Pregnancy dermatoses

Introduction

The dermatoses of pregnancy

are all associated with severe pruritus. The diagnoses of pemphigoid gestationis

and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy are confirmed by immunofluorescence

and laboratory findings respectfully.

Polymorphic and atopic eruptions of pregnancy are distressing only to

the mother. Pemphigoid gestationis may be associated with prematurity and

small-for-gestational age babies, and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

increases the risk for fetal distress, premature labour, and stillbirth.

Corticosteroids and antihistamines control pemphigoid gestationis as well as

polymorphic and atopic eruptions of pregnancy. Intrahepatic cholestasis of

pregnancy is treated with ursodeoxycholic acid.

Summary of

Dermatoses of Pregnancy

|

Morphology |

Distribution |

Usual Onset |

Fetal Risk |

|

|

|

Pemphigoid

(herpes) gestationis |

Urticarial

papules and plaques progress to vesicles and bullae |

Begins on trunk,

then progresses to generalized eruption Spares face,

mucus membranes, palms, soles |

Second or third

trimester, or immediately postpartum |

Small-for-gestational

age births Preterm delivery Neonatal

pemphigoid gestationis |

|

|

Intrahepatic

cholestasis of pregnancy |

Excoriations and

excoriated papules ± jaundice |

Localized to

palms and soles or generalized |

Third trimester |

Preterm delivery Fetal distress Fetal death |

|

|

Pustular

psoriasis of pregnancy |

Erythematous

patches with subcorneal pustules at their margins |

Begins in

flexures Generalizes

demonstrating centrifugal spread |

Third trimester |

Placental

insufficiency may lead to stillbirth or neonatal death |

|

|

Pruritic

urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy |

“Polymorphous”

including urticarial papules and plaques ± vesicles |

Begins within

abdominal striae Spreads to

remainder of trunk and then extremities Spares umbilicus |

Third trimester

or immediately postpartum |

None |

|

|

E-type Atopic

eruption of pregnancy |

Eczematous

patches and plaques |

Face, neck,

chest, flexural extremities |

Second or third

(less commonly) trimester |

None |

|

|

P-type Atopic

eruption of pregnancy |

Excoriated or

crusted papules |

Extremities,

occasionally trunk |

Second or third

(less commonly) trimester |

None |

NA = not applicable.

|

DERMATOSES OF PREGNANCY – FETAL RISK, INVOLVEMENT OF

NEWBORN SKIN, AND RISK OF RECURRENCE |

|||

|

Dermatosis |

Fetal risk |

Newborn skin

involvement |

Risk of recurrence |

|

Pemphigoid gestationis |

Increased risk of

prematurity and small-for-gestational age neonates; risk correlates with

disease severity |

Mild and transient

lesions of pemphigoid gestationis in up to 10% |

Commonly recurs

(“skipped” pregnancies in only 5–8% of women); recurrences induced by oral

contraceptives in 25–50% |

|

Polymorphic eruption

of pregnancy |

None |

None |

Usually does not recur |

|

Intrahepatic

cholestasis of pregnancy |

Increased risk of

premature labor (20–60%), intrapartal fetal distress (20–30%), and

stillbirths (1–2%) |

None |

Recurrence in 45–70%

of subsequent pregnancies; may be triggered by oral contraceptives |

|

Atopic eruption of

pregnancy |

None |

None |

Commonly recurs due to

atopic diathesis |

Dermatoses Not Associated with Fetal Risk in Pregnancy

At a Glance

|

·

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of

pregnancy is a common, self-limited, intensely pruritic dermatosis that

occurs almost exclusively in primigravidas during late pregnancy. The term polymorphic

eruption of pregnancy appropriately encompasses the wide spectrum of

clinical presentations. ·

Atopic eruption of pregnancy represents a newly

introduced complex comprising pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy, prurigo of

pregnancy, and eczema of pregnancy. Lesions typically appear before the third

trimester and may resemble classic atopic dermatitis (AEP, E-type) or be

papular (AEP, P-type). |

Polymorphic

eruption of pregnancy

Salient

features

·

Urticarial papules and plaques that usually first appear within

striae distensae during the latter portion of the third trimester or

immediately postpartum

·

Development of polymorphous features (vesicles, erythema,

target, and eczematous lesions) with disease progression

·

Most frequent in primiparous women

·

Nonspecific histologic features, negative IF, and normal routine

laboratory evaluation

·

No maternal or fetal risks; usually does not recur

Introduction

Polymorphic

eruption of pregnancy is a common, benign, self‐limiting,

intensely pruritic inflammatory disorder that occurs almost exclusively in primigravidae

(76%) and begins late in the third trimester of

pregnancy (mean onset, 35 weeks) or occasionally in the early postpartum period.

It is characterized by a typical

clinical presentation, normal laboratory tests, and negative IF or ELISA.

