Herpes zoster

Salient features

- Herpes

zoster is characterized by unilateral dermatomal pain and rash that

results from reactivation and multiplication of latent VZV that persisted

within neurons following varicella.

- The

erythematous maculopapular and vesicular lesions of herpes zoster are

clustered within a single dermatome, because VZV reaches the skin via the

sensory nerve from the single ganglion in which latent VZV reactivates,

and not by viremia.

- Herpes

zoster is most common in older adults and in immunocompromised

individuals.

- Pain

is an important manifestation of herpes zoster. The most common

debilitating complication is chronic neuropathic pain that persists long

after the rash resolves, a complication known as postherpetic neuralgia

(PHN).

- Antiviral

therapy and analgesics reduce the acute pain of herpes zoster. Lidocaine

patch (5%), high-dose capsaicin patch, gabapentin, pregabalin, opioids,

and tricyclic antidepressants may reduce the pain of PHN.

- A

live attenuated Oka/Merck strain VZV herpes zoster vaccine (ZVL; Zostavax®)

reduces the incidence of herpes zoster by one-half and the incidence of

PHN by two-thirds. An adjuvanted recombinant glycoprotein E subunit herpes

zoster vaccine (RZV; Shingrix®) has substantially greater

efficacy for herpes zoster and PHN, but it requires 2 doses and is more

reactogenic.

Introduction

Zoster

(zoster = a girdle, a reference to its segmental distribution) affect

individuals who have previously had clinical or subclinical varicella or vaccination. Zoster patients are

infectious, both from virus in the lesions and, in some instances, the

nasopharynx. In susceptible contacts of zoster, chickenpox can occur.

Epidemiology

Although the incidence and severity of herpes

zoster increase substantially in middle to late adulthood, it can occur at any

age and is more common in younger persons who had a varicella infection within

the first year of life. Overall, individuals with a history of varicella have a

20% lifetime chance of developing zoster. Incidence of herpes zoster

is determined by factors that influence the host-virus relationship.

One strong risk

factor is older age. The incidence of zoster increases with age and the mean age of zoster is about 60 years.

Another major risk factor is cellular immune dysfunction.

Immunosuppressed patients have a 20–100 times greater risk of herpes zoster

than immunocompetent individuals of the same age. Immunosuppressive conditions

associated with high risk of herpes zoster include HIV infection, bone marrow

transplant, leukemia and lymphoma, use of cancer chemotherapy, and use of

corticosteroids. Herpes zoster is a prominent and early “opportunistic

infection” in persons infected with HIV, in whom it is often the first sign of

immune deficiency. Thus, HIV infection should be considered in individuals who

develop herpes zoster.

Other factors reported to increase the risk of herpes

zoster include female sex, mental and physical

stress, a family history of zoster, use of tofacitinib or proteasome inhibitors

(e.g. bortezomib, carfilzomib), physical trauma in the affected

dermatome and IL-10 gene polymorphisms.

Virus reactivation usually occurs once in a lifetime. Second

episodes of herpes zoster are uncommon in immunocompetent persons, and third

attacks are very rare. Persons suffering more than one episode may be

immunocompromised. Immunocompetent patients suffering multiple episodes of

herpes zoster-like disease are likely to be suffering from recurrent

zosteriform herpes simplex virus infections.

Patients with herpes zoster are less contagious than

patients with varicella. Virus can be isolated from vesicles and pustules in

uncomplicated herpes zoster for up to 7 days after the appearance of the rash,

and for much longer periods in immunocompromised individuals. Fluid from herpes zoster vesicles can transmit VZV to

seronegative individuals, leading to varicella but not herpes zoster. The

transmission rate to susceptible household contacts is ~15% for zoster,

compared to 80–90% for varicella. Patients with uncomplicated dermatomal

zoster appear to spread the infection via aerosols.

There is evidence that

exposure to

persons with varicella has been reported to increase levels of VZV-CMI and can protect seropositive adults from the development of

zoster. With the universal use of varicella vaccination and decrease in

pediatric and adolescent varicella cases, could

reduce this immune boosting effect, so thatolder persons will no longer

have periodic boosts of the anti-VZV immune activity. This could result in an

increase in the incidence of zoster.

Predisposing

factors

An earlier infection with varicella

is essential before zoster can occur. Most commonly, chickenpox occurs in

childhood and zoster in middle to older age.

Herpes zoster appears upon

reactivation of latent VZV, which may occur spontaneously or induced by other

factors. The mechanisms involved in reactivation of latent VZV are unclear, but

reactivation has been associated with immunosuppression; emotional stress;

irradiation of the spinal column; tumor involvement of the cord, dorsal root

ganglion, or adjacent structures; local trauma; surgical manipulation of the

spine; and frontal sinusitis (as a precipitant of ophthalmic zoster). Most

important, though, is the decline in VZV-specific cellular immunity that occurs

with increasing age.

Pathogenesis

Proposed

pathogenesis of herpes zoster with establishment of persistent but latent

varicella–zoster virus in the sensory-nerve ganglia.

During the course of varicella,

VZV passes from lesions in the skin and mucosal surfaces into the contiguous

endings of sensory nerves and is transported centripetally up the sensory

fibers to the sensory ganglia (the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) of the spinal nerves and the sensory ganglia

of the cranial nerves, also known as cranial nerve ganglia). In the ganglia, the

virus establishes a latent infection where it can remain dormant for several

decades before being reactivated in later life to cause HZ (shingles). The VZV genome persists, both in the neurons and in the glial cells. Despite extensive

research, the molecular and immunological mechanisms responsible for latency

and reactivation are incompletely understood. However, VZV-specific cellular

immunity appears to be critical. Reactivation occurs in those ganglia in which VZV has

achieved the highest density - those innervated by the first (ophthalmic) division of

the trigeminal nerve and by spinal sensory ganglia from T1 to L2.

VZV may also reactivate without producing overt disease.

The small quantity of viral antigens released during such contained

reactivations would be expected to stimulate and sustain host immunity to VZV.

Varicella

and herpes zoster (A) During primary VZII infection (varicella or chicken pox),

virus infects sensory ganglia. (B) VZV persists in a latent phase within

ganglia for the life of the individual. (C) With diminished immune function,

VZV reactivates within sensory ganglia, descends sensory nerves, and replicates

in skin.

