Henoch–schönlein purpura

Salient features

·

Most commonly occurs in children

<10 years of age and in association with a preceding respiratory infection,

but may also be seen in adults

·

Intermittent palpable purpura on

extensor extremities and buttocks

·

IgA-dominant immune deposits in

walls of small blood vessels

·

Arthralgias and arthritis

·

Abdominal pain and/or melena

·

Renal vasculitis often mild but can

be chronic

·

In adults, may be associated with an

underlying malignancy

Introduction

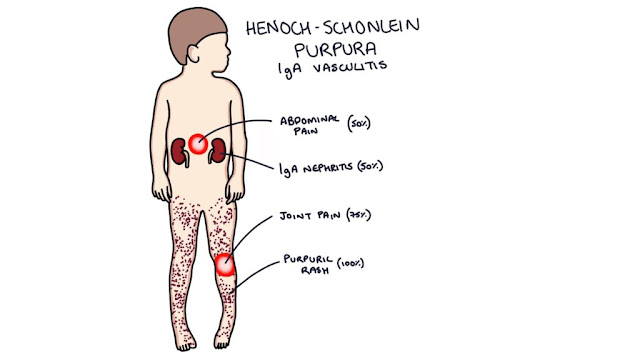

IgA

vasculitis, previously called Henoch–Schönlein purpura (HSP), is an immune

complex vasculitis,

a specific form of CSVV characterized by IgA1‐dominant immune deposits affecting small vessels

(predominantly capillaries, venules or arterioles) that typically

affects children following a recent

upper respiratory tract infection, especially with β-hemolytic streptococcus but

may also occur in adults. Sites of involvement include the skin, synovia,

gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. The classic tetrad consists of palpable purpura (100%), arthritis (75%), abdominal pain (50%) and hematuria (50%).

Epidemiology

HSP is the most common form of vasculitis in children,

with an incidence of 10 to 20 cases per 100 000 children per year. The average

age of onset is 6 years and 90% of cases occur in children <10 years of age.

In adults, the incidence of HSP is 8 to 18 cases per million. HSP has a slight

male predominance in both children and adults.

Pathogenesis

HSP frequently presents 1 to 2 weeks following an upper

respiratory tract infection, especially in children. Streptococcal infections predispose

to IgA vasculitis, and antistreptolysin O titer positivity confers a 10‐fold risk of IgA vasculitis.

The pathogenesis of

IgAV is still largely unknown. The disease is characterized by IgA1-immune

deposits, complement factors and neutrophil

infiltration, which is accompanied with vascular

inflammation. Incidence of IgAV is twice as high during fall and winter,

suggesting an environmental trigger associated to climate. In IgA nephropathy immune complexes containing

galactose-deficient (Gd-)IgA1 are found and thought to play a role in

pathogenesis. Alternatively, it has been proposed that in IgAV IgA1 antibodies

are generated against endothelial cells and

that such IgA complexes can activate neutrophils via

the IgA Fc receptor FcαRI

(CD89), thereby inducing neutrophil migration and activation, which ultimately

causes tissue damage in IgAV.

Certain

genetic polymorphisms may predispose to more severe disease in HSP. For

example, HLA-B35 positivity may predispose to renal disease, while patients who

do not have the ICAM-1 469 K/E variant have less severe gastrointestinal

involvement.

IgA (specifically IgA1) is thought to play a significant

role in the pathogenesis of HSP, as IgA deposits in the walls of postcapillary venules

of the skin and in the renal mesangium, circulating immune complexes containing IgA and increased

serum levels of IgA (in 50% with active disease), have been demonstrated in

patients with HSP. In IgA vasculitis, IgA1 rather than IgA2 is the main IgA

subclass deposited in skin lesions. Lack

of glycosylation of the hinge region of IgA1 may promote the formation of macromolecular

complexes that lodge within the mesangium and activate the alternate complement

pathway.

Clinical features

Most

commonly, IgA vasculitis manifests at the outset with the classic findings of

purpura, arthralgia and abdominal pain. Fever occurs in approximately 20% of adults

and 40% of children. Rarely, gastrointestinal involvement

and arthritis can occur in the absence of skin disease.

The

cutaneous lesions begin as erythematous macules or urticarial papules, which may

evolve within 24 h into palpable purpura with hemorrhage. Hemorrhage vesicles and bullae and necrotic

ulcers may develop. A retiform pattern (raised, geometric, net like

presentation) within lesions is characteristic, but not always present. The

presentation may be identical to CSVV. Although it typically involves the

extensor aspects of the upper and lower limbs (especially the elbows and knees)

and buttocks in a symmetrical fashion, IgA vasculitis may also affect the trunk

and face. Individual

lesions usually regress within 10 to 14 days, with resolution of skin

involvement over a period of several weeks to months.

|

|

Extracutaneous manifestations of HSP are common. Painful

arthritis occurs in up to 75% of patients, most

frequently affecting the knees and ankles. Gastrointestinal involvement

(65% of patients) may precede the purpura and presents with bowel angina

(diffuse abdominal pain that is worse after meals), bowel ischemia, usually

including bloody diarrhea and/or vomiting. Intussusception and bowel

perforation are rare complications.