Epidemiology

Its

incidence is about 1: 160 pregnancies. It is seen predominantly in

primiparous women and tends not to recur in subsequent pregnancies. There is

neither an autoimmune diathesis nor an association with a specific HLA type.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of PEP remains unclear. The main theories

proposed focus on abdominal distension and hormonal and immunological factors. It has

therefore been suggested that rapid, late stretching of abdominal skin may lead

to damage of connective tissue with altered collagen and/or elastic fibers and

elicitation of an allergic-type reaction, resulting in the initial appearance

of the eruption within striae. The lesions then become generalized as the

inflammatory response develops cross-reactivity to collagen in otherwise

normal-appearing skin. Immune tolerance during subsequent pregnancies might

prevent recurrence. Increased

progesterone receptor immunoreactivity has been detected in

lesional PUPPP, leading some to posit a role for progesterone activation of

keratinocytes.

Clinical

features

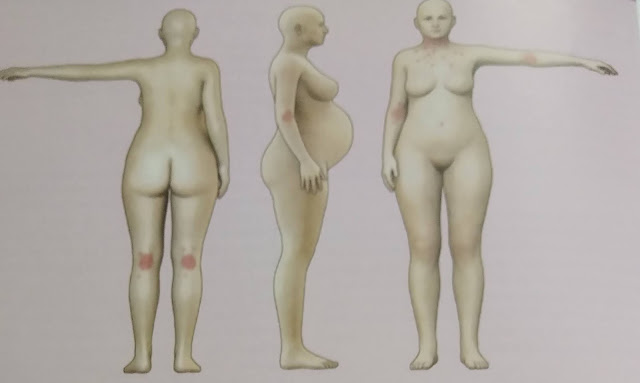

Typical distribution of PEP

Onset is most

often during the latter part of the third trimester (85%), usually 1 to 2 weeks before delivery or in

the immediate postpartum period (15%). The earliest lesions are severely pruritic 1- to 2-mm, erythematous, urticarial papules

surrounded by a narrow pale halo. The papules coalesce to form erythematous edematous urticarial

plaques with polycyclic shape and arrangement. The eruption appears suddenly,

begins on the abdomen in 90% of patients, classically within the striae gravidarum, and

demonstrates periumbilical sparing. Skin lesions are extremely pruritic, causing

sleepless nights and great stress, yet excoriations are infrequent. After a few days, rapid spread of eruption in a symmetric

fashion to the proximal

thighs, buttocks, lower

back, breasts,

and upper

inner arms is the

norm. Involvement of the palms, soles, or skin above the breast is exceptional.

There

are no mucous membrane lesions. While pruritic

urticarial papules are the initial lesions in almost all patients,

approximately half will develop more polymorphic features as the disease

evolves, including widespread non‐urticated erythema, erythema

multiforme–like target lesions, tiny vesicles,

(1–2 mm in size; never bullae), and

eczematous plaques. Irrespective of whether the eruption starts during

pregnancy or postpartum, lesions resolve over an average of 6 weeks, independently of delivery.

Disease

course and fetal prognosis

Maternal

and fetal prognosis is unimpaired and there is no cutaneous involvement of the

newborn. Lesions are self‐limiting and recurrences in subsequent pregnancies or with

exposure to oral contraceptives are unusual. Spontaneous remission within days

of delivery is the rule.

Differential Diagnosis

Since lesions of PEP may show

microvesiculation, contact dermatitis must be considered. Drug eruptions,

urticaria, or viral exanthems may also be in the clinical differential

diagnosis. The most important entity to exclude is urticarial pemphigoid gestationis,

whose lesions tend to appear earlier during gestation, have no association with

abdominal striae and often involve the umbilicus, along with positive IF of

perilesional skin.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is generally made

clinically when patient presents with the eruption in typical locations at the

end of pregnancy. Biopsy should be performed if PG is being considered in the

differential diagnosis. The histopathology of this

condition is non‐specific. Epidermal changes vary from modest

spongiosis to acanthosis with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, depending upon

the stage of the disease. The dermis shows a nonspecific perivascular

lymphocytic infiltrate with a variable degree of dermal edema and a variable

number of neutrophils or eosinophils. Early lesions may resemble arthropod bite

reactions,

with a superficial and deep perivascular and

interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate within the dermis. Numerous

eosinophils are also present and an absence of epidermal changes.

The histologic correlate of microvesiculation is

severe epidermal spongiosis and/or dermal edema.

Direct

and Indirect immunofluorescence is generally negative.

Treatment

Although harmless to the mother and fetus, pruritus is often intense and

unremitting. Symptomatic treatment with topical

corticosteroids and emollients, with or without antihistamines, is usually

sufficient to control pruritus and skin lesions. In severe generalized cases, a

short course of systemic corticosteroids (prednisolone starting at 40–60 mg/day

and tapering to zero over a few weeks)

relieves

symptoms in 24 h. Early induction of labor can also be

considered if the patient is close to term.