When

VZV-specific T cellular immunity falls below some critical level, during ageing

or as a result of immunosuppression, reactivated virus can no longer be contained, virus reactivates from ganglionic neurons

and spreads peripherally or centrally to cause disease. The virus continues

to replicate in the affected ganglion and produces a painful ganglionitis. The reactivation of the VZV destroys a

larger part of the ganglion in the neurons and glial cells. This leads to acute

zoster-associated pain. Infectious virions then spreads antidromically

down the sensory nerve, causing neuronal inflammation and necrosis that can

result in severe neuralgia, and is released from the sensory nerve endings in

the skin/mucosa, where it produces

the characteristic cluster of zoster vesicles. Spread of the ganglionic

infection proximally along the posterior nerve root to the meninges and cord

may result in local leptomeningitis, cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, and

segmental myelitis. Infection of motor neurons in the anterior horn and

inflammation of the anterior nerve root account for the local palsies that may

accompany the cutaneous eruption.

Central spread to the brain causes meningoencephalitis, while central spread to

intracranial and extracranial arteries produces vasculopathy and

varicella-zoster virus temporal arteritis, respectively. Viremia also occurs

during herpes zoster.

Pain is a major symptom of herpes zoster. It

often precedes and generally accompanies the rash, and it frequently persists

after the rash has healed—a complication known as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).

Zoster can cause some destruction of

nerve fibers in the middle and lower dermis that may persist for over a year

and characteristically does so in patients with post‐herpetic

neuralgia. The inflammation in the nerve

tissue can last for a very long time, cause scars, and loss of certain glial

cells (neuronophagy) that triggers a deafferentiation of the sensory ganglion,

which, in turn, triggers postherpetic neuralgia.

Fluctuation of varicella–zoster virus cellular immunity with

age

Varicella

is the primary infection during childhood that

results in an immune response, which leads to VZV-specific cell-mediated

immunity. Resolution of the primary infection results in the induction of

memory T cells specific for VZV, but the frequency of these T cells and

consequent cellular immunity declines over time. However, it can be enhanced

during an individual's lifetime by two processes:

·

Exogenous boosting as

a result of being in contact with individuals with varicella (chickenpox)

·

Endogenous boosting

as a result of subclinical reactivation of latent virus residing within the

ganglia

Clinical Manifestation

Herpes

zoster classically occurs unilaterally within the distribution of a cranial or

spinal sensory nerve, often with some overflow into the dermatomes above and

below. Rarely, the eruption may be

bilateral.

The

most commonly affected dermatomes are the second cervical to second lumbar

nerves (C2 to L2) and the fifth and seventh cranial nerves.

The thoracic (53%), cervical

(usually C2,3,4, 20%), trigeminal, including ophthalmic (15%), lumber (13%) and

sacral (2%) dermatomes are most commonly involved at all ages, but the relative

frequency of ophthalmic zoster increases in old age. Possibly because

chickenpox is centripetal (located on the trunk), the thoracic region is

affected in two thirds of herpes zoster cases. Herpes zoster manifests in three distinct clinical

stages: (1) prodrome, (2) Eruptive phase, and (3) PHN.

Prodrome of Herpes Zoster

Pain and paresthesia (tingling, burning) in the involved dermatome often precede the

eruption by 1-5 days and persists for 2–3 weeks

(84% of cases). The

pain may become quite intense, constant or intermittent and it is often

accompanied by fever, headache, malaise and tenderness localized to areas of one or more dorsal roots and hyperesthesia of

the skin in the involved dermatome.

The pain may be sharply localized and unilateral, but may be more diffuse. This pre-eruptive

pain of herpes zoster may lead to serious misdiagnosis and misdirected

interventions. There is a correlation with the pain severity and extent of the skin

lesions. Prodromal pain is minimal in immunocompetent persons under 30 years of

age, but it more severe in persons over the age of 60 years. Instead of or in addition to pain, occasionally pruritus may

be an early feature of shingles. The time between the start of the pain and the

onset of the eruption is much less in trigeminal zoster than in thoracic

disease.

A

few patients experience acute segmental neuralgia without ever developing a

cutaneous eruption—a condition known as zoster sine herpete.

Eruptive

phase

Within

1-5 days of the onset of pain, cutaneous lesions appear. Pain, paresthesia and

hyperesthesia can be present.

The most distinctive feature of herpes

zoster is the localization and distribution of the rash, which is nearly always

unilateral and is generally limited to the area of skin innervated by a single

sensory ganglion. The area supplied by the trigeminal nerve, particularly the

ophthalmic division, and the trunk from T3 to L2 are most frequently affected;

lesions rarely occur distal to the elbows or knees.

Although the individual lesions of herpes zoster and

varicella are indistinguishable, those of herpes zoster tend to evolve more

slowly and usually consist of closely grouped vesicles on an erythematous base,

rather than the more discrete, randomly distributed vesicles of varicella. This

difference reflects intraneural spread of virus to the skin in herpes zoster,

as opposed to viremic spread in varicella.

Classically, HZ is a unilateral, dermatomal eruption,

with skin lesions evolving simultaneously from erythematous macules to papules,

vesicles, pustules, and final crusting. Usually not the entire dermatome is

involved. Herpes zoster lesions begin as closely

grouped red papules, rapidly becoming vesicles on an erythematous,

edematous base within 12–24 hours, which may be umbilicated and then pustular by the third day. There may be

bullae formation also. A dusky purple color may

be observed in older vesicles. These dry and crust in 7–10 days. The

adherent crust generally persists for 2–4 weeks and then heals with scarring. In

some cases vesicles do not form or are so small that they are difficult to see.

The vesicles vary in size, in contrast to the cluster of uniformly sized

vesicles noted in herpes simplex. The lesions develop in a continuous or interrupted band in the area of

one, occasionally two and, rarely, three contiguous dermatomes. It

is not uncommon for there to be scattered lesions outside the dermatome,

usually fewer than 20. In normal individuals, new lesions

continue to appear for up to 1 week. The

striking feature is cut‐off

at the mid line, except that a few lesions may appear just

over the line, reflecting the paths of small nerve branches. Often in children, and occasionally

in adults, the eruption is the first indication of the attack. The

rash is most severe and lasts longest in older people, and is least severe and

of shortest duration in children.

Lesions may develop on the mucous

membranes within the mouth in zoster of the maxillary or mandibular division of

the facial nerve, or in the vagina in zoster in the S2 or S3 dermatome.