Renal

involvement with IgA vasculitis is common, occurring in approximately 40–50% of

patients; 25% have gross hematuria and the remainder microscopic hematuria.

Proteinuria occurs in 60% of these, but is uncommon in the absence of

hematuria. Although the appearance of cutaneous lesions often

precedes the development of nephritis, the latter is clinically evident within

3 months. In pediatric patients, risk factors for the development of nephritis

include age >8 years at onset, abdominal pain, and recurrent disease. Less common manifestations of IgA

vasculitis include orchitis (in 10–20% of boys), pancreatitis, neurological

abnormalities, uveitis, and carditis. The lung is also a rare site of involvement,

presenting as hemoptysis and/or pulmonary infiltrates due to diffuse alveolar

hemorrhage. Poor prognostic factors include renal failure at the time

of onset, nephrotic syndrome, and hypertension and decreased factor XIII

activity.

IgA small vessel vasculitis in adults, termed adult HSP,

should be considered separately, as the clinical presentation and prognosis

differ from that in children. For example, necrotic skin lesions are present in

60% of adults while cutaneous necrosis is observed in <5% of children.

Adults with IgA vasculitis are also more likely than children to develop

chronic renal insufficiency (up to 30%), especially if they have purpura above

the waist, fever and an elevated ESR. In addition, when CSVV is due to an

underlying neoplasm, the latter is usually a hematologic malignancy rather than a solid organ malignancy. However, 60–90% of adult patients with

neoplasm-associated IgA vasculitis will have cancer of a solid organ, in

particular lung. Adults are also more likely than children to have diarrhea and

leukocytosis, to require more aggressive therapy, and to have a longer hospital

stay.

Complications

and co‐morbidities

End‐stage renal disease is uncommon but, if it occurs, may need

renal transplantation. Renal transplant survival is over 80% at 5 years.

Disease

course and prognosis

- Abdominal

pain usually settles within a few days.

- About 25% of patients will

relapse

of the disease within 6 months

and typically the relapse is mild and easily treated.

- IgA vasculitis can become

chronic in 5–10% of patients, the cutaneous involvement usually lasting between

6 and 16 weeks.

- Patients

without kidney involvement can expect to fully recover within 4-6 weeks.

- Only 1% of these patients will go on to

develop end stage renal disease.

Investigations

IgA

vasculitis is a clinical diagnosis, with confirmation by direct

immunofluorescence and routine histology.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis of

the small dermal blood vessels is seen. Perivascular

IgA deposits in DIF are characteristic of IgA

vasculitis and can help to distinguish it from other vasculitides including

CSVV. Of note, a small subset of patients has been described that meets

clinical criteria of HSP but lacks IgA deposition on DIF.

Differential diagnosis

Because up to 80% of all adults with CSVV may

demonstrate some vascular IgA deposition and IgA deposition can be seen in

other diseases (e.g. drug hypersensitivity, IgA monoclonal gammopathy,

inflammatory bowel disease, lupus erythematosus, cryoglobulinemia), a

diagnosis of HSP is supported by IgA predominance in

the correct clinical setting. Of the several proposals for diagnostic

criteria, the one developed by the European League against Rheumatism/Pediatric

Rheumatology European Society (EULAR/PReS), may be the most clinically relevant

to the dermatologist. In addition to palpable purpura (a required criterion),

at least one of the following must be present:

|

|

• |

|

|

|

• |

diffuse

abdominal pain that is worse after meals |

|

|

• |

any biopsy demonstrating predominant IgA deposition |

|

|

• |

Renal involvement in the form of hematuria and/or proteinuria. |

Treatment

Because

HSP is generally self-limited and resolves over the course of weeks to months,

treatment is mainly supportive. Dapsone and colchicine may decrease the

duration of cutaneous lesions and frequency of recurrences. Systemic

corticosteroids (prednisolone

1 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks, tapering over a further 2 weeks), are effective in treating the arthritis and abdominal pain

associated with HSP, as well as reducing the gastrointestinal complications and

duration of skin lesions, but do not prevent recurrences of purpura. Referral

to a nephrologist is appropriate for patients with evidence of renal

involvement. In adults, the following factors may predict relapsing disease:

age >30 years, an underlying systemic disorder, persistent purpura >1

month, abdominal pain, hematuria, and absence of IgM on DIF.

Considerable controversy

surrounds the use of corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressive medications for

the treatment of severe renal disease and for preventing renal sequelae in

individuals who have severe renal involvement. Pulsed intravenous methylprednisolone,

cyclosporine A, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil are used

for the treatment of severe renal disease. In sum, the current consensus

appears to be that corticosteroids do not prevent renal disease but could be

used to treat severe nephritis.