Treatment ladder

First line

·

Topical emollients: aqueous cream +

1–2% menthol

·

Topical corticosteroids

·

Oral antihistamines: loratadine and

cetirizine

Second line

·

Prednisolone

Consider early induction of labor if patient is close to term

Atopic eruption of

pregnancy (AEP)

Salient

features

·

Eczematous and/or papular skin lesions in a patient with an

atopic diathesis in whom other specific dermatoses have been excluded

·

Most common pruritic disorder during pregnancy

·

Generally appears earlier than other pregnancy-related

dermatoses (75% before the third trimester)

·

Nonspecific histology; negative direct IF; elevated serum IgE

levels in up to 70% of patients

·

No maternal or fetal risks; commonly recurs in subsequent

pregnancies

Introduction

Atopic

eruption of pregnancy (AEP) is defined as a

benign pruritic disorder of pregnancy characterized by either

an exacerbation or the first occurrence of eczematous (AEP, E-type) and/or papular

(AEP, P-type) skin changes during pregnancy in patients

with an atopic diathesis. As the majority of patients belong to the

second group, the atopic

link is often overlooked, leading to a number of different diagnoses, as

evidenced by the many synonyms.

AEP comprises about 50% of all

pregnancy dermatoses.

It

usually starts before the third trimester, and a tendency to recur in

subsequent pregnancies.

Epidemiology

AEP is by far the

most common pruritic disorder in pregnant women and it tends to appear earlier

than the other pregnancy-related dermatoses. Its incidence is not known but may

be as high as 1 in 5 to 1 in 20.

Risk factors

Risk factors for AEP include a

personal and /or family history of atopy.

Pathogenesis

AEP is thought to be triggered by pregnancy-‐specific shifts in cytokine profile expression leading to

preferential expression of T-helper 2 cytokines. To prevent fetal

rejection, a normal pregnancy is characterized by a lack of strong maternal

cell-mediated immune function and reduced Th1 cytokine production (e.g. IL-12,

interferon-γ) in contrast to the dominant

humoral immune response with increased Th2 cytokine production (e.g. IL-4,

IL-10). This natural switch towards a dominant Th2 response, which worsens the

imbalance already present in most atopic patients, is thought to favor the

development of AEP i.e. exacerbation of pre‐existing

atopic eczema and the first manifestation of atopic skin changes.

Clinical

features

Typical distribution of E-type AEP

In contrast to the

other specific dermatoses of pregnancy, AEP appears earlier, often during the

first trimester, with 75% of patients presenting before the third trimester. 20% patients suffer from an exacerbation of pre‐existing

atopic eczema with a typical clinical picture while remaining 80% experience

atopic skin changes for the first time. Of these, two‐thirds

present with widespread eczematous changes (so‐called E‐type

AEP) often affecting typical atopic sites such as the face, neck and flexural

surfaces of the limbs; one‐third of patients have papular

lesions (P‐type AEP) and would previously have been classified as prurigo of pregnancy.

Papular or P-type lesions are either scattered small

erythematous papules or

discrete, excoriated prurigo papules with a predilection for extensor surfaces

of the limbs, with truncal involvement less common as well as typical prurigo nodules, mostly located on the

shins and arms. Minor

features of eczema, including xerosis (often marked) or hyperlinear palms, may

be noted in patients with either subtype.

Disease

course and prognosis

Lesions respond quickly to therapy; however,

recurrence with subsequent pregnancies is common, consistent with an atopic

diathesis. Maternal and fetal prognoses are excellent, even in severe cases. In

a mother with a known history of atopy, the

infant may be at risk of developing atopic skin changes later on. In a mother with no prior history

of eczematous eruption, her risk of recurrence outside of pregnancy is unknown.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is

largely clinical as histopathologic features are nonspecific. Direct and

indirect immunofluorescence

studies are negative. Total serum IgE is elevated in up to 70% of individuals

with AEP, usually to a mild degree. Serologic tests reveal no other

abnormalities.

Differential Diagnosis

Of the specific pregnancy dermatoses, PEP and

ICP are the ones that in particular need to be excluded. In AEP, the eruption

starts significantly earlier during gestation and has no association with

striae; serum bile acid levels are also normal. Furthermore, other pruritic

dermatoses not specifically associated with pregnancy (e.g. scabies, viral

exanthems, drug eruptions) must be considered.

Treatment

Cutaneous

lesions respond rapidly to mid potency

topical corticosteroids with or without systemic antihistamines. Emollients,

humectants, and topical antipruritic agents also play a role, as they do in

non-pregnant patients with atopic dermatitis. Topical urea (10%), polidocanol,

pramoxine, and menthol are considered safe during pregnancy. Phototherapy (UVB) is a safe additional tool, particularly

for severe cases in early pregnancy. Secondary bacterial infection may require

systemic antibiotics (e.g. penicillins, cephalosporins). Severe cases may require a short course of systemic

corticosteroids.