Regional

nodes draining the area are often enlarged and tender.

Clinical

variants

TRIGEMINAL NERVE

ZOSTER

The fifth cranial, or trigeminal,

nerve has three divisions: the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular. The

ophthalmic division further divides into three main branches: the frontal,

lacrimal, and nasociliary nerves. Involvement of any branch of the ophthalmic

nerve is called herpes zoster ophthalmicus. It constitutes 10% to 15% of all

zoster cases. Involvement of the ophthalmic branch of the fifth cranial nerve

is five times as common as involvement of the maxillary or mandibular branches.

Ophthalmic

zoster

In herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO),

the ophthalmic division of the fifth cranial nerve is involved. This ophthalmic

branch sends branches to the tentorium and to the third and sixth cranial

nerves, which may explain the meningeal signs and, occasionally, the third and

sixth cranial palsies associated with herpes zoster ophthalmicus. Ipsilateral rash extends from eye level to the

vertex of the skull but does not cross the midline.

Ipsilateral preauricular

and, occasionally, submaxillary nodal involvement is a common prodromal event

in HZO and often is valued equivalently with pain, vesiculation, and erythema

in establishing a diagnosis. Prodromal lymphadenopathy should not be confused

with the later reactive adenopathy caused by secondary infection of vesicles.

Headaches, nausea, and vomiting also are common prodromal symptoms.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus may be

confined to certain branches of the trigeminal nerve. If the external division

of the nasociliary branch is affected, which supplies the nasal tip, dorsum and

root of the nose and the medial canthus as well as the cornea, with vesicles on

the side and tip of the nose (Hutchinson’s sign), the eye is involved 76% of

the time, as compared with 34% when it is not involved. Vesicles on the lid

margin are virtually always associated with ocular involvement. In any case,

the patient with ophthalmic zoster should be seen by an ophthalmologist.

Aggressive

treatment with systemic

antiviral therapy should be started immediately, pending ophthalmologic

evaluation. ~50% of patients have ocular involvement, which can include

conjunctivitis, (epi)scleritis, keratitis, uveitis, acute retinal necrosis, and

optic neuritis. May lead to ocular scarring and visual loss. These

complications are reduced from 50% of patients with herpes zoster ophthalmicus

to 20–30% with effective antiviral therapy.

In the absence of prompt

detection and treatment, eye involvement poses a risk to vision. The presence

of orbital edema is an ophthalmologic emergency, and patients must be referred

immediately for specialized ophthalmic evaluation and treatment. Involvement of

the area below the palpebral fissure alone, without upper eyelid or nasal

involvement, is considered less likely to result in ocular complications, in

that the superior maxillary nerve innervates the lower eyelid.

Unlike the cutaneous

lesions, ocular lesions of zoster and their complications tend to recur,

sometimes as long as 10 years after the zoster episode.

Since (intra) ocular

involvement is common and may not be noted by general inspection,

ophthalmologist advice should be recommended in the event of facial HZ with

ocular involvement, in order to determine the treatment strategy and necessity

for ophthalmologist reassessment. The most accurate method to confirm the

diagnosis of intraocular involvement is to demonstrate the presence of VZV DNA

or intraocular production of anti-VZV antibodies.

Postherpetic complications are

more common in HZO than in other manifestations of zoster. In

particular, PHN is observed in well over 50% of patients with HZO and can be

severe and long-lasting. Scarring also is more common, probably as a result of

severe destructive inflammation.

Involvement

of the other sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve is most likely to yield

periocular involvement but spare the eyeball. Involvement

of the ciliary ganglia may give rise to Argyll–Robertson pupil.

Herpes zoster of maxillary branch of

cranial nerve(CN) V

Involvement of CN V2 is

localized to the ipsilateral cheek, the lower eyelid, the side of the nose, the

upper eyelid, the upper teeth, the mucous membrane of the nose, the

nasopharynx, on one side of the palate, uvula and

tonsillar area, the upper gingiva and buccal sulcus. At

times, only the oral mucous membrane is involved, and there are no cutaneous

manifestations. Herpes zoster of the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve

may begin with toothache during its prodromal stage, followed by its vesicular

eruption. So this preeruptive herpetic pain may result in

unnecessary oral surgery or dental treatment.

Herpes zoster of mandibular branch

of CN V

Areas of CN V3 involvement

include vesicles

appear on one side of the head, the external ear

and external auditory canal, one side of the tongue, the floor of the

mouth, lower labial and buccal mucosa. As when

other branches of CN V are involved, prodromal pain in affected areas can

result in incorrect diagnoses.

Herpes

zoster oticus

The facial nerve, mainly a motor

nerve, has vestigial sensory fibers supplying the external ear (including pinna

and meatus) and the tonsillar fossa and adjacent soft palate. Classical sensory

nerve zoster in these fibers causes pain and vesicles in part or all of that

distribution.

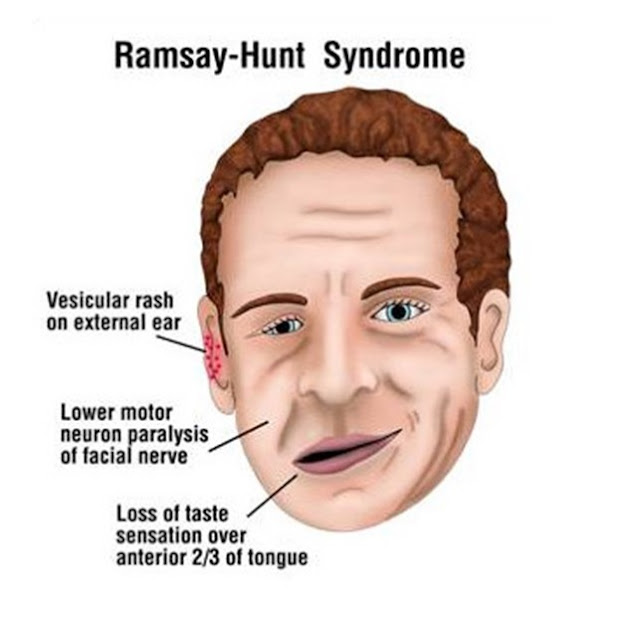

Ramsay

Hunt syndrome results from involvement of the facial and auditory nerves by

VSV. Herpetic inflammation of the geniculate ganglion is felt to be the cause

of this syndrome.

