Genital Chlamydia infection

Introduction

Genital

Chlamydia infection is one of the most commonly reported STIs globally. Vertical transmission during childbirth can also occur. It causes inflammation of the genital and rectal mucous

membranes as well as the conjunctiva, but is often asymptomatic. The causative

organism, Chlamydia trachomatis, is an exclusively human, obligate,

intracellular bacterial pathogen with a complex life cycle.

Chlamydia

trachomatis serovars A–C are responsible for

ocular trachoma, which is a major cause of blindness worldwide. Genital Chlamydia

D–K strain infections are considered the world's most common sexually

transmitted bacterial pathogens. Chlamydia trachomatis serovars L1–L3

cause lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV).

Chlamydia causes a number of clinical syndromes including urethritis,

cervicitis, epididymo‐orchitis,

pelvic inflammatory syndrome, seronegative reactive arthritis and ophthalmia neonatorum.

Epidemiology

Incidence

and prevalence

In 2008, the WHO reported a global

incidence of genital chlamydia and gonorrhoea with >100 million cases of

each. However, genital chlamydia is considered to be at least three times more

prevalent than gonorrhoea.

Age

Age is the most significant risk

factor for chlamydia, with the highest rates being found in those under 25

years old and a decreasing prevalence with increasing age.

Sex

Chlamydial

infection in women is 2.5 times more than men.

Associated

diseases

Individuals

diagnosed with an STI are at risk of other coexistent STIs, therefore a sexual

health assessment is warranted.

Predisposing

factors

The main predisposing factor for Chlamydia

infection appears to be an age of less than 25 years. Cervical ectopy, where

there is visible columnar epithelium on the ectocervix, is more common in

younger women and the prevalence of chlamydia is greater in women with ectopy

than without.

Pathology

Sub-acute and chronic asymptomatic

infection is common and the infection can persist for many months or years if

untreated. The frequent absence of symptoms in the acute phase facilitates

spread.

The clinical manifestations of Chlamydia

infection are probably a direct result of tissue damage as well as host immune

response, resulting in scarring of the affected mucous membranes.

Causative

organisms

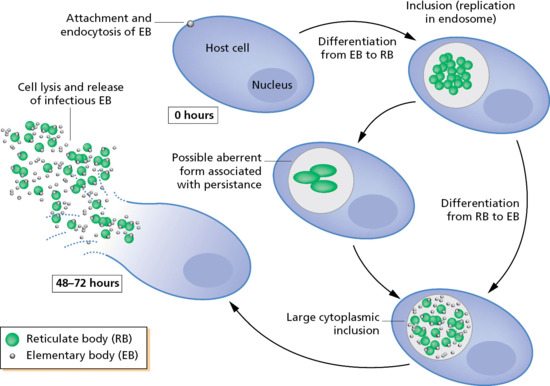

Chlamydiae

are obligate intracellular parasites and exhibit a unique, two‐stage developmental cycle with two

forms:

·

An extracellular, infectious

elementary body (EB).

·

An intracellular, replicative

reticulate body (RB).

This cycle begins when infectious,

metabolically inert EBs attaches to and stimulate uptake by the host cell. The

internalized EB remains within a host‐derived vacuole, termed an inclusion, and differentiate into

a larger, metabolically active RB. The RB multiplies by binary fission, and

after 8–12 rounds of multiplication, the RBs differentiate to EBs asynchronously.

At 48–72 h post‐infection,

EB progeny are released from the host cell to initiate another cycle.

C.

trachomatis strains A–K primarily infect

squamocolumnar epithelial cells.

Clinical

features

Asymptomatic

infection occurs in up to 90% of women and more than 50% of men.

In men, the most common manifestation of disease is anterior

urethritis, characterized by a mucopurulent urethral discharge and dysuria, with an onset 1–3 weeks after

intercourse with an infected partner. Note that the discharge due

to Chlamydia is classically less purulent, less profuse, and less spontaneous

when compared to urethral gonorrhea. Rectal infection may result in proctitis

in men practising receptive anal

intercourse which may be asymptomatic, but some will have symptoms

resembling those seen with gonococcal proctitis. It is important to exclude LGV if rectal symptoms are

present.

In

women, the columnar epithelium of the endocervix is commonly affected. Common

symptoms include inter menstrual or post coital bleeding and vague but persistent

lower abdominal pain, vaginal discharge and dysuria. Typically, in such patients there are signs of mucopurulent

cervicitis and/or contact bleeding.

Extragenital

infections also occur. Pharyngeal infections are usually asymptomatic.

Infection of the eye causes acute follicular conjunctivitis which is usually,

but not always, associated with genital infection. Acute follicular conjunctivitis

is usually associated with Chlamydia whereas chronic conjunctivitis may be seen

in trachoma or lymphogranuloma venereum. Neonates may develop conjunctivitis and

pneumonia after being infected from passage through the birth canal of an

infected mother. Chlamydia in pregnancy may be

associated with premature labor and preterm birth.

Complications and co‐morbidities

Complications mostly occur from

ascending infections and possibly from dissemination, and are also associated

with pregnancy and the neonatal period.

Ascending infection in men causes

epididymo‐orchitis.