Treatment ladder

First line

·

Topical emollients

·

Topical corticosteroids

·

Oral antihistamines: loratadine and

cetirizine

Second line

·

Narrow‐band UVB

phototherapy

Third line

·

Prednisolone

Dermatoses

Associated with Fetal Risk in Pregnancy

At a Glance

|

·

Pemphigoid gestationis is an immunologically

mediated, intensely pruritic, vesiculobullous eruption of mid- to late

pregnancy that is associated with fetal risk. ·

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy represents

a reversible form of cholestasis in late pregnancy associated with

biochemical abnormalities and a risk of fetal complications, but invariably

lacking primary cutaneous lesions. Symptoms remit within 2–4 weeks of

delivery, but recurrences in subsequent pregnancies are common. ·

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare, acute,

pustular eruption often accompanied by fever, leukocytosis, and an elevated

erythrocyte sedimentation rate. This is generally regarded as a variant of

psoriasis. |

Pemphigoid

gestationis (PG)

Salient features

·

Rare

pruritic vesiculobullous eruption that develops during

late pregnancy or the immediate postpartum period

·

Linear

C3 deposition along the basement membrane zone (BMZ) by direct IF

·

IgG1

autoantibodies directed against a transmembrane hemidesmosomal protein (BP180;

collagen XVII)

·

Increased

risk of prematurity and small-for-gestational age neonates; the risk correlates

with disease severity

·

Commonly

recurs in subsequent pregnancies

Introduction

Pemphigoid

gestationis (PG) is a rare, self-limited and intensely pruritic, autoimmune, bullous disorder that presents mainly in mid-to late

pregnancy or the immediate postpartum period. It is the most clearly characterized

dermatosis of pregnancy and the only one that may also affect the skin of the

newborn.

Epidemiology

The incidence of

pemphigoid gestationis has been estimated at 1: 2000 to 1: 50 000 pregnancies, depending on the prevalence of HLA-DR3 and -DR4 in different

populations. While occurring primarily during pregnancy and the immediate

postpartum period, pemphigoid gestationis has rarely developed in association

with trophoblastic tumors (hydatidiform mole, choriocarcinoma), implicating a

role for paternally derived tissues in the pathogenesis of this condition. Patients

with a history of pemphigoid gestationis appear to be at increased risk for the

development of Graves’s disease.

Pathophysiology

Historically, pemphigoid gestationis was

thought to be caused by an anti-BMZ “serum factor” (the “herpes gestationis

[HG] factor”) that induces C3 deposition along the dermal–epidermal junction.

This factor is now known to be complement-fixing autoantibodies of the IgG1

subclass directed against a 180 kDa transmembrane hemidesmosomal protein

(BPAG2; collagen XVII). As in patients with bullous pemphigoid (BP), it is the

non-collagenous (NC) segment closest to the plasma membrane of the basal

keratinocyte (NC16A) that constitutes the immunodominant region of BP180.

Circulating antibodies are almost exclusively directed against this domain, as

demonstrated by ELISA and immunoblot studies of maternal or neonatal sera.

Of interest, the

primary site of autoimmunity seems not to be the skin, but the placenta, as

antibodies bind not only to the basement membrane zone of the epidermis, but

also to the amniotic basement membrane (a structure

derived from fetal ectoderm and antigenically similar to skin). So attention has focused on immunogenetics and

potential cross-reactivity between placental tissue and skin. Women with

pemphigoid gestationis also have increased expression of MHC class II antigens

(DR, DP, DQ) within the villous stroma of their chorionic villi. It has

therefore been proposed that pemphigoid gestationis is a disease, initiated by

the aberrant expression of MHC class II antigens (of paternal haplotype), that

serves to initiate an allogeneic response to placental BMZ, which then

cross-reacts with skin.

Clinical

features

Pemphigoid gestationis presents with

intense pruritus that occasionally may precede skin lesions. There is

an abrupt onset of cutaneous lesions on the trunk, in particular the abdomen

and often within or immediately adjacent to the umbilicus. Rapid progression to

a generalized pemphigoid-like eruption then occurs, with pruritic urticarial

papules and plaques, followed by clustered (herpetiform) vesicles or tense

bullae on an erythematous base. The eruption may involve the entire body,

sparing only the mucous membranes. In

the pre‐bullous stage, differentiation between PG and PEP is almost

impossible, both clinically and histopathologically.

Disease

course and fetal prognosis

The

natural course of PG is characterized by exacerbations and remissions during

pregnancy, with spontaneous

improvement during late gestation is common. This is followed, however, by a

flare at the time of delivery in 75% of patients. Such flares may be dramatic,

with an explosive onset of blistering within hours. After delivery, the lesions usually resolve within weeks to

months.

