema. The labial mucosa is often involved, and a serosanguinous

exudate leads to crusting of the swollen lips. The process may rarely extend to

the throat, larynx, and even the trachea and bronchi.

Eye

involvement begins with pain and bilateral conjunctivitis in which vesicles and

erosions can occur. In children, ocular lesions appear to be more frequent and

more severe in M. pneumoniae- associated cases.

Mucosal erosions plus

typical or atypical raised targets and epidermal detachment involving less than

10% of the body surface and usually located on the extremities and/or the face

characterize herpes simplex‐induced EM major.

Mucosal erosions plus

widespread distribution of flat atypical targets or purpuric macules and

epithelial detachment involving less than 10% of body surface on the trunk,

face and extremities are characteristic of drug‐induced

Stevens–Johnson syndrome.

Systemic

symptoms

Systemic

symptoms are almost always present in EM major and absent or limited in EM

minor. In EM major, the systemic symptoms that usually precede and accompany

the skin lesions are fever and asthenia of varying

degrees. Arthralgias with joint swelling have occasionally been

described, as has pulmonary involvement resembling atypical pneumonia. Whether

the latter is a pulmonary manifestation of EM versus one of the associated

infections such as M. pneumoniae is unclear. Renal, hepatic and hematologic abnormalities

in the context of EM major are rare.

Clinical types

Mild

Forms (EM Minor)

This accounts for

approximately 80% of cases. Mucous membranes are usually spared or minimally

affected, and often limited to the lip. Vesicles may be present but no bullae or systemic symptoms.

Eruption usually confined to extremities and face. Typical EM minor is

usually associated with a preceding orolabial HSV infection. HAEM lesions

appear 1–3 weeks (average 10 days) after the herpes outbreak. The majority of

idiopathic cases of EM minor are associated with recurrent HSV infections, and

patients may be successfully treated with suppressive antiviral regimens.

Localized vesiculobullous form

This form is

intermediate in severity. The skin lesions present as erythematous macules or

plaques, often with a central bulla and multiple concentric

vesicular rings

(herpes iris of Bateman). Mucous membranes are quite often involved. In this

type, the skin lesions tend to occur in the classic acral distribution, but may

be few in number. This pattern may be

more frequent in Mycoplasma pneumoniae-related cases of atypical EMM.

Severe Forms (EM Major)

This is a severe illness

associated with more extensive target lesions and mucous membrane involvement.

The onset is usually sudden, although there may be a prodromal systemic illness

of 1–13 days before the eruption appears.

It occurs in all ages, is centered on the extremities and face,

but more often than EM minor may include truncal lesions; severe, extensive,

tendency to become confluent and bullous, positive Nikolsky sign in

erythematous lesions. It typically shows a cockade-like erythema on the

extensor surface of the extremities as well as trunk involving less than 10% of

the body surface area. Mucous

membrane disease is prominent and often involves not only the oral mucosa and

lips, but the genitalia and ocular mucosa as well. EM major is associated with Mycoplasma infections, although minority

may result from herpes simplex and reaction to drugs.

Fuchs syndrome is a clinical

variant of EMM, with exclusive involvement of conjunctivae and oral mucosa

Generalized EMM with

cockade-like erythema

Fuchs syndrome: Extensive erosions of the

conjunctiva and the oral mucosa without involvement of other skin

Rowell syndrome

This syndrome comprises lupus erythematosus associated with EM‐like skin lesions, and immunological findings

of speckled antinuclear antibodies, anti‐La or anti‐Ro

antibodies, and a positive test for rheumatoid factor

Natural

history

In

EM, a history of an abrupt onset of skin lesions is obtained, with almost all

of the lesions appearing within 24 hours and full development by 72 hours and the

individual lesions remain fixed at the same site for 7 days or longer. Often there are a limited number

of lesions, but up to hundreds may form. In most cases, EM affects well under 10% of the

body surface area.

For

most individuals with EM, the episode lasts 2 weeks and heals without sequelae;

one possible rare exception is ocular sequelae in the setting of EM major,

which may occur if adequate eye care is not promptly instituted. Occasionally,

post-inflammatory hyper- or hypopigmentation is seen. Patients with EM usually

have an uncomplicated clinical course, although recurrences, in the case of

HSV-associated EM, are quite common. Most individuals with recurrent

HSV-associated EM have one or two episodes a year, an exception being those

receiving immunosuppressive drugs such as oral corticosteroids which may be

associated with more frequent and longer episodes of EM. These individuals may

have five or six episodes per year or even almost continuous disease in which

one attack has not completely resolved before another occurs. The incidence of

secondary bacterial infections also increases in the setting of prolonged

corticosteroid use.

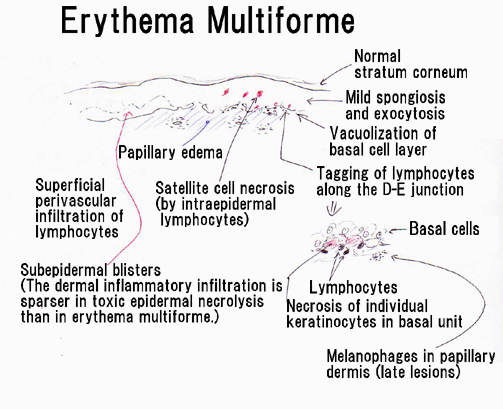

Pathology

EM

is a clinicopathologic, not a purely histologic, diagnosis. Histologic findings

are characteristic, but not specific, and are most useful for excluding

entities in the differential diagnosis such as lupus erythematosus (LE) and

vasculitis.