Epididymo‐orchitis in

those less than 35 years old is most likely to be caused by a sexually

transmitted organism such as C. trachomatis. Thus, aside from urethral discharge, men

may also present with unilateral scrotal pain and swelling. In those over 35 years old urological pathogens such as Escherichia

coli, Klebsiella sp. or enterococci are more likely.

Chlamydia should be considered as a possible

cause for a Bartholin abscess, with or without concurrent gonococcal infection.

In the absence of treatment, 10–40% of women infected with Chlamydia

will develop PID, with ascending infection to the uterus and

fallopian tubes. Symptoms may include fever, lower abdominal pain, back pain,

vomiting, vaginal bleeding, dyspareunia, and adnexal or cervical motion

tenderness on physical examination. Sequelae of untreated infection include

tubo-ovarian abscesses, ectopic pregnancies, chronic pelvic pain, and

infertility due to chronic inflammation with resultant scarring. The risk of developing PID increases with

each recurrence of C.

trachomatis infection, as does the risk of reproductive

sequelae. Five to ten percent of women with chlamydial PID may develop

perihepatitis. Fitz‐Hugh–Curtis

syndrome presents as upper‐right‐sided abdominal pain and fibrinous

‘violin‐string’ adhesions of the liver capsule as a consequence of

perihepatitis.

Chlamydia

is strongly associated with reactive arthritis and is termed sexually acquired

reactive arthritis (SARA). Reactive arthritis can occur up to 1 month after symptoms

of nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) due to chlamydia. Reactive arthritis can be defined as a sterile inflammatory

arthritis following bacterial infection elsewhere. Individuals with the

haplotype HLA-B27 are at increased risk of developing the reactive arthritis

syndrome. SARA occurs in 0.8–4% of those

infected with Chlamydia. It is a seronegative, asymmetrical,

spondyloarthropathy with or without extra‐articular features that include the following:

·

Mucocutaneous manifestations

including circinate balanitis, erosions affecting the buccal and rectal mucosa

and keratoderma blenorrhagica.

·

Iritis and conjunctivitis.

Prognosis and Clinical

Course

Early treatment with

appropriate antibiotic therapy results in excellent prognosis and reduces the

risk of long-term complications, such as infertility from PID. It is important

to complete an appropriate course of antibiotic.

Laboratory Tests

Traditionally, chlamydial infection was diagnosed by

tissue culture with specimens obtained from the endocervix in women, urethra in

men, and rectum, or conjunctivae, as indicated. More rapid and sensitive tests

have replaced culture in recent years. A direct fluorescent antibody test,

which is highly specific, can be performed on endocervical and penile urethral

specimens with rapid results. Less invasive tests involving nucleic acid

hybridization and nucleic acid amplification, such as PCR, is more commonly

being used to detect even small amounts of chlamydial DNA in urethral, vaginal,

endocervical swabs and in first voided urine samples. It should be noted that

the nucleic acid amplification and hybridization tests are less accurate for

chlamydial detection from rectal and oropharyngeal sites than from genital

sites.

First‐void urine is the sample of choice in men, and in females a

self‐taken vaginal

swab or an endocervical swab are acceptable. In MSM and commercial sex workers,

pharyngeal and rectal testing may also be indicated and NAATs are the only

recommended test. Conjunctival sampling may also be clinically indicated in

some situations.

There

is also some debate about exactly who should receive chalmydial testing, aside

from those whose symptoms suggest that diagnosis. The CDC recommends annual

screening of all sexually active women under the age of 25 and for older women

with risk factors (e.g., those who have a new sex partner or multiple sex partners).

Treatment

Treatment is indicated if chlamydia

is diagnosed or if there is a history of contact with a person known to be

infected. Patients with chlamydia should always be fully assessed and screened

for other STIs and HIV. They should be asked to abstain from sexual contact for

7 days after they and their partners have received treatment and their symptoms

have resolved.

Resistance in C. trachomatis

has been infrequently reported and single‐dose azithromycin is the treatment of choice. It is not

licensed in pregnancy but is recommended by the WHO.

In

complicated infections, more prolonged courses of treatment are employed and

specialist advice may be required.

Uncomplicated

infection

First line

·

Azithromycin 1 g stat (including in

pregnancy)

Second line

·

Doxycycline 100 mg b.d. for 7 days

Third line

·

Ofloxacin 200.300 mg b.d. for 7 days

·

Amoxicillin 500 mg four times a day

for 7 days (pregnancy only)

Complicated

infection

Chlamydial PID

·

Ceftriaxone 500 mg IM single dose+

oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and metronidazole 400 mg twice daily for 14

days

Or

·

Ofloxacin 400 mg PO twice daily +

metronidazole 400 mg PO twice daily for 14 days (if gonorrhoea is unlikely)

Epididymo‐orchitis

·

Ceftriaxone 500 mg IM single dose+ doxycycline

100 mg PO twice daily for 10.14 days

Or

·

Ofloxacin 200 mg PO twice daily for

14 days (if gonorrhoea is unlikely)

Chlamydia‐associated

reactive arthritis

·

Rest

·

Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs

·

Seek specialist advice