Flares and/or recurrences in association with menstruation are common, and in

25–50% of patients, they may also be induced by oral contraceptives. Pemphigoid

gestationis may not develop during the patient’s first pregnancy, but,

once established, it is quite likely to recur in subsequent pregnancies,

usually with an earlier onset and more severe course. “Skipped” pregnancies

have been observed in 5–8% of women.

Approximately

10% of newborns develop mild skin involvement (neonatal

PG) due

to passive transfer of maternal antibodies and this resolves spontaneously

within days to weeks. There seems to be an increased risk of prematurity and

small-for-gestational age neonates, presumably due to chronic placental

insufficiency; the risk of these fetal complications correlates with maternal disease

severity (i.e. occurrence of blistering and early onset) and not with the use

of systemic corticosteroids. Therefore, women with PG should be followed

closely by their obstetrician. If the mother has received long term high doses

of prednisolone, the infant should be evaluated for evidence of adrenal

insufficiency.

Investigations

Patients in whom PG is suspected

usually require a biopsy for histopathology and DIF. Histopathologic findings

from lesional skin depend on the stage and severity of the disease. The pre‐bullous

stage is characterized by edema of the upper and middle dermis accompanied by a

predominantly perivascular inflammatory infiltrate, composed of lymphocytes,

histiocytes and a variable number of eosinophils. Histopathology of the bullous

stage demonstrates subepidermal blistering that, ultrastructurally, is located

at the lamina lucida of the dermo‐epidermal

junction.

Direct

immunofluorescence of perilesional skin, the gold standard in the diagnosis of

PG, shows linear C3 deposition along the dermo‐epidermal

junction in 100% of cases and additional IgG deposition in 30% of cases. Circulating

IgG antibodies in the patient's serum may be detected by indirect immunofluorescence

in 30–100% of cases, binding to the roof of the artificial split on salt‐split

skin. Determination

of antibody titers via BP180-NC16A ELISA may be helpful in following disease

activity and monitoring therapy.

Treatment

The

primary goal in treating this self-limited disease is to relieve pruritus and

suppress blister formation. In mild cases, the use of potent topical

corticosteroids combined with emollients and systemic antihistamines may be

adequate. However, systemic corticosteroids remain the cornerstone of therapy.

Most patients respond to 0.5 mg/kg of prednisolone daily; the dose is tapered

as soon as blister formation is suppressed. The common flare associated with

delivery usually requires a temporary increase in dosage. Persistent disease after delivery is uncommon and is treated like BP. Cases unresponsive to systemic corticosteroid treatment or

in cases where prolonged treatment with corticosteroid is contraindicated may

benefit from third line treatments including intravenous immunoglobulins and plasmapheresis

during pregnancy.

Treatment ladder

First line

·

Topical emollients: aqueous cream +

1–2% menthol

·

Potent topical steroids

·

Oral antihistamines: loratadine and

cetirizine

Second line

·

Prednisolone

Third line

·

Plasma exchange

·

Intravenous immunoglobulins

Cholestasis of pregnancy, intrahepatic

Salient features

·

Pruritus without primary skin lesions with an onset during the

third trimester

·

Secondary changes correlate with disease duration and vary from

subtle excoriations to severe prurigo nodularis

·

Elevated total serum bile acid levels are diagnostic; histology

is nonspecific and IF is negative

·

Increased risk of prematurity, intrapartum fetal distress, and

stillbirths

·

Recurs in 45–70% of subsequent pregnancies

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a rare,

reversible form of hormonally triggered cholestasis that typically develops in

genetically predisposed individuals in late pregnancy, when serum

concentrations of estrogen reach their peak.

Although maternal

prognosis is usually good (a small minority may develop steatorrhea and vitamin

K deficiency), fetal risk is significant. As a result, ICP is the most important

pruritic gestational condition to consider and promptly diagnose and treat in

order to prevent fetal impairment.

Epidemiology

It occurs in 1 in

1500 pregnancies and a positive family history is seen in 50% of affected

individuals. A higher incidence of ICP is also seen in multiple-gestation

pregnancies, which may be related to higher hormonal levels (e.g. estrogen) in

these patients.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The key

element is reduced excretion of bile acids, which leads to increased serum

levels. This not only provokes severe pruritus in the mother, but also may have

deleterious effects on the fetus. Toxic bile acids crossing the placenta can

lead to acute fetal anoxia due to abnormal uterine contractility and

vasoconstriction of chorionic veins as well as impaired fetal cardiomyocyte

function. One predisposing factor is mutations in genes (e.g. ABCB4) that encode bile transporter proteins. While

mild dysfunction of these canalicular transporters may not lead to clinical

symptoms in non-pregnant individuals, when the transporters’ capacity to

secrete substrates is exceeded (as occurs in the setting of high levels of sex

hormones during pregnancy), signs and symptoms of cholestasis can develop.

Other contributing factors are the cholestatic effect of estrogen and

progesterone metabolites, which peak late during pregnancy and hepatitis C

viral infection.