There

is involvement of the sensory portion and motor portion of the seventh cranial

nerve. There may be unilateral loss of taste on the anterior two thirds of the

tongue as well as vesicles on the tympanic membrane, external auditory meatus,

concha, and pinna, tonsillar fossa and adjacent soft

palate.

Involvement of the motor division of the seventh cranial nerve causes

unilateral facial paralysis. If the vestibulocochlear nerve is also affected

due to the close proximity of the geniculate ganglion to the vestibulocochlear

nerve within the bony facial canal: tinnitus, vertigo, otalgia, nausea,

vomiting, nystagmus and deafness.

It is recommended to seek advice of an

otorhinolaryngologist, especially in the case of involvement of the facial or

auditory nerves, in order to determine the treatment strategy and necessity for

otorhinolaryngologist reassessment.

Sacral zoster (S2, S3,

or S4 dermatomes)

A

neurogenic bladder with urinary hesitancy or urinary retention has reportedly

been associated with zoster of the sacral dermatome S2, S3, or S4. Migration of

virus to the adjacent autonomic nerves is responsible for these symptoms.

Herpes zoster sine

herpete

It is defined as the presence of unilateral dermatomal

pain without cutaneous lesions in patients with virologic and/or serologic

evidence of VZV infection. The most accurate method to confirm the diagnosis is

to demonstrate an increase in the blood of anti-VZV IgG and IgM. The

identification of specific serum IgA may be of additional value. In cases of HZ

sine herpete with facial palsy, VZVDNA may be detected in oropharyngeal swabs

2–4 days after the onset of facial palsy using PCR.

Childhood HZ is

quite similar to adult HZ, but ZAP is absent in the majority of cases.

Pain of acute Herpes Zoster

Although the rash is

important, pain is the cardinal problem of acute herpes zoster, especially in

the elderly. Most patients experience dermatomal pain or discomfort during the

acute phase (The first 30 days following rash onset) that ranges from mild to

severe. Patients describe their pain or discomfort as burning, deep aching,

tingling, itching, or stabbing. For some patients, the pain intensity is so

great that words like horrible or excruciating are used to describe the

experience.

Herpes zoster during pregnancy

Herpes zoster during pregnancy,

whether it occurs early or late in the pregnancy, appears to have no

deleterious effects on either the mother or the infant.

Herpes Zoster in the Immunocompromised Host

Except for PHN, most serious complications of herpes

zoster occur in immunocompromised persons. In

immunocompromised patients, both the incidence and severity of zoster are

increased, and it is frequently complicated by generalized varicella

(‘disseminated zoster’). Cutaneous dissemination is defined

as more than 20 vesicles outside the area of primary or adjacent dermatomes producing

a varicella-like eruption and is probably a result of hematogenous spread of

the virus. The dermatomal lesions are sometimes hemorrhagic or gangrenous. The

outlying vesicles or bullae, which are usually not grouped, resemble varicella

and are often umbilicated and may be hemorrhagic. This is seen in malignancy, especially

lymphomas, AIDS and also in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy. If

the rash spreads widely from a small, painless area of herpes zoster, the

initial dermatomal presentation may go unnoticed, and the ensuing disseminated

eruption may be mistaken for varicella. Patients with cutaneous dissemination

also manifest widespread, often fatal, visceral dissemination, particularly to

the lungs, liver, and brain that occurs in 10% of

immunocompromised patients. Anti‐tumour necrosis factor (TNF) ‐α therapy is estimated to increase

the risk of zoster threefold.

In

patients infected with HIV, zoster is 10 times more common than in the normal

population and

may be the earliest clinical sign of the development of AIDS in high-risk

individuals. HIV-infected patients are fairly unique in their tendency to

suffer multiple recurrences of herpes zoster as their HIV infection progresses;

herpes zoster may recur in the same or different dermatomes or in several

contiguous or noncontiguous dermatomes. Herpes zoster in patients with AIDS may

be severe, with cutaneous and visceral dissemination. Patients with AIDS may

also develop chronic verrucous, hyperkeratotic, or ecthymatous cutaneous

lesions caused by acyclovir-resistant VZV.

Unilateral herpes zoster involving

multiple dermatomes

Involvement of more than 1

dermatomal distribution in unilateral zoster is rare and usually is considered

a harbinger of significant compromise of the immune system caused by AIDS,

malignancy, chemotherapy, and other factors. Involvement of 2 dermatomes may be

referred to as zoster duplex, and involvement of 3 or more may be referred to

as zoster multiplex.

Bilateral herpes zoster

On rare occasions, herpes

zoster manifests bilaterally. Bilateral presentations should always raise

concern for disseminated disease (and immunocompromise) or for alternate

diagnosis, specifically for herpes simplex.

In cases of bilateral zoster,

it is not unusual for 1 or 2 adjacent dermatomes to be involved. Unlike

examples of multiple dermatomal involvements in unilateral disease, involvement

in adjacent dermatomes is not typically a sign of underlying disease (eg,

malignancy).

Recurrent herpes zoster

Recurrences of herpes zoster do

occur rarely and are not limited to those who are immunocompromised. The

incidence rate of herpes zoster is 5.1 cases per 1000 person years; its

recurrence rate was calculated at 12 cases per 1000 person years. Risk factors

include old age (51-70 years) and zoster-related pain longer than 30 days. Many

cases of recurrent zoster involve other entities, usually herpes simplex in a

linear distribution.

Complications

and co‐morbidities

Complications of Herpes Zoster

|

Cutaneous |

Visceral |

Neurologic |

|

Bacterial superinfection |

Pneumonitis |

Postherpetic neuralgia |

|

Scarring |

Hepatitis |

Meningoencephalitis |

|

Zoster gangrenosum |

Esophagitis |

Transverse myelitis |

|

Cutaneous dissemination |

Gastritis |

Peripheral nerve palsies |

|

Pericarditis |

Motor |

|

|

Cystitis |

Autonomic |

|

|

Arthritis |

Cranial nerve palsies |

|

|

Sensory loss |

||

|

Deafness |

||

|

Ocular complications |

||

|

Granulomatous angiitis (causing contralateral

hemiparesis) |

The sequelae of herpes zoster include cutaneous, ocular,

neurologic, and visceral complications. Most complications of herpes zoster are

associated with the spread of VZV from the initially involved sensory ganglion,

nerve, or skin, either via the bloodstream or by direct neural extension. The

rash may disseminate after the initial dermatomal eruption has become apparent.