In EM, the keratinocyte is the target of the inflammatory insult, with

apoptosis of individual keratinocytes being the earliest pathologic finding. Early lesions of EM exhibit

lymphocyte accumulation at the dermal–epidermal interface, with exocytosis into

the epidermis, lymphocytes attached to scattered necrotic keratinocytes

(satellite cell necrosis), spongiosis, vacuolar degeneration of the basal cell

layer, and focal junctional and subepidermal cleft formation. The papillary

dermis may be edematous and a dense perivascular infiltrate

of lymphocytes is also present, which is more abundant in older lesions. The

vessels are ectatic with swollen endothelial cells; there may be extravasated

erythrocytes and eosinophils. Immunofluorescence findings are negative or nonspecific.

In advanced lesions subepidermal blister formation may occur, but necrosis

rarely involves the entire epidermis. In late lesions, melanophages may be

prominent.

Specific

HSV antigens have been detected within lesional keratinocytes by immunofluorescence,

and HSV genomic DNA has been detected by PCR amplification of skin biopsy

specimens.

Compared

to SJS, the dermal inflammation component is more prominent in EM and the

epidermal “necrolysis” component is more discrete. Large areas of full-thickness

epidermal necrosis are not seen in EM.

|

DIFFERENCES

BETWEEN URTICARIA AND ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME |

|

|

Urticaria |

Erythema

multiforme |

|

Central

zone is normal skin |

Central

zone is damaged skin (dusky, bullous or crusted) |

|

Lesions

are transient, lasting less than 24 hours |

Lesions

“fixed” for at least 7 days |

|

New

lesions appear daily |

All

lesions appear within first 72 hours |

|

Associated

with swelling of face, hands or feet (angioedema) |

No edema |

DIAGNOSIS

The target-like lesion and the symmetry are quite typical.

Treatment

Treatment of

EM is determined by its cause and extent. Therapeutic

options include topical and systemic treatment of the acute eruption as well as

prophylactic treatment of recurrent disease. EM minor is

generally related to HSV, and prevention of herpetic outbreaks is central to

control of the subsequent episodes of EM. A sunscreen lotion and

sunscreen-containing lip balm should be used daily on the face and lips to

prevent ultraviolet (UV) B-induced outbreaks of HSV. If this does not prevent

recurrences or if genital HSV is the cause, chronic suppressive doses of an

oral antiviral drug for at least 6 months with oral acyclovir

(10 mg/kg/day in divided doses), valacyclovir (500–1000 mg/day, with

dose depending upon frequency of recurrences) or famciclovir (250 mg twice

daily) should be considered. This will prevent recurrences in

up to 90% of HSV-related cases, occasionally the beneficial effect can

continue even after the antiviral drug is discontinued. As a rule, antiviral

therapy has minimal impact if given after the appearance of the acute episode

of EM. It is of interest that some patients who suffer from recurrent erythema

multiforme without overt herpes infection are helped by prophylactic acyclovir,

implying that recurrent herpes infection may nevertheless be responsible.

In patients

whose condition fails to respond adequately to antiviral suppression, dapsone,

cyclosporine, or thalidomide may occasionally be helpful. It should be noted that

most cases of EM minor (HAEM) are self-limited and symptomatic treatment may be

all that is required. Oral antihistamines for 3 or 4 days may

reduce the stinging and burning of the skin. Tetracycline is indicated in EM related to Mycoplasma

pneumoniae.

In extensive

cases of EM minor, systemic steroids have been used, but because they

theoretically may reactivate HSV, they are best given concurrently with an

antiviral drug. The response to systemic corticosteroids is often

disappointing. For patients with widespread EM unresponsive to the above therapies,

management is as for severe drug induced SJS.

When a precipitating factor can be identified

(e.g. HSV or M. pneumoniae), specific therapy should be instituted. In severe

forms of EM with functional impairment, early therapy with systemic

corticosteroids at an initial dosage of prednisone [0.5–1 mg/kg/day for

3-5 days]or pulse methylprednisolone [20 mg/kg/day for 3 days]) should be

considered, despite the absence of controlled studies and the long-existing controversy

regarding increasing the risk of infectious complications.

Regarding oral EM, spontaneous healing can be

slow, up to 2–3 weeks in EM minor and up to 6 weeks in EM major. No specific

treatment is available but supportive care is important; a liquid diet and

intravenous fluid therapy may be necessary. Electrolytes and nutritional

support should be started as soon as possible. Oral hygiene should be improved

with 0.2% aqueous chlorhexidine mouth baths. EM minor often responds to topical “swish and spit” mixtures containing

lidocaine, benadryl, and kaolin. Unresponsive cases may respond to topical corticosteroids, although

systemic corticosteroids may still be required. EM major should be treated with

systemic corticosteroids (prednisolone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day tapered over 7–10 days)

and/or azathioprine or other immunomodulatory drugs.

Administration of topical ophthalmic

preparations should be done in conjunction with an ophthalmologist.