Although the

precise pathogenesis remains unclear, the interplay of hormonal, genetic,

environmental, and alimentary factors is thought to induce a biochemical

cholestasis in susceptible individuals. A prominent role for hormonal

alterations is suggested by the following observations: (1) ICP is a disease of

late pregnancy (corresponding to the period of highest placental hormone

levels); (2) ICP spontaneously remits at delivery when hormone concentrations

normalize; (3) twin and triplet pregnancies, characterized by greater rises in

hormone concentrations, have been linked to ICP; and, (4) ICP recurs during

subsequent pregnancies in an estimated 45%–70% of patients.

Geographic

variation and familial clustering indicate a genetic predisposition. ICP appears

to be a polygenetic condition. There are reports of higher incidence rates

during the winter months, and furthermore, dietary factors such as selenium

deficiency and increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut“) have been

suggested as possible triggers, all point toward etiologic roles for

environmental and alimentary factors.

Clinical

features

ICP

is the only pregnancy dermatosis that presents without primary skin lesions. Patients typically

present during their last trimester with a sudden onset of intense, generalized

pruritus that often starts on the palms and soles. Pruritus begins during the first

and second trimester in 10% and 25% of cases, respectively. No primary skin

lesions are seen, and secondary changes due to scratching vary from subtle

excoriations early on to pronounced prurigo nodularis in those with pruritus of

longer duration. The extensor surfaces of the extremities, buttocks, and

abdomen are usually most severely affected. Initially, patients may complain of nocturnal

pruritus only, and symptoms generally are more severe at night throughout the

course of illness.

Constitutional

symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, vomiting, or anorexia may accompany the pruritus.

Progression to clinical jaundice, dark urine, or lightly colored stools occurs

in approximately one in five patients. Jaundice is usually a complication in those

with the most severe and prolonged episodes of ICP. In such patients,

concomitant extrahepatic cholestasis may be associated with steatorrhea and subsequent

vitamin K deficiency (malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins including vitamin

K) leading to an increased risk of intra- and postpartum hemorrhage.

Disease

course and fetal prognosis

Pruritus typically

persists until delivery. The prognosis for the mother is

generally good as pruritus and associated biochemical abnormalities typically disappear spontaneously within 2 to 4 weeks after delivery. A protracted course is very unusual and

should prompt one to exclude other liver diseases, especially primary biliary

cirrhosis. Recurrences

during subsequent pregnancies occur in an estimated 45%–70% of patients. Some

women experience recurrent ICP after exposure to oral contraceptives or to

contraceptive aids, such as synthetic estrogens and progestational agents. In cases of jaundice and vitamin K deficiency, there is an

increased risk for intra‐ and postpartum hemorrhage in both the mother and child. Additionally,

affected women have a tendency toward the later development of cholelithiasis

or gallbladder disease.

ICP is

associated with significant fetal risk, in particular an increase in premature

births (20–60%), intrapartum fetal distress (20–30%; e.g. meconium staining of

amniotic fluid, abnormal fetal heart rate), and stillbirth (1–2%).

Fetal risk correlates with the elevation in serum bile acid levels, especially

when levels exceed 40 µmol/l. Such fetal

complications may be reduced with treatment and induction of labor after fetal

pulmonary maturation has been documented. Thus, prompt diagnosis and

treatment is essential, as is close obstetric surveillance.

Laboratory Studies

Histologic

findings in the skin and the liver are nonspecific and direct IF of

perilesional skin is negative. Elevation in serum

bile acid levels is the

single most sensitive indicator of ICP. The diagnosis is confirmed by an increase in

total serum bile acid levels (>11 µmol/l in a

pregnant woman that is

consistent with ICP. In healthy pregnant women, total bile acids (TBAs) are

slightly elevated above baseline and levels as high as 11.0 μM are accepted as

normal in late pregnancy. Clearly defined biochemical indices of ICP have not

yet been established. However, Brites et al identified the following common

features of ICP: (1) serum TBA concentrations greater than 11.0 μM (normal

range, 4.6–8.7 μM); (2) cholic acid–chenodeoxycholic acid ratio greater than

1.5 (normal range, 0.7–1.5) or cholic acid proportion of TBAs greater than 42%;

(3) glycine conjugates–taurine conjugates of bile acids ratio less than 1.0

(normal range, 0.9–2.0) or glycocholic acid concentration greater than 2.0 μM

(normal range, 0.6–1.5 μM). Degree of pruritus and disease severity generally

correlates with bile acid concentrations.

Mild perturbations in liver

function tests, including elevated transaminases, alkaline phosphatase,

5′-nucleotidase, cholesterol, triglycerides, phospholipids, and lipoprotein X

are commonly found. Among these parameters, alanine transaminase is

particularly sensitive, as an elevation in this enzyme is not a feature of

healthy pregnancies,

is usually elevated in those with ICP, but may be normal in 30% of patients. Gama glutamyl transferase, which

is generally low in late gestation, is typically normal or slightly elevated in

ICP. During

pregnancy, alkaline phosphatase levels typically increase (placental origin)

even in the absence of ICP. In

women with jaundice, conjugated (direct) bilirubin levels are increased and the

prothrombin time may be prolonged. Albumin may be slightly reduced, whereas α2-globulins

and β-globulins are appreciably elevated.