When immunocompetent patients are carefully examined, it is not uncommon to

have at least a few vesicles in areas distant from the involved and immediately

adjacent dermatomes. The disseminated lesions usually appear within a week of

the onset of the segmental eruption and, if few in number, are easily overlooked.

More extensive dissemination occurs in immunocompromised patients.

When the dermatomal rash is

particularly extensive, as it often is in severely immunocompromised patients,

there may be superficial gangrene with delayed healing and subsequent scarring

which is sometimes hypertrophic or keloidal. Secondary bacterial infection may

also delay healing and cause scarring.

Zoster-associated pain and Post‐herpetic neuralgia

Pain is the most troublesome symptom of zoster. 84% of patients

over the age of 50 will have pain preceding the eruption and 89% will have pain

with the eruption. Various terminologies are used to classify the pain. The

simplest approach is to term all pain occurring immediately preceding or after

zoster “zoster associated pain” (ZAP). Zoster-associated pain includes the entire

pain spectrum of HZ with three distinguishable phases: acute pain phase (up to

first 30 days), subacute pain phase (30–90 days after rash healing) and post

herpetic neuralgia (PHN, pain for more than 90 days after the onset of rash). A

prodromal phase as part of acute ZAP, with an onset of pain or dysaesthesia

prior to visible symptoms of HZ, may additionally be distinguished. In the

prodromal phase of HZ, pain can be observed 2–18 days before the appearance of

skin lesions, often leading to a wide array of erroneous diagnoses, according

to the anatomical site of VZV reactivation, including myocardial infarction,

cholecystitis, etc.

PHN is the commonest and

most intractable sequel of zoster, and its incidence increases with

increasing age. It may develop as a continuation of

the pain that accompanies acute zoster, or it may develop after apparent

resolution of the initial zoster reactivation and generally defined as persistence or recurrence of pain more

than a month after the onset of zoster, but better considered after 3 months. The

pain may last for months to years.

Age is the most significant risk factor for PHN. The

tendency to have persistent pain is age dependent, occurring for longer than 1

month in only 2% of persons under 40 years of age. 50% of persons over 60 years

of age and 75% of those over 70 years of age continue to have pain beyond 1

month. Although the natural history is for gradual improvement in persons over

70 years, 25% have some pain at 3 months and 10% have pain at 1 year. Severe

pain lasting longer than 1 year is uncommon, but 8% of persons over 60 have

mild pain and 2% still have moderate pain at 1 year. Individuals affected by

ophthalmic HZ with keratitis or intraocular inflammation are found to be at

higher risk for PHN. A scoring system for the calculation of the individual PHN

risk, including the following risk factors has been proposed: female gender,

age >50 years, the presence of prolonged

prodromal

pain, severe pain during the acute phase of herpes zoster, prolonged

with greater rash severity with >50 lesions, more extensive sensory

abnormalities in the affected dermatome, cranial/sacral localization, and

hemorrhagic lesions. In the majority of

cases, PHN progressively improves and after 1 year only 1–2% of the patients

still experience pain.

The quality of pain associated with herpes zoster varies,

but three basic types of pain have been

described: the constant, monotonous pain (described as

“burning, deep aching, or throbbing”), intermittent pain (“stabbing, shooting”,

lancinating (neuritic)), and/or stimulus-evoked pain. The latter is usually

allodynia (pain with normal nonpainful stimuli such as light touch) or

hyperalgesia (severe pain produced by a stimulus normally producing mild pain).

Allodynia is a particularly disabling component of the disease that is present

in approximately 90% of patients with PHN. Patients with allodynia may suffer

severe pain after even the lightest touch of the affected skin by things as

trivial as a breeze or a piece of clothing. These subtypes of pain may produce

disordered sleep, depression, anorexia, weight loss, chronic fatigue, and

social isolation, and they often interfere with dressing, bathing, general

activity, traveling, shopping, cooking, and housework. The character and

quality of acute zoster pain are identical to the pain that persists after the

skin lesions have healed, although they are mediated by different mechanisms.

Herpes zoster can be

more severe and extensive, with disseminated and/or confluent involvement of

the skin. Patients at risk of severe HZ and hence at increased risk for

cutaneous and/or systemic dissemination as well as more severe PHN can be

identified by a series of risk factors, such as age older than 50 years,

moderate to severe prodromal or acute pain, immunosuppression including cancer,

haemopathies, HIV infected, solid organ and bone marrow transplant recipients,

and other patients receiving immunosuppressive therapies. Certain clinical

findings at an early stage of HZ identify patients at higher risk of

complications. These include the presence of satellite lesions (aberrant

vesicles), severe rash and/or involvement of multiple dermatomes or

multi segmental HZ, simultaneous presence of lesions in different developmental

stages, altered general status, and meningeal or other neurological signs and

symptoms. So it is recommended to search for these signs in patients presenting

with HZ.

Disease

course and prognosis

The total duration of the eruption depends on

three factors: patient age, severity of eruption, and presence of underlying

immunosuppression. The pain and the constitutional symptoms subside gradually

as the eruption disappears. In uncomplicated cases recovery is complete in 2–3

weeks in children and young adults, and 3–4 weeks in older patients. The elderly or

debilitated patients may have a prolonged and difficult course. For these

patient populations, the eruption is typically more extensive and inflammatory,

occasionally resulting in hemorrhagic blisters, skin necrosis, secondary

bacterial infection, or extensive scarring, which is sometimes hypertrophic or

keloidal.

Diagnosis of Herpes

Zoster

In the preeruptive stage, the prodromal pain of herpes

zoster is often confused with other causes of localized pain. Once the eruption

appears, the character and dermatomal location of the rash, coupled with

dermatomal pain or other sensory abnormalities, usually makes the diagnosis

obvious.

A cluster of vesicles, particularly near the mouth or

genitals, may represent herpes zoster, but it may also be recurrent HSV

infection. Zosteriform herpes simplex is often impossible to distinguish from

herpes zoster on clinical grounds. A history of multiple recurrences at the

same site is common in herpes simplex but does not occur in herpes zoster in

the absence of profound and clinically obvious immune deficiency.

Where the diagnosis is uncertain,

confirmation is made by culture or PCR as in chickenpox.

Treatment of Herpes

Zoster

Shingles is a self‐limiting

infection but it is painful, and carries a risk of secondary infection and post‐herpetic neuralgia. Middle-aged and elderly patients with

herpes zoster are urged to restrict their physical activities or even stay home

in bed for a few days. Bed rest may be of paramount importance in the

prevention of neuralgia. Younger patients may usually continue with their

customary activities.

Rest and analgesics are sufficient

for mild attacks of zoster in the young. Higher strength analgesia is often

needed in older patients. Soothing topical preparations with dressings as

blisters break can relieve discomfort. Simple local application of gentle

pressure with the hand or with an abdominal binder often gives great relief of

pain.

Topical Therapy

During the acute

phase of herpes zoster, the application of cool compresses, calamine lotion,

cornstarch, or baking soda may help to

alleviate local symptoms and hasten the drying of vesicular lesions. Cool tap water can be used in a wet compress. The

compresses, applied for 20 minutes several times a day, macerate the vesicles,

remove serum and crust, and suppress bacterial growth. A whirlpool with

Betadine (povidone-iodine) solution is particularly helpful in removing the

crust and serum that occur with extensive eruptions in the elderly. Occlusive

ointments should be avoided, and creams or lotions containing glucocorticoids

should not be used. Bacterial superinfection of local lesions is uncommon and

should be treated with warm soaks; bacterial cellulitis requires systemic

antibiotic therapy. Topical treatment with antiviral agents is not effective.

Antiviral Therapy

Antiviral therapy is the cornerstone in the management of

herpes zoster. The major goals of therapy in patients with herpes zoster are to

(1) limit the extent, duration, and severity of pain and rash in the primary

dermatome; (2) prevent disease elsewhere; and (3) prevent PHN.

Indications for Antiviral

Treatment in Patients with Herpes Zoster

1.

Age

≥50 years

2.

Moderate

or severe pain

3.

Severe

rash

4.

Facial

zoster

5.

Other

complications of herpes zoster

6.

Immunocompromised

state

Normal Patients

Treatment

should be started as early as possible, preferably within 72

hours of the development of skin lesions is optimal, but initiation up to 7

days after onset also appears to be beneficial. The virus is less sensitive to aciclovir in vitro

than HSV and higher doses are recommended. Acyclovir 800 mg five times a day, valaciclovir

1 g or famciclovir 500 mg three times a day for 7 days are

all FDA-approved for the treatment of herpes zoster in immunocompetent

individuals. Treatment leads to more rapid resolution of the skin lesions and,

most importantly, substantially decreases the severity and duration of zoster-associated

pain. Valacyclovir and famciclovir are

as effective as or superior to acyclovir, probably because of better absorption

and higher and more reliable blood levels of antiviral activity are achieved.

They are as safe as acyclovir. If not contraindicated, they are preferable to

acyclovir for oral treatment of herpes zoster. Side- by- side trials have

demonstrated valacyclovir and famciclovir to be of similar efficacy, but one

study from japan showed famciclovir to result in more rapid reduction in acute

zoster pain.

Valacyclovir and famciclovir must be dose adjusted in

patients with renal impairment. In an elderly patient, if the renal status is

unknown, these agents may be started at twice a day dosing (which is almost as

effective), pending evaluation of renal function, or acyclovir can be used. For

patients with renal failure (creatinine clearance of less than 25 mL/min),

acyclovir is preferable.

There

is debate regarding the effect of antiviral treatment in reducing the risk of post‐herpetic neuralgia. In immunocompetent individuals >50 years

of age with acute herpes zoster, famciclovir and valacyclovir are equally

effective (and similar or superior to acyclovir) at reducing the frequency and

duration of postherpetic neuralgia if

started early in shingles.

Because of the lower

risk of PHN, antiviral therapy is less valuable or necessary for treatment of

uncomplicated herpes zoster in healthy people younger than 50 years of age. The

utility of antiviral agents is unproven if treatment is initiated more than 72

hours after rash onset. Nevertheless, it is prudent to initiate antiviral

therapy even if more than 72 hours have elapsed after rash onset in patients

who have herpes zoster involving cranial nerves (e.g., ophthalmic zoster) or

who continue to have new vesicle formation.

Antiviral Treatment of Herpes Zoster in the Normal and

Immunocompromised Host

|

Patient Group |

Regimen |

|

Normal |

|

|

Age <50 years |

Symptomatic treatment alone, or Famciclovir

500 mg PO every 8 h for 7 days or Valacyclovir 1

g PO every 8 h for 7 days or Acyclovir

800 mg PO 5 times a day for 7 days a |

|

Age ≥50 years, and patients of any age with cranial

nerve involvement (e.g., ophthalmic zoster) |

Famciclovir

500 mg PO every 8 h for 7 days or Valacyclovir 1

g PO every 8 h for 7 days of Acyclovir

800 –mg PO 5 times a day for 7 days* |

|

Immunocompromised |

|

|

Mild compromise, including HIV-1 infection |

Famciclovir

500 mg PO every 8 h for 7–10 days or Valacyclovir 1

g PO every 8 h for 7–10 days or Acyclovir

800 mg PO 5 times a day for 7–10 days* |

|

Severe compromise |

Acyclovir

10 mg/kg IV every 8 h for 7–10 days |

|

Acyclovir resistant (e.g., advanced AIDS) |

Foscarnet

40 mg/kg IV every 8 h until healed |

* Famciclovir

or valacyclovir

are preferred because their greater and more reliable oral bioavailability

result in higher blood levels of antiviral activity, the lower susceptibility

of VZV (compared to HSV), and the existence of barriers to the entry of

antiviral agents into tissues that are sites of VZV replication.

Immunocompromised

Patients

In the

immunosuppressed patient, an antiviral agent should always be given because of

the increased risk of dissemination and zoster associated complications. In

patients with mild immunocompromise and localized herpes zoster, oral

acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir will usually suffice.

In severe immunocompromised

patients as well as those with ophthalmic zoster, disseminated zoster, or

Ramsay Hunt syndrome, and in patients failing oral therapy, intravenous

acyclovir should be used at a dose of 10 mg/kg 8‐hourly, adjusted for

renal function. Courses of 5, 7 and 10 days have been used and some advocate a

change from intravenous to oral drug after 48 h. Acyclovir accelerated the rate

of clearance of virus from vesicles and halted progression of the disease and

markedly reduced the incidence of visceral and progressive cutaneous

dissemination.