Hepatic

ultrasonography generally is normal.

Differential Diagnosis

Distinction

from other causes of pruritus in the pregnant woman can be challenging. The

presence of primary lesions points away from a diagnosis of ICP, which lacks

primary lesions. In

the absence of primary lesions, the clinical differential diagnosis includes

other causes of primary pruritus, including those that lead to cholestatic

pruritus. Viral hepatitis is a common disorder and should be excluded by

appropriate serologies. Of note, a history of hepatitis C viral infection is

considered a risk factor for the development of ICP, and in one study, 20% of

the women who were HCV RNA-positive developed ICP.

Other causes of liver derangement

and jaundice, such as non viral hepatitis, medications, hepatobiliary

obstruction, and other intrahepatic diseases (i.e., primary biliary cirrhosis)

must be ruled out. Finally, it must be remembered that hyperthyroidism,

allergic reactions, polycythemia vera, lymphoma, pediculosis, and scabies may

each manifest as generalized pruritus in pregnant as in nonpregnant women.

Treatment

Since

fetal prognosis correlates with disease severity, the therapeutic goal is

reduction of serum bile acid levels. This allows prolongation of the pregnancy

and lessens both fetal risk and maternal symptoms. An interdisciplinary approach

characterized by intense fetal surveillance is essential to the management of

ICP.

In mild cases, adequate relief of

maternal symptoms can be achieved with bland emollients and topical

antipruritic agents.

To date, the only

successful agent has been oral ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) as it reduces both maternal itch and fetal risk.

It

is a naturally occurring, hydrophilic, non-toxic bile acid that has been used

for a variety of cholestatic liver diseases. Although the exact mechanism of

action in ICP is still not fully understood, there is evidence that UDCA

corrects the maternal serum bile acid profile, decreases the passage of

maternal bile acids to the fetoplacental unit, and improves the function of the

bile acid transport system across the trophoblast. UDCA is safe for mother and

fetus, with its only side effect being mild diarrhea. Use of UDCA for ICP is

off-label as it is only approved for primary biliary cirrhosis. The recommended

oral dose is 15 mg/kg daily or, independent of body weight, 1 g daily, taken as

a single dose or divided into two to three doses. It should be started as early

as possible and administered until delivery. At this dose, UDCA is well tolerated and highly effective in

controlling the clinical and liver function abnormalities that define ICP.

In

jaundiced patients, the prothrombin time should be monitored, and intramuscular

vitamin K administered as necessary. In

addition to UDCA treatment, weekly fetal heart rate cardiotocographic

monitoring from 34 weeks' gestation onwards until childbirth. Early delivery (as

soon as fetal lung maturity is achieved at 36 to 37 weeks) is recommended by several authors.

Therapeutic ladder

First line

·

Topical emollients: aqueous cream +

1–2% menthol

·

Oral antihistamines: loratadine and

cetirizine

·

Oral UDCA 15 mg/kg/day

Second line

·

S‐adenosyl‐l‐methionine

·

Dexamethasone

·

Cholestyramine

Other recommendations

·

Weekly fetal cardiotocography to

monitor fetal heart rate and detect early signs of fetal distress

·

Maternal vitamin K replacement (if

jaundice is present)

·

Early delivery (36–37 weeks)

·

Dexamethasone may be needed for

fetal lung maturity

Pustular Psoriasis of Pregnancy (Impetigo Herpetiformis)

Introduction

Pustular psoriasis

of pregnancy is generally regarded as a variant of pustular psoriasis

attributable to hormonal alterations during pregnancy; however, some authors

maintain that it is a distinct clinical entity.

Von Hebra first

used the designation impetigo herpetiformis in 1872 to describe an acute

pustular eruption with usual onset during the third trimester of pregnancy.

Clinical Features

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy

is characterized by an acute eruption occurring as early as the first, but

generally during the third, trimester of an otherwise uneventful pregnancy. The

condition manifests as erythematous patches whose margins are studded with subcorneal

pustules. The eruption typically originates in flexural areas but spreads

centrifugally and sometimes generalizes. Subungual lesions may result in

onycholysis. Rarely, mucous membrane involvement may lead to painful erosions.

The face, palms, and soles are commonly spared. The rash may be pruritic or

painful.