Treating acute zoster pain

Greater

severity of acute pain is a risk factor for PHN, and acute pain may contribute

to central sensitization and the genesis of chronic pain. Therefore, aggressive

pain control is both reasonable and humane. The choice, dosage, and schedule of

drugs are governed by the patient's pain severity, underlying conditions, and

response to specific drugs. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or

acetaminophen treat mild pain. Opioids, such as tramadol, treat moderate to

severe pain. Add gabapentin if needed. Tricyclic antidepressants can be used

when opioids are insufficient. If pain control remains inadequate, regional or

local anesthetic nerve blocks should be considered for acute pain control.

Treatment of Postherpetic Neuralgia

Once

established, PHN is difficult to treat. Despite the vast array of medication

options, PHN is commonly difficult to treat for two reasons. The recommended

medications are simply often not effective. Second, in the elderly who are most

severely affected by PHN, these medications have significant and often

intolerable side effects, limiting the dose one can prescribe. If multiple

agents are combined to reduce the toxicity of any one agent, the side effects

of these agents overlap (sedation, depression, and constipation) and there may

be drug–drug interactions, limiting combination treatment options. Fortunately,

it resolves spontaneously in most patients, although this often requires

several months.

The

following drugs are effective for pain relief in PHN: gabapentin, pregabalin, tricyclic

antidepressants (TCAs), tramadol, lidocaine patch 5%, and

high-concentration 8% capsaicin patch. The choice of

these medications should be guided by the adverse event profiles, potential for

drug interactions, and patient comorbidities and treatment preferences.

Topical Therapy

Topical anesthesia delivered by means of a 5% lidocaine

patch has been shown to produce significant pain relief in patients with PHN.

The 10 × 14-cm lidocaine patch contains 5% lidocaine base, adhesive, and other

ingredients on a polyester backing. It is easy to use and is not associated

with systemic lidocaine toxicity. Up to three patches are applied over the

affected area for 12 hours a day. The disadvantages of the patch are

application site reactions, such as skin redness or rash, and substantial cost.

Eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) cream applied once a day over the

affected area under an occlusive dressing is an alternative method of

delivering topical anesthesia.

A single 1-hour application of a high-concentration capsaicin

patch (8%) significantly reduces pain from PHN from the second week after the

capsaicin application throughout a subsequent 12-week period. The high-concentration

patch is generally well tolerated. Adverse events include increases in pain

associated with patch application (usually transient) and application-site

reactions (e.g., erythema). The role of the high-concentration capsaicin patch

in the treatment of PHN is yet to be clearly established, partly because its

long-term benefits are not yet known. However, this intervention has promise

because a single 1-hour application may yield several weeks of pain reduction.

Oral Agents

Three classes of oral medication are used as standards to

manage PHN—tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), antiseizure medications, and long

acting opiates.

Opiate analgesics

If opiate analgesia is required, it should be provided by

a long acting agent, and the duration of treatment should be limited and the

patient transitioned to another class of agent. Constipation is a major side

effect in the elderly. During painful zoster these patients ingest less fluid

and fiber, enhancing the constipating effects of the opiates. Bulk laxatives

should be recommended. Tramadol is an option for acute pain control, but drug

interactions with the TCAs must be monitored.

Controlled-release oxycodone (10

mg every 12 hours) is an effective analgesic for the management of steady pain,

paroxysmal spontaneous pain, and allodynia. The dose is increased weekly up to

a maximum of 30 mg every 12 hours. Others have found narcotics ineffective for

the long-term control of pain from PHN and to be associated with unacceptable

side effects. The most common side effects are constipation, nausea, and

sedation.

Gabapentin and Pregabalin

These

anticonvulsant drugs are effective in the treatment of pain and sleep

interference associated with PHN. They are FDA approved for the treatment of

post herpetic neuralgia. Mood and quality of life also improve.

Gabapentin has been shown to

produce moderate or greater pain relief in patients with PHN. Gabapentin is

started as a single 300-mg dose on day #1, 600 mg/day on day 2 (two 300-mg

doses), and 900 mg/day on day 3 (three 300-mg doses). The dose can

subsequently be titrated up as needed for pain relief to a daily dose of 1800

mg (three 600-mg doses per day). A minimum of total dose of 600 mg or more is

needed to obtain optimal benefit.

Additional benefit of using doses greater than 1800 mg/day has not

demonstrated. Frequent adverse effects of gabapentin include somnolence,

dizziness, and peripheral edema.

Pregabalin has been shown to

produce 50% or greater pain relief in 50% of patients with PHN. Pregabalin has

improved pharmacokinetics and is dosed at 300 mg or 600 mg daily, depending on

renal function, with better absorption and steadier blood levels. It is

administered in two or three divided doses per day. Begin dosing at 150 mg/day;

dosing may be increased to 300 mg/day within 1 week. Maximum dose is 600

mg/day. Dizziness, somnolence, and peripheral edema are also the most common

adverse effects reported for pregabalin. Pregabalin has a less complicated dose

titration schedule and a faster onset of action than gabapentin.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Low-dose tricyclic antidepressants have

demonstrated considerable efficacy and appear to act by a mechanism independent

from their antidepressant effects (because relief of PHN

occurs at less than antidepressant dosages).

They are particularly useful for patients with hyperesthesia and

constant burning pain. Nortriptyline and

desipramine are

preferred alternatives to amitriptyline

because they cause fewer cardiac adverse effects, sedation, cognitive

impairment, orthostatic hypotension, and constipation in the elderly.

Nortriptyline is a noradrenergic metabolite of amitriptyline. Pain relief occurs

without an antidepressant effect with nortriptyline, and there are fewer side

effects with nortriptyline. Therefore nortriptyline is the preferred

antidepressant, although desipramine may be used if the patient experiences

unacceptable sedation from nortriptyline. For best results, nortriptyline

should be given early in a dose of 25 mg daily and continued for 3–6 months.

These adrenergically active antidepressants may be most effective

if antiviral treatment is given during the acute attack of shingles.

Side effects

include confusion, urinary retention, postural hypotension, and arrhythmias.

Dry mouth occurs in up to 25% of patients with nortriptyline. Constipation,

sweating, dizziness, disturbed vision, and drowsiness occur in up to 15% of

patients with nortriptyline. Use tricyclic antidepressants with caution in

patients with cardiovascular disease, glaucoma, urinary retention, and

autonomic neuropathy. Screen patients older than age 40 for cardiac conduction

abnormalities.