Onset of the eruption is

accompanied by such constitutional symptoms as fever, chills, malaise,

diarrhea, nausea, and arthralgias. Rarely, tetany, delirium, and convulsions

occur if hypocalcemia is severe.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Although generally regarded as a

form of pustular psoriasis, absence of a positive family history, abrupt

resolution of symptoms at delivery, and a tendency to only recur during

subsequent pregnancies distinguish this entity from generalized pustular

psoriasis. Moreover, factors known to trigger pustular psoriatic flares, such

as infection, exposure to culprit drugs, or abrupt discontinuation of systemic

corticosteroids are lacking in virtually all patients with pustular psoriasis

of pregnancy.

Diagnosis

Although the clinical picture is typical, a biopsy is helpful to confirm the diagnosis. Initial laboratory evaluation should include complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel with particular attention to calcium level.

Histopathologic examination

reveals classic features of pustular psoriasis.

The most common laboratory

derangements include leukocytosis, neutrophilia, an elevated erythrocyte

sedimentation rate, hypoferric anemia, and hypoalbuminemia. Less commonly,

calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D levels are decreased. Serum parathormone

levels are rarely decreased. Cultures of pustule contents and peripheral blood

are negative unless secondarily infected.

Clinical course and prognosis

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy

classically presents during the last trimester, but there are reports of cases

occurring as early as the first trimester, during the puerperium, in

nonpregnant women taking oral contraceptives, and in postmenopausal women.

Symptoms are invariably progressive throughout pregnancy. A cardinal feature of

this disorder is the rapid resolution of symptoms after delivery. Recurrences

in subsequent pregnancies are common and characteristically are more severe

with onset earlier in gestation.

More widespread disease generally

portends a worse prognosis.

Complications

Life-threatening maternal

complications are infrequent today, but may result from profound hypocalcemia and bacterial sepsis. The most feared complications are placental insufficiency

and consequent stillbirth or neonatal death. For these reasons, early induction

of labor is often contemplated.

Treatment

Resolution after delivery is the

norm. However, given its consistently progressive course, treatment is

indicated to reduce the risk of fetal and maternal complications during

pregnancy. Topical treatments include wet dressings and topical corticosteroids,

but are rarely effective as monotherapy. Narrowband UVB combined with topical

steroids has been reported to be successful in rare cases as well.

Systemic corticosteroids were historically

the mainstay of therapy. Now cyclosporine and infliximab are deemed first line therapy. Cyclosporine has been successfully used at doses between 5 mg/kg

and 10 mg/kg daily. Infliximab, a TNF-α blocking agent has been successfully used

without adverse effect on the fetus, but with the caveat that live vaccines

should be delayed in newborns of mothers treated with infliximab. Although careful consideration of the benefits

and risks of TNF-blockade during pregnancy must be considered, these agents (including

etanercept and adalimumab) are Class B and may have a role in the management

of cases refractory to other therapies.

In all, cases, fluid status and

electrolytes should be monitored with rapid correction of imbalances. Fetal

monitoring is essential as decelerations in fetal heart rate may be the

earliest sign of fetal hypoxemia. Maternal cardiac and renal functions may be

compromised with disease progression and therefore should be monitored as well.

Induction of labor is an option when symptoms do not remit despite supportive

and pharmacologic therapy. The therapeutic armamentarium available after

pregnancy termination or after delivery in a non-nursing mother can be extended

to include oral psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA), oral retinoids, and methotrexate.

|

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR CORTICOSTEROID AND

ANTIHISTAMINE USE DURING PREGNANCY |

|

|

Corticosteroids |

|

|

Topical |

Recent

large, population-based studies and a Cochrane review have not shown an increased risk of malformations,

including oral cleft palate, or preterm delivery Because

fetal growth restriction has been reported with extensive use of potent

corticosteroids (CS), particularly >300 g during the pregnancy, mild to

moderate CS are recommended over potent CS If

potent CS are required, the treatment period should be limited in duration Can

add to risk of developing striae |

|

Systemic |

Prednisolone

is the systemic corticosteroid of choice for dermatologic indications as it

is largely inactivated in the placenta (mother: fetus = 10: 1). The usual initial dose is 0.5–2 mg/kg/day depending

on the nature and severity of the disease. In treating pregnancy dermatoses,

corticosteroids are usually used only as a short‐term

therapy (<4 weeks) so that side effects are minimized. During

the first trimester, particularly between weeks 8 and 11, there is a possible

(debated) slightly increased risk of cleft lip/cleft palate, especially if

high doses prescribed (should not exceed

10–15 mg/day) and for >10 days; during this

same period, a longer duration of therapy appears safe if dosages are

<10–15 mg daily If

use is long-term and extends late into gestation, fetal growth should be

monitored and the risk of adrenal insufficiency in the newborn should be

addressed |

|

Antihistamines |

|

|

Systemic |

During

the first trimester, the classic sedating agents (e.g. chlorpheniramine,

diphenhydramine, clemastine, dimethindene) are preferred because of the

preponderance of safety data If

a non-sedating agent is requested, loratadine is the first choice and cetirizine

the second choice; both are considered safe throughout pregnancy, especially in the second and third trimester. |