Combination therapy with gabapentin and nortriptyline

produces greater pain relief than either agent alone. The most common adverse

event is dry mouth secondary to nortriptyline. These results suggest that

combination therapy may benefit some individuals with PHN who have responded to

one of the agents chosen, but at the risk of increased adverse effects than

with either drug alone.

If the patient

fails to respond to local measures, oral analgesics, including opiates, TCAs,

gabapentin and pregabalin, referral to a pain center is recommended.

Emotional support

Patients

with PHN can be miserable for several months. Emotional support is another important

therapeutic measure.

Therapeutic ladder of herpes zoster

First line

·

Aciclovir

·

Valaciclovir

·

Famciclovir

Second line

·

Aciclovir, iv

Third line

·

For post‐herpetic neuralgia:

·

Nortriptyline

·

Desipramine

·

Gabapentin

·

Pregabalin

Medications

Commonly Used for Treatment of Pain Associated with PHN

|

Medication |

Dose |

Dose

adjustment |

Maximum

dose |

Side

effects |

|

OPIOID AND NONOPIOID ANALGESICS |

||||

|

Tramadol |

50 mg once or twice daily |

Increase by 50-100 mg daily in divided doses every 2

days as tolerated |

400 mg daily; 300 mg daily if patient is >75 years

old |

Drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, nausea, vomiting |

|

ANTICONVULSANTS |

||||

|

Gabapentin |

300 mg at bedtime or 100-300 mg three times daily |

Increase by 100-300 mg three times daily every 2 days

as tolerated |

3600 mg daily |

Drowsiness, dizziness, ataxia, peripheral edema |

|

Pregabalin |

75 mg at bedtime or 75 mg twice daily |

Increase by 75 mg twice daily every 3 days as tolerated |

600 mg daily |

Drowsiness, dizziness, ataxia, peripheral edema |

|

|

||||

|

Nortriptyline |

25 mg at bedtime |

Increase by 25 mg daily every 2-3 days as tolerated |

150 mg daily |

Drowsiness, dry mouth, blurred vision, weight gain,

urinary retention |

|

TOPICAL THERAPY |

||||

|

Lidocaine patch (5%) |

One patch, applied to intact skin only, for up to 12 hr

per day |

None |

One patch for up to 12 hr per day |

Local irritation, if systemic, absorption can cause

drowsiness, dizziness |

Prevention

of postherpetic neuralgia

Very large

randomized placebo-controlled trials of the zoster vaccine in adults older than

60 years revealed a significant reduction in PHN in people who received the

vaccine.

The use of

gabapentin combined with valacyclovir during acute herpes zoster is more

effective in preventing post herpetic neuralgia than treatment with valacyclovir

alone, particularly in patients at highest risk for PHN. So this regimen is

recommended for patients with acute herpes zoster presenting with moderate to

severe pain.

Prevention

of herpes zoster

In later life, immunity against VZV wanes, but can be

boosted by vaccination, that can prevent or reduce the severity of herpes

zoster and its complications, including postherpetic neuralgia. The zoster

vaccine is the same as the varicella vaccine but at a higher virus titer. FDA

approved this live attenuated vaccine (Zostavax®) for

adult ≥50 years of age in 2006. The Advisory Committee on Immunization

Practices (ACIP) recommends a single dose for all immunocompetent individuals’

≥60 years of age, whether or not they have a history of varicella or herpes

zoster. Older adults who have a current episode of herpes zoster may ask to be

vaccinated, but zoster vaccination is not indicated to treat acute herpes

zoster or PHN. The optimal time to immunize an individual after a recent

episode of herpes zoster is unknown, but it is believed that an interval of 3–5

years after the onset of a well-documented case of herpes zoster is reasonable.

A history of

anaphylactic reaction to any of the vaccine components is a contraindication to

the vaccine. The zoster vaccine should not be given

to persons who have severe acute illness, including active untreated

tuberculosis, until the illness has subsided. Persons with leukemia, lymphomas,

or other malignant neoplasm affecting the bone marrow or lymphatic system, or

with AIDS or other clinical manifestations of HIV infection, including those

with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts ≤200 per mm3 and/or ≤15% of total lymphocytes

should not receive zoster vaccine. Persons on immunosuppressive therapy,

including high-dose corticosteroid therapy, should not receive the vaccine. The

ACIP defines high-dose corticosteroids as 20 mg or more per day of oral prednisone or equivalent for 14

days or more. Low doses of methotrexate (≤0.4 mg/kg/week), azathioprine (≤3.0 mg/kg/day), or

(prednisolone ≤20 mg/day) are not considered to have significant

immunosuppression. The vaccine is also contraindicated in patients receiving

biological therapies but may be given after 3–6 months following discontinuation

of the immune suppression. The use of heat‐treated VZV vaccine,

currently under investigation, may be a safer option in these situations.

When considering the zoster vaccine,

older adults may express concerns about transmission of vaccine virus to other

individuals. Transmission of VZV requires the development of a vesicular rash

containing vaccine virus after vaccination. If there is no rash, there is no

transmission. Zoster vaccine-associated vesicular rashes are very unusual.

Although vesicular lesions may appear at the injection site, vaccine virus nor

wild-type VZV were detected by DNA PCR testing in vesicular fluid. Transmission

of vaccine virus from recipients of zoster vaccine to susceptible household

contacts has not been documented. Thus, immunocompetent older adults in contact

with immunosuppressed patients and susceptible pregnant women and infants

should receive zoster vaccine to reduce the risk that they will develop herpes

zoster and transmit wild-type VZV to their susceptible immunosuppressed contact

and pregnant women and infants. In the unlikely event that an immunocompromised

contact develops a significant illness caused by vaccine virus, he/she may be

treated with standard anti-VZV agents (acyclovir, valacyclovir, or

famciclovir).

FDA Approval

of recombinant zoster vaccine

A recombinant subunit vaccine containing VZV glycoprotein E and the AS01B adjuvant system (HZ/su) administered in two

doses two months apart reduced the likelihood of herpes zoster ~97% and

postherpetic neuralgia ~90% in adults ≥50 years of age. Efficacy of this

vaccine was unaffected by advancing age and persisted for >3 years; severe

injection site reactions and systemic symptoms each occurred in ~10% of

patients.

This

recombinant adjuvant vaccine (Shingrix®) was approved by

the FDA in October 2017 for individuals 50 years of age or older for the

prevention of herpes zoster.